WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 190! The Adventures with Technologies of Becoming of the Novel...

Good morning becomings recovering from being “beings”,

We hope you had a wonderful May Day on Thursday – celebrating work and workers from insect laborers, to human workers, to the labor of emergent systems.

This week, the newsletter continues to explore last week's questions of Authorship and Control in creative processes, as well as our now long-standing topic of the logic of Technology. Today, we want to shift the perspective that we utilize to engage with these themes, to engage with our individual first-person experiences in relation to creativity, authorship, and control:

How do we feel in and around our engagements with creative processes?

Our contention is that much of how we feel, act, perceive and experience has to do with what is afforded us (as ways of feeling, sensing/perceiving and acting) because of a historical configuration of practices, concepts, tools and environments that creatively give rise to a novel field of possible actions that we term creativity.

Pardon the interruption: If you enjoy this newsletter, we think you might also enjoy a free event we are hosting May 21st - please accept this as our formal invitation to you:

While all of this can be quite a mouthful, the phrase “afforded us”, which is stuck in the middle of this, can slip by unnoticed.

What is meant by “afforded us”?

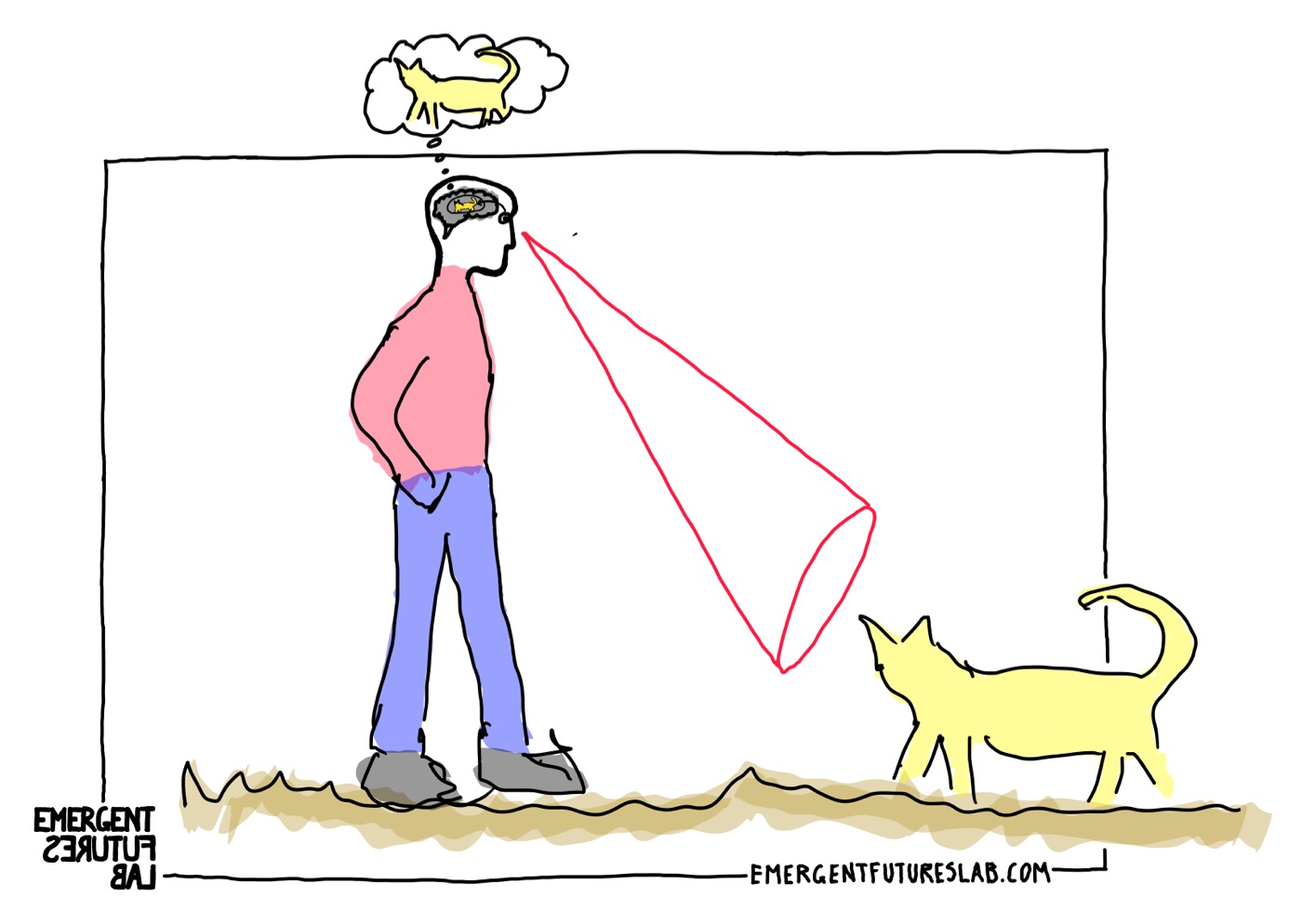

We are referencing the critical concept of “affordances” from the field of Environmental Psychology. This concept was developed by Eleanor and James Gibson to challenge our Cartesian view of perception. The Cartesian view of perception holds that our experiential relation to reality is one of internal subjective perceptions of an external objective world. Another way to put this is that the Cartesian view claims that what we are doing in experience is that we are taking in data of an external world via our senses, and then turning it into an internal representation via brain activities:

But, as Environmental Psychology argues, this view is a mistake. We are far more actively and permanently entangled with the specific world around us that is also actively co-creating our action possibilities for it to be the case that there is a clear dichotomy between our internal subjective perceptions and the world “out there”:

We are always already active beings fully embedded in a specific way of life, directly experiencing reality before anything else as “specific possibilities for action”:

What does this mean? In short: We are not looking out at the world, puzzled by what we perceive. Imagine the absurdity of such a scenario:

“What is this beneath our feet? – is it a walkable surface? Is it a video projection? or is it just colors pressing against the back of my eyes? How should I interpret this sense data?”

No, in the morning, upon waking, we roll out of bed and proceed to stand and walk into the kitchen to make coffee. The relation between our bed and body affords the possibility of rolling-into-standing, and the relation between our bodies and the carpet affords the possibility of standing and walking. Our experience and action is not a three-step process of: (1) explicit conscious knowledge and carefully parsed recognition that then (2) leads to a rational reflective decision to move, and finally (3) we perform an action:

“Oh, I see that I am in a bed, and upon careful investigation of my memories, I recognize that there is the floor and I can now carry out a rolling procedure to stand up…”

Rather, before any explicit reflective thought, we are already in action, flowing in active experience: sensing, feeling, intuiting, in acting. And the more explicit forms of reflexive representational knowing (know-what) build upon this direct enactive experiential “know-how.”

So, what is an affordance? Is it just a fancy word for the agency of and in objects? Does the coffee cup handle “afford” us the possibility of grasping? No. The concept of affordances critiques both the Cartesian concept of the self as interacting with an external world via internal representation and a view of things (technologies) as possessing internal properties (e.g., the cup handle possesses “graspability”).

Affordances are not the property of things, nor are they an internal property of “us”. An affordance is neither “out there” nor is it merely “in us”. The affordance of the carpet being “walkable” is a relational property that has to do with the kind of bodies we have, the types of actions we engage in, and the configuration of the environment:

Thus, what we sense and experience directly as the world is a relation (what we termed in last week's newsletter as “the middle”). This is worth repeating:

What we sense and experience directly as the world is a relation.

This direct relational experience is something upon which complex social engagement comes to develop into something more abstract: the concept “the carpet,” for example, which we can define from a third-person perspective and discuss abstractly (what can be called “know what”), is derivative of that direct active relational experience.

The danger in understanding affordances is that we can imagine it is something happening to us. One could fall into a way of thinking – now I have no choice – the configuration out there is imposing on me a false choice between a series of pre-determined possible actions that I must choose. But – what is critical to keep in mind: this is not happening to us. The field of possibilities for action is not being imposed upon us by some thing (the relation) wholly separate and external to us and our actions. We are not passive bystanders. We are active, embodied participants (who are also shaped by a history) in the ongoing making of this configuration. But it is also true that we are not in charge. We cannot conjure up possibilities for action – affordances – at will. Agency (the ability to effect and be effected) is relational between us. But like a dance or surfing, it is a very active, mutually co-determining creative play without beginning or end.

The relation dance extends in all directions: the “us” that shows up does not begin with us – we are not the emanations of some deep internal ahistorical “self”. We show up as an embodied being shaped and transformed physically and psychically by embedded and extended practices, habits, and tools. We are always already in and of a way of life (a specific world).

Of course, we could think of all of this as just things “added” to, and supplementing our true, unchanging inner self and its relation to an objective and given external world. But this is a situation where the complex interactions act in non-linear ways, where small additions can have a disproportionate and entirely qualitatively transformative effect. Think of wine – it is not grape juice with just the smallest addition of yeast. The interactions of the grape juice with the very smallest amount of yeast are qualitatively transformative of the whole. Wine in its temporal process contains grape juice, but it is not merely a supplemented grape juice.

Our tools, habits, embodied practices, and specific environments are no mere addition that flavors our essential and ultimately unchanging self.

We say of such relational emergent situations that they are non-decomposable, non-additive, and non-proportional:

The addition of yeast is, for example, “non-decomposable” – you cannot take it apart once the transformation to wine has happened. And it is also “Non-Additive”-- which is to say, adding yeast is not to quantitatively transform grape juice; rather, it is qualitatively transformed. And finally, these transformations are not reliant on the size of what is added – they are “Non-Proportional”. One does not need to add a massive amount of anything to get a radical transformation – the smallest amount of yeast will do.

Now, all of this is equally true of our behavior and experience. Changing the configuration via the addition of something small but transformative will fundamentally qualitatively change who we are at every level and in every aspect. It is a World Changing adjustment to the configuration.

Agency is arising (emerging) from the middle. Control is arising (emerging) from the middle. And we, as conditioned co-creative beings, experience this middle as “affordances” – the immediate experience of possibilities for action, which is simply our shared reality.

We change our ecosystemic reality, and what arises as our immediate experience is happening not by a debate of ideas (know-what) but by changing our embodied routines and habits, in relation to changing our tools, practices, concepts, and environments (emergent know-what). This is what is often called “scaffolding”:

“We are [embodied] social environment-altering tool users. Tools give us new abilities, leading us to perceive new affordances, which can generate new environmental (and social) structures, which can, in turn, lead to the development of new skills and new tools, that through a process… of scaffolding greatly increases the reach and variety of our cognitive and behavioral capacities” (Micheal Anderson)

But the term scaffolding can make it seem like this is also something extra, and as something extra, it is inessential and removable – that we can simply plug out of and into other scaffolds. But this way of thinking misses the Non-Decomposible logic of configurations. These transformations are irreversible. We can change things – but only by going forward from where we are. There is no dismantling of one set of scaffolds and resetting.

Why is it that we just don’t perceive reality from our own personal subjective stance? Why isn’t cognition about “transposing a world of predefined significance into the inside of an agent”? (Di Paolo et al, Linguistic Bodies):

Well, for one, neither the world nor the agent is static or neutral – significance is an achievement of engagements under precarious dynamic conditions. We, as agents, are collectively (in collaboration with an active environment) actively co-configuring our world into semi-stable relation-dominant patterns and propensities.

We have to acknowledge that much of the agency and control that we imagine that we have is actually the emergent agency of the configuration. The configurational process that gives rise to a field of possibilities is what we termed last week, Abstract Machines:

Abstract Machines:

With an Abstract Machine, no one is in control, no one is guiding things – once a set of conditions comes into stable existence (a stable “configuration” emerges), a particular process is set in motion. This process could be evolution, but is also the configurations that give rise to: plate tectonics, capitalism, household behaviors, the digestive process, driving practices emerging from traffic circles, dining room conversations – or in our case a historical and situated way of sensing, feeling, intuiting, understanding and practicing creativity…

So, what does an understanding of our direct primary experience of reality as “affordances” emerging from “configurations” have to do with contemporary creativity practices?

Consider for a moment what psychic and physical patterns this question triggers in you:

“I would like you to do something creative – What would you like to do?”

How does this make you feel? What affordance routines in thinking, feeling, and action does it trigger in you?

What are the habits, practices, tools, and environments that you are drawn towards engaging?

Perhaps you remember childhood experiences. Or some other time you were challenged to respond to a similar question?

Perhaps you have drawn since you were young and have a deeply embodied set of skills around drawings that afford you possibilities of diagramming, drawing, and visualizing? Do you think of an art practice?

Or you have always written and enjoy writing – does this afford you ideas for a novel, a piece of music, or a poem?

Are you drawn to the affordances of discussing – what we might term as the general practices, tools, and environments of “brainstorming”?

Or perhaps because of your deep engagement with current affairs, you are drawn to an explicit problem that should be addressed and solved?

Perhaps you think – “I’m not that creative! Why are you asking me?”

It is worth pausing on reading this and considering what you would do, and what immediately comes to mind. We would invite you to make notes – write some of this down. Importantly, don’t overthink things. The question is “what immediately comes to mind – what are you immediately pulled towards doing?”

So, what do we sense as the next steps? What practices, senses of self, and habits arise?

Whatever these are (and we will get to the what in a moment), all of these follow a diverse and specific set of “possibilities for action” (affordances) within the context of our way of life with its habits, practices, concepts, and environments. There is a general, historically conditioned ecological shape to all of this.

So, what is the conceptual logic and pattern that emerges from our contemporary configurations in regards to creative practices? What emerged for you in answering this question:

“If we asked you to do something creative, what would you do?”

Our contention is that our spontaneous answers to this question would follow a general, recognizable pattern of affordances (possibilities for action) that have emerged from our historically developed configuration of deeply embodied habits, practices, tools, concepts, and environments.

So, what is the general recognizable pattern that our contemporary creativity practices take on?

Now, just to contextify what follows – we have not come to these conclusions lightly, or without research. Years ago, Jason and I did an extensive review of Innovation methods, definitions of creativity, researched students in creative fields and their responses, as well as consulted major surveys and online databases of innovation methodologies. What we concluded is what is also in line with the anthropologists of Western models of production, such as Philippe Descola, Mary Strathern, and Marshall Sahlins have concluded: there is a general pattern to the contemporary Western approach to creation and creativity. This configuration and its affordance propensities are what Philippe Descola in Beyond Nature and Culture termed: the “Heroic Model of Creativity”.

The anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, in writing an introduction to Beyond Nature and Culture, says this of the Heroic Model of Creation:

that it fundamentally involves “the imposition of form upon inert matter by an autonomous subject… who commands the process by a pre-established plan & purpose”.

The first thing to say about this is what it is not:

It is not a discreet concept or ideology that some of us have been “duped” into buying into.

Despite Descola’s title, it is best not to see it as a model at all. That would divorce it from the configuration that gives rise to it and ultimately give it a far too independent character. Rather, it is the emergent conceptual outcome of configuration (a technology – or an Abstract Machine) that most of us, who have co-evolved with Far West-Asian assemblages of creativity-related concepts, practices, and environments, have been involved in co-creating and have been co-created by. It is not an abstraction separate from and imposed upon us from the outside (an ideology). Rather than being a free-floating model or ideology living in the aether, it is immanent.

What appears as the emergent conceptual logic of some set of practices is often assumed to underpin and be the source of the practices. This is true of the Heroic Model of Creation. We mistakenly take it as the cause of a certain approach to creativity.

Think of the many discussions where it is claimed that some “mindset” causes such-and-such an outcome ( for example, that “patriarchy”, or “human greed”, or “heroic creativity” leads to certain practices).

But the conceptual logic (e.g., “heroic creativity”) is not something other than and in addition to the component processes and their emergent relational configuration. The logic of heroic creativity is immanent to the relational configuration, not something in addition to it. It is the configuration that guides the configuration. We mistakenly give the conceptual logic causal authorship and agency – we make it a thing that is both before and above the outcome, when in actuality it is nothing more than the outcome of the relations themselves, and it is not anything wholly separate from it. (The iceberg model is exploratory of this mistake – see above.)

While the immanent reality is quite different, the philosopher John Searle wrote a really interesting paper, “Consciousness, Free Action, and the Brain,” on the topic of free will. In it, he makes several powerful observations and arguments about the assumptions of singular causal sources and their relation to emergent systems.

He argues that to see this conceptual logic as a “more-than” that either underpins or rests upon the surface (like paint on a table) is the problem: “All of this is wrong… — emergent conceptual qualities are “no more on the surface of [things] than liquidity is on the surface of water”.

An emergent quality or feature is rather a feature of the whole system, “and is present — literally — at all of the relevant places of the system in the same way that the water in the glass is liquid throughout… the whole system moves in a way that is causal.”

The Heroic Model of Creativity, like liquidness, is immanent to and present throughout the configurational system.

Speaking very generally, we have emerged into our own sense of individual creative agency within a historical configuration of relational practices and environments (which we participate in co-shaping) – and what their ever-evolving stream and emergent immanent logic affords us as ways of seeing, sensing, feeling, thinking, and acting. For better or worse – the immanent Heroic Logic of Creativity as an ecology is our mundane, embodied, and enacted reality.

And this is the part we wish to focus on today: That our mundane everyday implicit sense of ourselves, as well as our intuitions, our habits, and embodied and extended routines, are of this configuration and what its emergent logic affords.

(Here we would be curious about how you answered the question – does it, in general, fit with what we are presenting? What this means is that for many, if not most of us (and we include ourselves in this), we fall into a certain set of routines that in very general terms follow the logic that Sahlins outlines as this Heroic Model of Creation. Why do we – Jason, Andrew, and Iain also fall into this? Shouldn’t we know better? Of course, we know creativity is something very different. But knowing is not the issue. Or at the very least, it is not the whole issue. We are also of these configurations.

What this means is that for many, if not most of us (and we include ourselves in this), we fall into a certain set of routines that in very general terms follow the logic that Sahlins outlines as this Heroic Model of Creation. Why do we – Jason, Andrew, and Iain also fall into this? Shouldn’t we know better? Of course, we know creativity is something very different. But knowing is not the issue. Or at the very least, it is not the whole issue. We are also of these configurations.

To acknowledge that we are also of these configurations means, in very practical terms, that while we might be opposed to the ideation-first model of innovation, we evolved in these contexts, and we find ourselves in environments, enmeshed in organizational practices, and utilizing tools that have strong propensities towards ideational affordances. And in engaging with these practices, tools, and environments, they loop through us, shaping our sensibilities, preferences, language, muscle memory, forms of comfort, intuition, and perception on a tacit, immediate experiential level.

Ultimately, it is not about what we think – or at least it is not about what we think alone. It is not about our mindsets. In a very real sense, what we think, feel, sense, and perceive is the outcome of embodied, embedded, extended, and enactive practices. Affordances…

And to radically separate our thinking from this context is a mistake. And what is even a greater mistake is to then put what emerges as ideational concepts from this context (and is immanent to it) as the cause of it. E.g., to say that the Heroic Model causes us to act in a certain manner. We have gotten the order wrong.

Why it is so hard to change has to do with where agency and control are in the complex context of our lives. We need to come to grips with the configurations that we are actively of, their affordances, and immanent emergent conceptual logics.

To understand how this works, we need to come to grips with the logics of emergence, affordances, configurations, abstract machines, enaction, and immanence – as well as the situated historic logic of our specific ecosystems (the ecosystem of the Heroic Approach to Creativity).

None of this is not reducible to a lack of knowledge or understanding alone.

The Immanent Heroic Creative ecosystem, of which we are an active part of, is a profound problem (which we will get into over the next couple of weeks). But the problem is not conceptual – it is not a debate of ideas or a call for a new mindset. The changes necessary are far more complex and far less sexy. We need to work at the level of tools/technologies, embodied habits, specific environments and taskspaces, process logics, configurations, and much else that is far from the glamorous battle of ideas.

Next week, we are going to trace out the specific mundane details of the Heroic Approach to Creativity’s ecosystem and then offer some speculations on possible alternative ecosystems based upon our own experiments.

For now, we would love to hear from you…

Have a great week testing and co-evolving novel configurations

Stay immanent and follow novel differences that might make a qualitative difference.

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.