WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

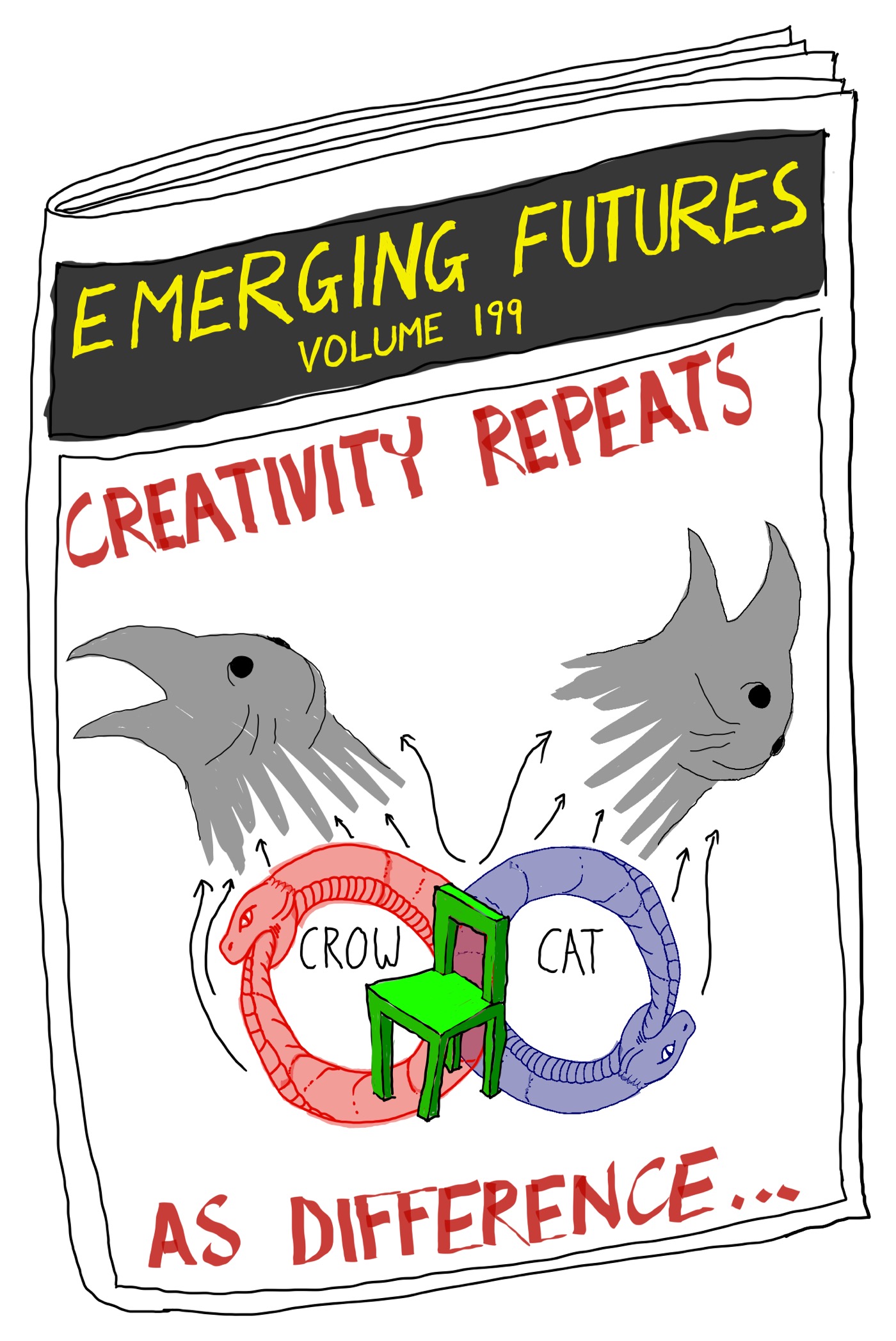

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 199! Creative Activity: The Triple Loops of Time’s Meeting & Making...

Good morning enactive activities of becomings transforming events and selves top-down and bottom-up.

Today is July 4th, a day that marks Ra o te Ui Ariki (the celebration of the traditional leaders) on the Cook Islands, Liberation Day in Rwanda, and Independence Day in a number of countries, including the USA. For us, at Emergent Futures Lab, where the focus is on creativity, we prefer to leapfrog both independence and dependence to celebrate intra-dependence – as all creative processes are intra-dependent ones.

Independence and Dependence – like most things that have been invented via binary oppositions – are systems where both and one or the other alone tend to be false – and irrelevant.

The logic of the prefix “intra” – how something is both in and of another thing has been a hidden theme of our last two newsletters, and pretty much all of our experiments with creative processes.

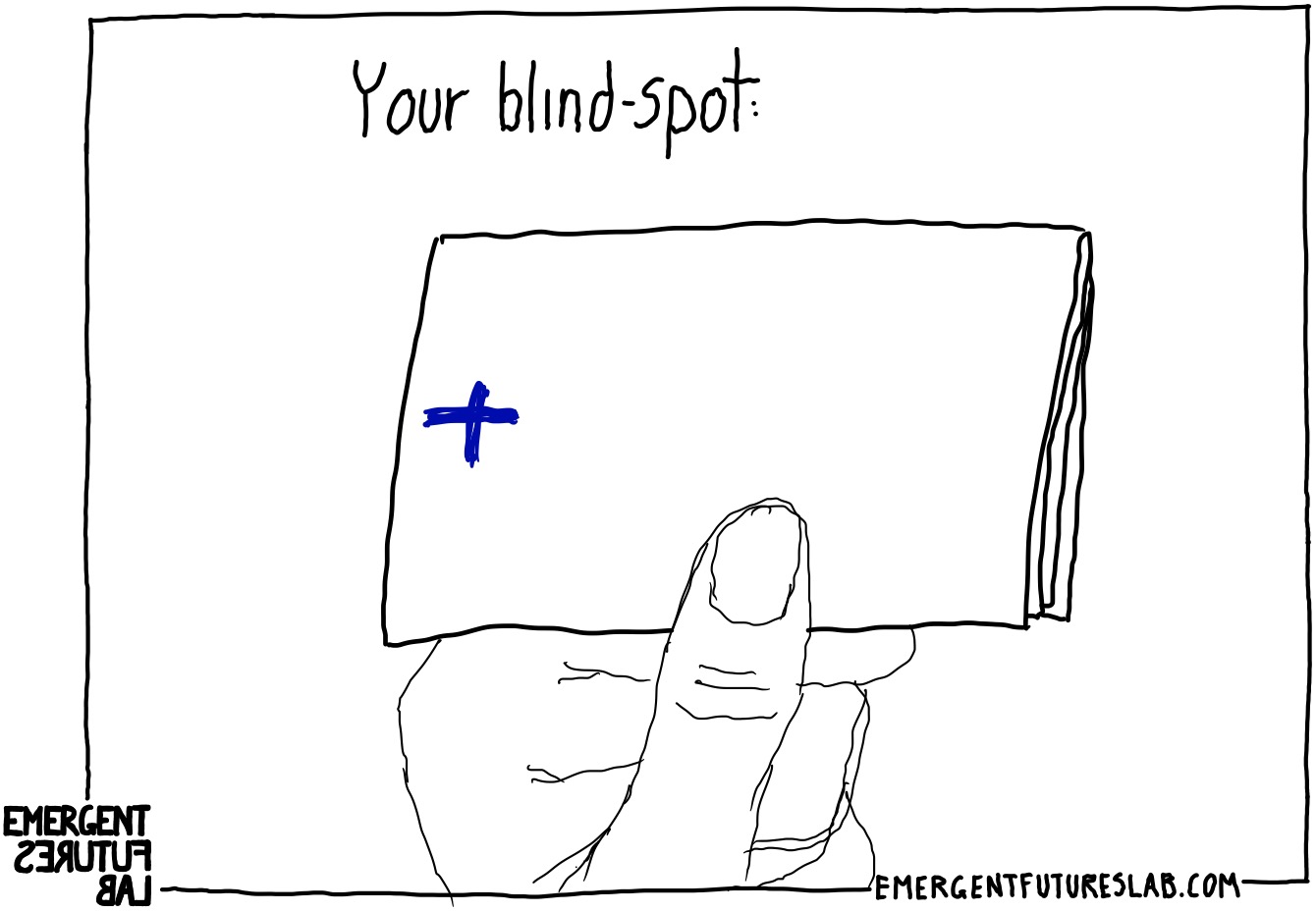

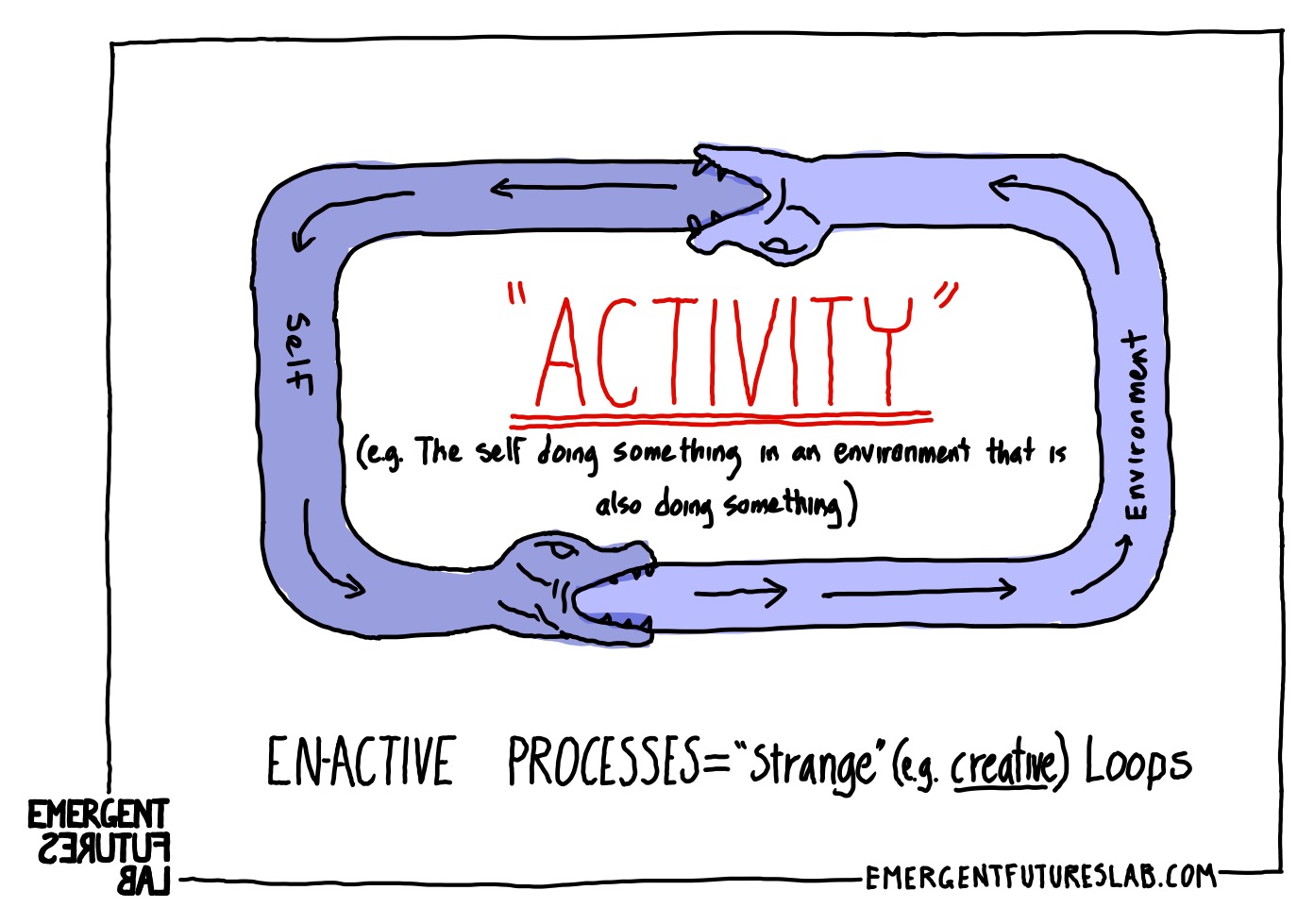

Over the last two weeks ,we have been exploring activity – and more specifically en-action – which is to say how we are in and of activity – that all activity is creatively intra-dependent – and ultimately that activity makes us. And it is this puzzling creative looping quality of activity – that we do not notice – that in fact falls into an “activity blindspot” that we are focused on.

So, then two quick reminders before we move on to some new material:

ONE: A blind spot is what Evan Thompson and his co-authors, Adam Frank and Marcelo Gleiser, in their wonderful book The Blind Spot, define as “something that we don’t see, and we don’t see that we don’t see it.”

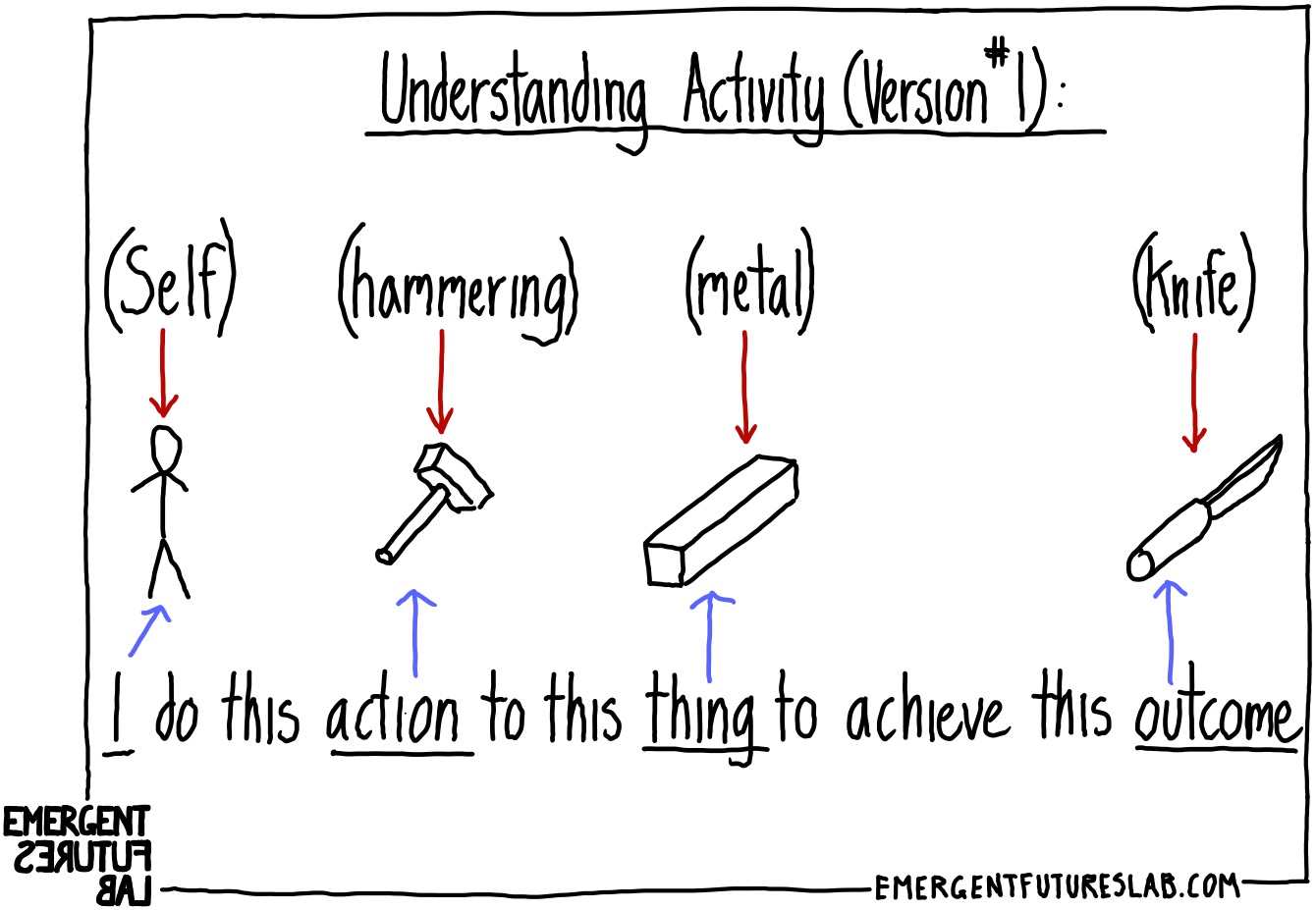

TWO: What is activity? Last week we framed it this way:

“When we are in action, we are not just doing something, such as carry out an action with a tool on an object towards a known end in a passive and neutral manner like that of a robot carrying out a preprogrammed routine:

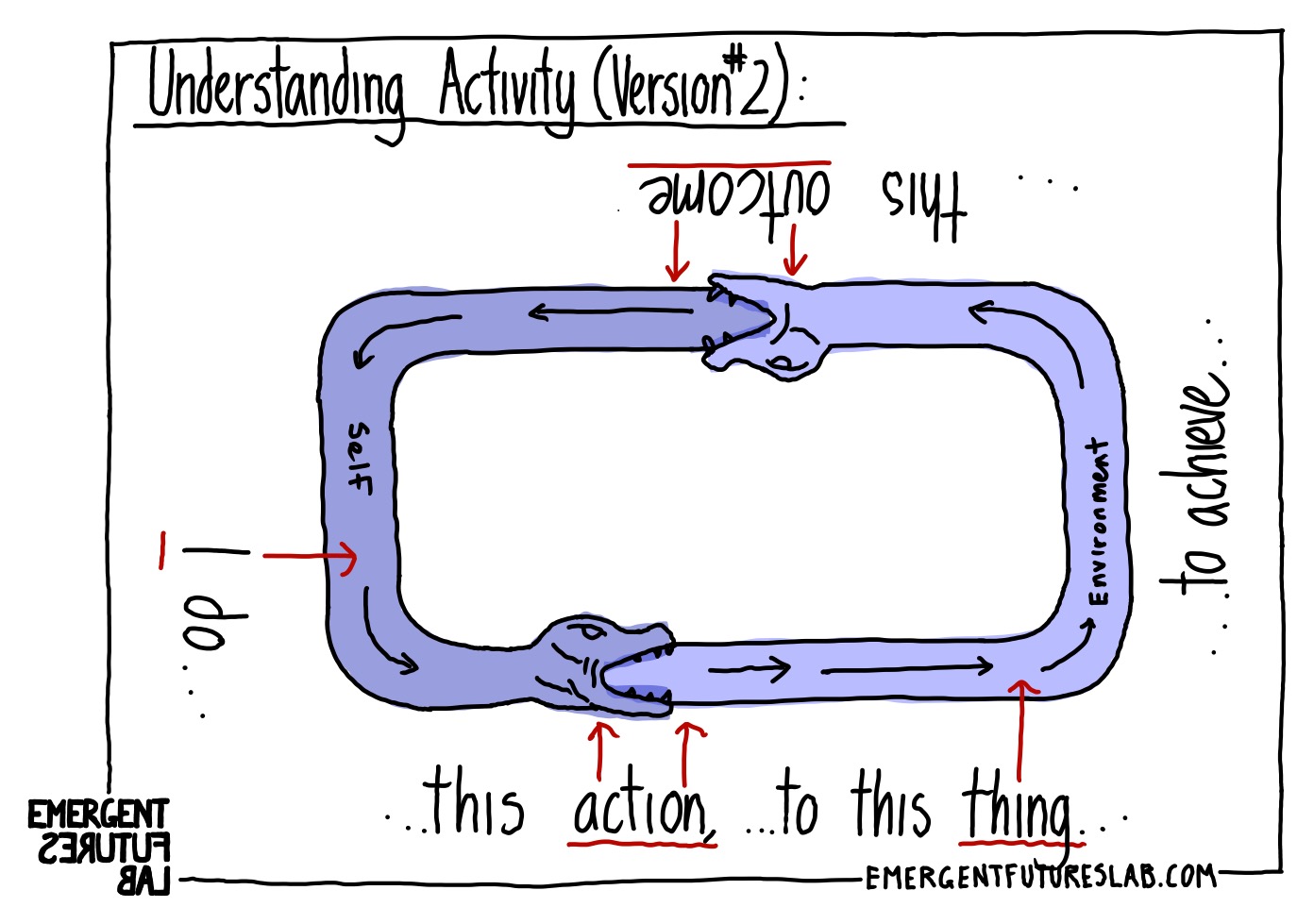

Rather, when we are in action (and this is always the case), the action is also in us and changing us – it is an active loop and not a passive line:

This is why we prefer to use the odd and awkward phrase where possible: “we are of our actions”. To simply say “in” would suggest that we come out of action unchanged – but the activity changes us, the environment, and ultimately the activity itself.

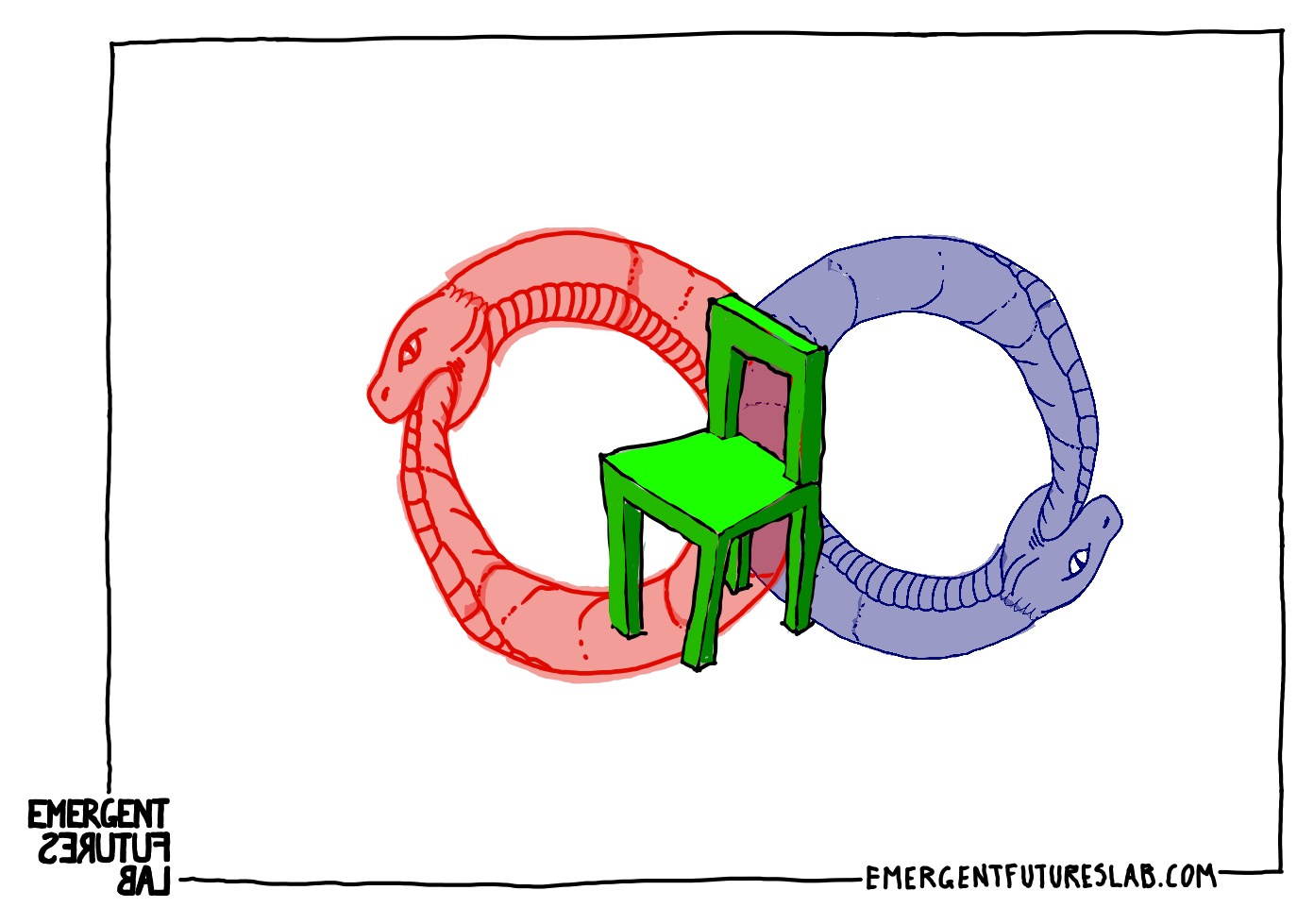

Action has a creative agency, and this is a creativity that is separate and different from our intentional logic in initiating the activity. We cannot stress this enough: Activity has its own unique agency and creativity (which is distinct from the purpose of the activity itself). Action always involves a creative transformative looping that is always there – what we have called elsewhere the “strange loops” – the orobourian loops of the dragon eating its tail):

And it is here we ended last week, but this particular blind spot does not stop there. And this brings us to the second blindspot in activity – our blindness to the activity of world-making.

The looping of originary emergent sense-making has neither a beginning nor an end. We cannot ask about chickens or eggs. Nature or culture. Everything begins and stays in the middle. There are only hyphens: bio-enculturated actions – bio-geo-soci-enculturated actions. And ultimately, all the hyphens disappear in a repeated emergent looping fusing-transforming. We must take great care not to artificially pull apart what cannot be decomposed.

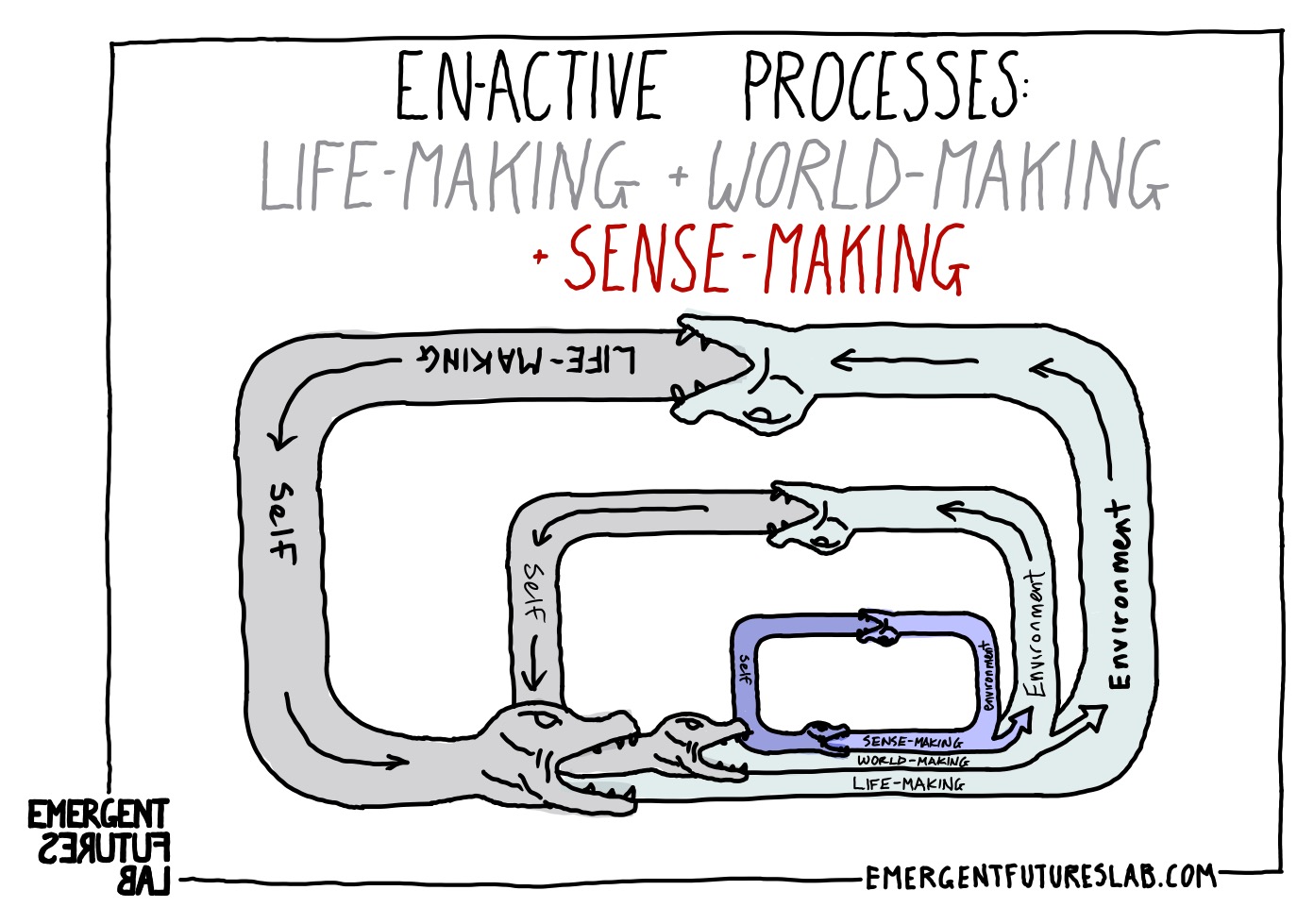

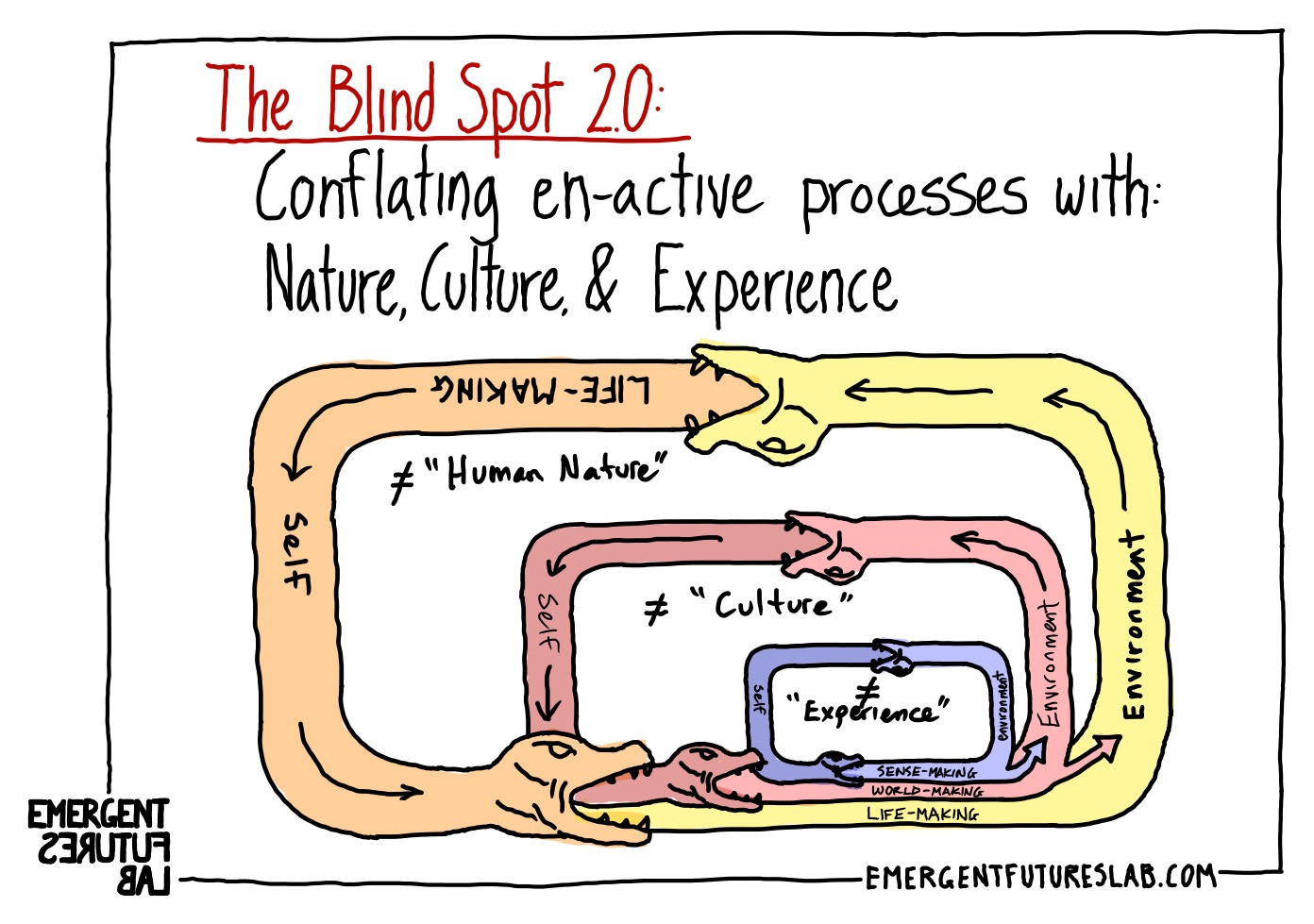

These ongoing creative loopings are not operating at one temporal scale: that of our individual experience. To paraphrase John Protevi: the individual embodied experience and the social are not distinct events happening on discreet levels but linked, looping and spiralling processes that are co-creatively intra-weaving across three temporal scales (we first introduced this in Volume 193).

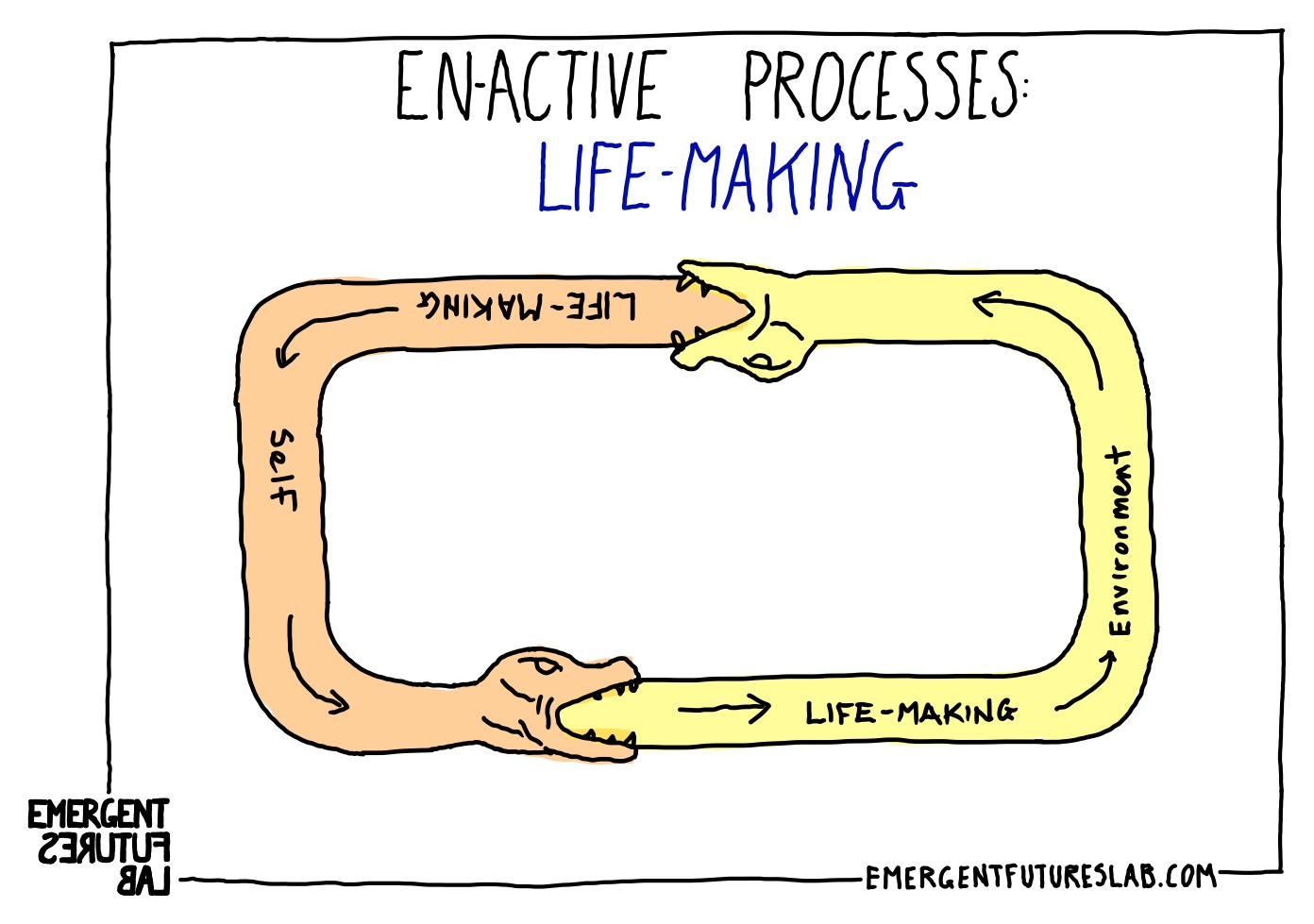

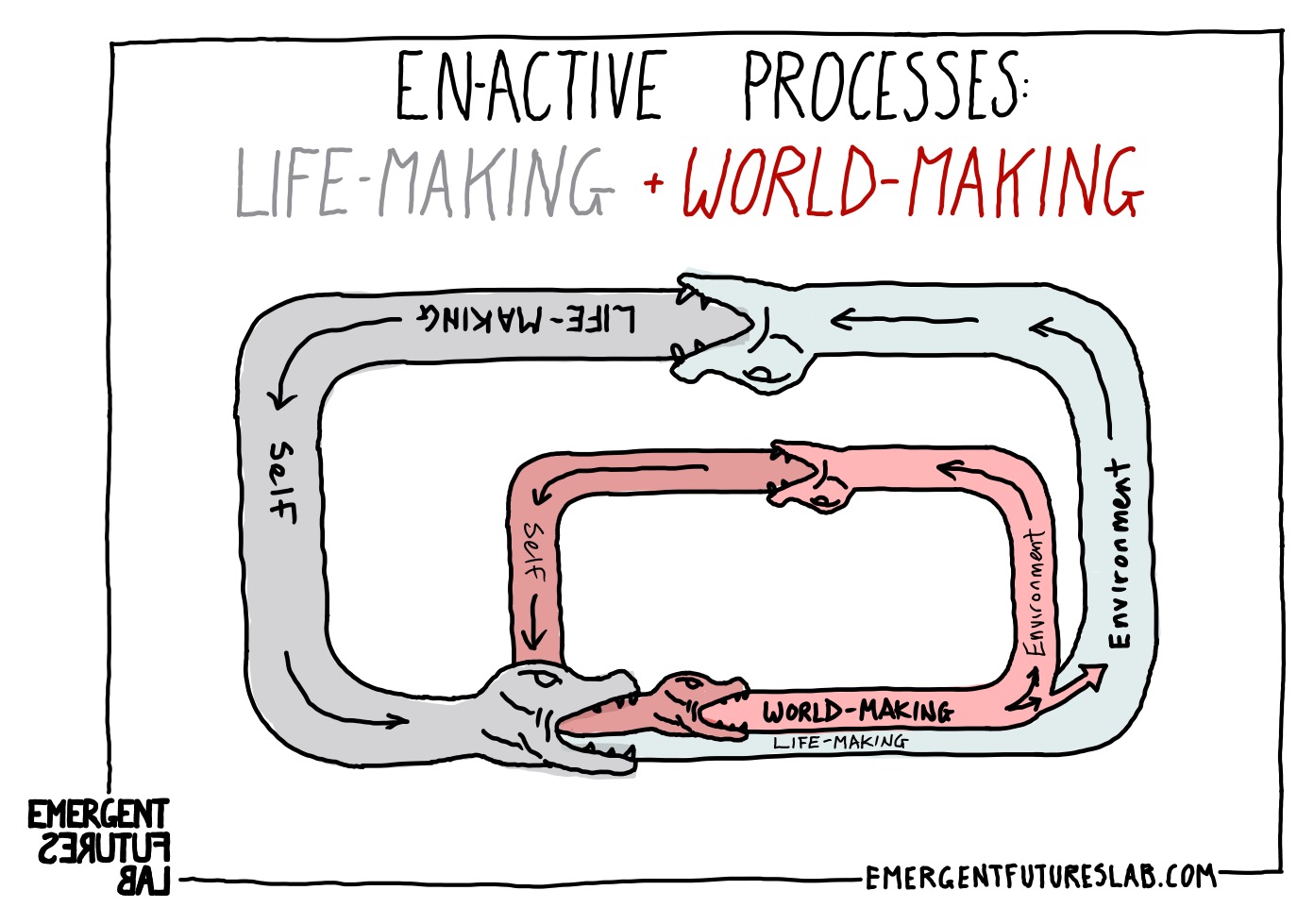

It is critical, before getting into the details, to clarify: This division into three loops is a useful abstraction. And while we, by necessity, present these loops one at a time, no temporal looping comes first, none takes precedent, and each transformatively affects all the others. Why three temporal loops and not ten or just one? It is because distinct kinds of qualitative change happen at these temporal scales, which we will detail below. All of these echo the basic logic of strange loops: we make our environment as it makes us: the dragon eats its tail, and as it does, it changes – sometimes qualitatively.

Life-making (0 - 10,000+ years):

There is the very long-term looping (thousands of years and more) of the forces shaping our species' inheritances of specific forms of plasticity co-created by the broad pattern of niche engagements and their agency. Examples: the emergence of tool making, semiosis, etc.

1. World-Making (0 - 100+ years):

At a shorter but historically long time scale (hundreds of years), we develop our culturally specific but general embodied capacities as we are embedded in the looping of specific historical ways/practices of being alive. These, in looping (action), fuse and transform irreversibly the loops of life making, for us: we become bio-socio-enculturated. Examples: the emergence of Naturalism, Animism, Totemism, Disciplinary Subjectivities, Individualism, and other Apperatuses/Dispositifs.

2. Sense-Making (0 - Weeks):

And at the temporal scale of everyday activity (days, weeks, and years) and a life lived as historically specifically bio-enculturated beings, we act/react to encounters in our already specifically meaningful environment/habits. Examples: the emergence of specific habits, practices, and tools, etc.

We are certainly aware of these three temporalities, but we sense them from within our blind-spot as: Human Nature, Culture, and Experience:

What does it mean to sense them from within our blind spot? It means that we are totally and utterly blind to the transformative co-shaping power of these as events in their strange looping. This is most visible in how we conflate world-making with “culture,” “world-view,” and “mindset”.

What does this mean in practical terms? We take our average everyday experience of reality to be a universal experience – and in doing so, we are surreptitiously confusing our mode of being alive (a world-in-the-making) with the way of being alive.

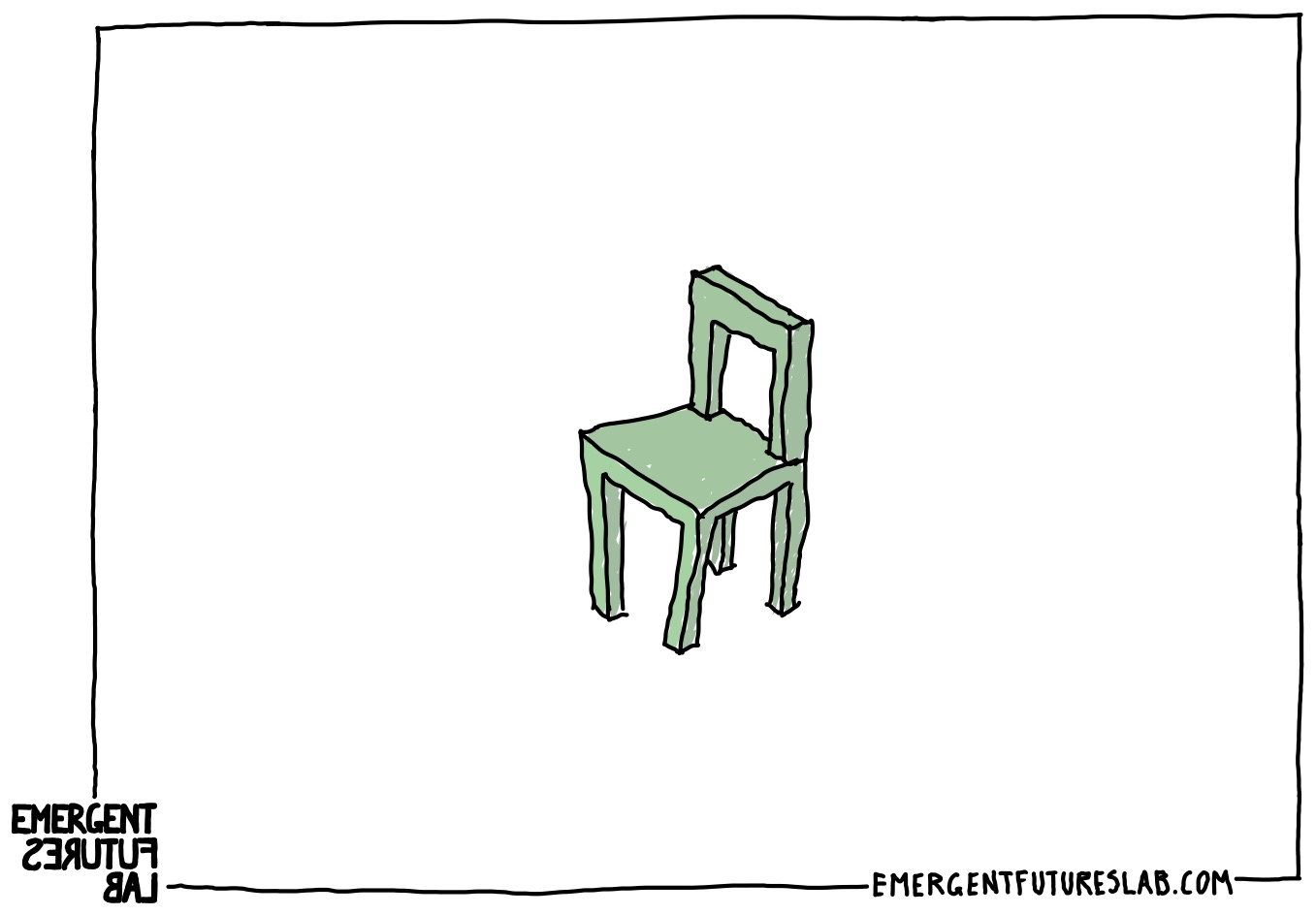

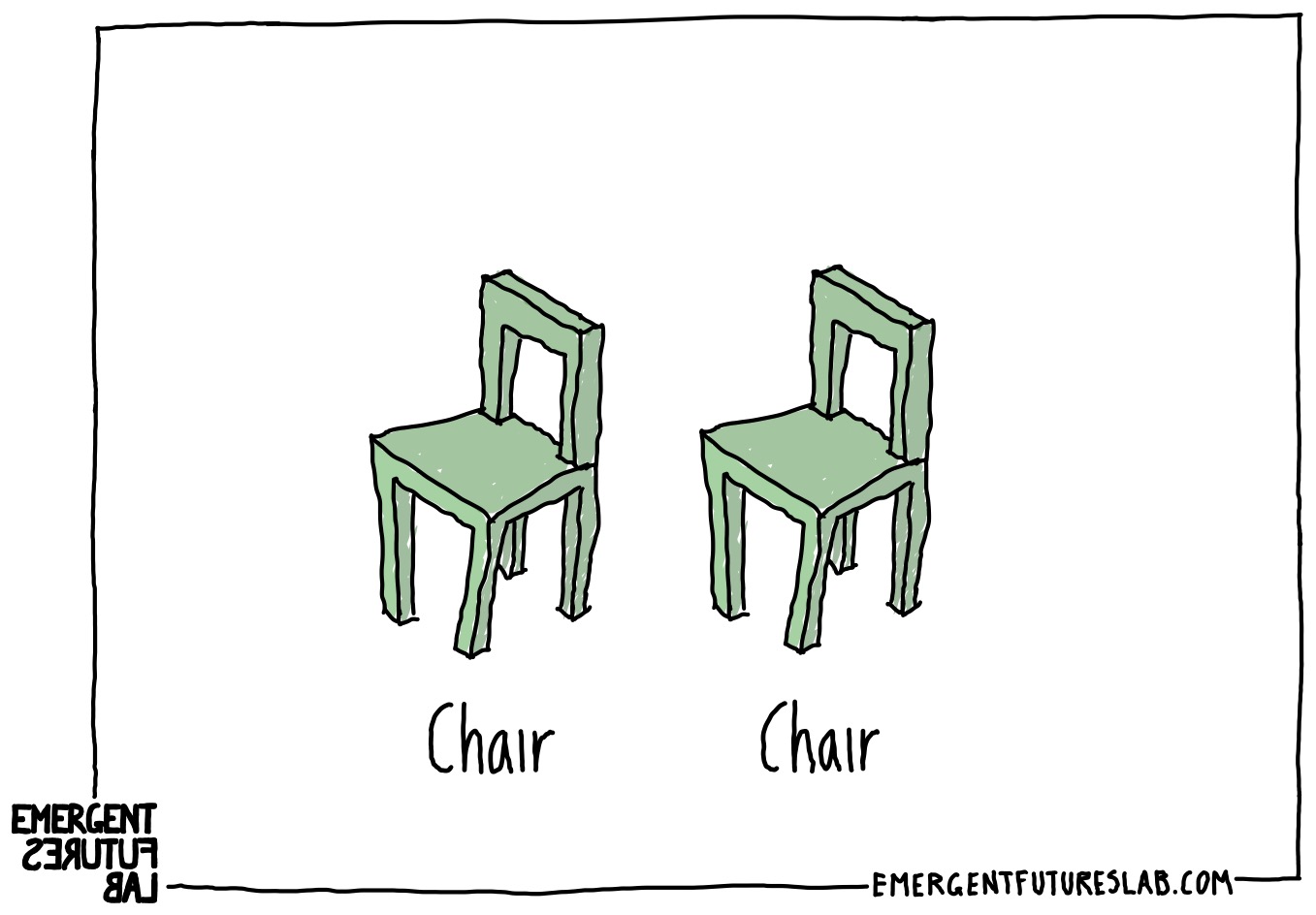

Here is a simple example: you see a chair in front of you, do you think “that is a chair – and while other people might have different feelings about chairs, or even not know about chairs – but basically if they were standing beside me and looking at this same chair – we would be seeing pretty much the same thing.” That's world blindness – and ultimately, en-action blindness.

How so? Let’s return to the newsletter from two weeks ago. In that newsletter, we offered two books that quite deliberately engaged with Japanese activities so that we could explore this topic. One book was on Origami, and the other on how to approach organizing your house from a Japanese minimalist perspective. Now you could just enjoy one book for your own pleasure of folding paper, and the other might help with the pleasures of the activity of reducing your household items. That is all perfectly fine (and certainly part of why we suggested them). But if we were to stop at this – seeing these as neutral activities, we would remain blind to what is different from minimalism or paper folding from within this historical Japanese mode of being alive (aka a unique historical and geographical mode of enactive “World-making”).

Let’s now dig into this example a bit deeper. A while back, I (Iain) had this text chat with a Japanese artist friend, Ayumi, who teaches “English for artists” as a part-time job. She had posted:

“I’m not a big fan of drawing human faces. It’s just not for me.”

And so I replied:

“...I am also not that interested in drawing humans or human faces. But I would be far more interested in drawing humans if we understood that socks and chairs are also humans.”

And from this, a very interesting and brief exchange ensued:

Ayumi: I got you. I might be off the track, but what you are saying sounds like 擬人化/擬人法 (gijin-ka/gijin-hou) in Japanese, which translates into “personification” in English.

Here in Japan, we use this gijin-ka more in our daily life compared to English-speaking cultures. For instance, we even call a sweater “her(or him?)” instead of “it,” especially when the person likes the sweater and/or has some kind of great emotion to it. The funny thing is that it's not even grammatically correct.

Iain: Yes -- I like that very much, especially if taken literally: the sweater, socks, and myself are all equally “persons” – we just show up differently -- e.g. socks = a person-that-socks, while Iain = a person-that-humans, etc.

Ayumi: I have a feeling that our (yours and mine) literal sense is different because of our cultural differences, and I’m not a master of my culture, but I think our religious beliefs, based on Shintoism, creates this gijin-ka integration in our daily lives. Traditionally, Japanese people believe there are hundreds and thousands of gods out there, and every object has its own god. Our gods are more like spirits. That makes us appreciate and handle objects more carefully, like caring for (human) others. We even hold memorial services for some objects, such as needles, dolls, and chopsticks.

Iain: Yes -- this is one thing I so appreciated when we were in Japan. I am trying to develop my own new ways of sensing the things that in my history were treated as inanimate as animate and human -- chairs, socks, pens, needles, etc. It shifts in a very radical sense what it means to make or transform something (a tree to a chair, for example). I am curious how you think of this transformation?

Ayumi: Thank you for your question. I’ve tried to articulate my thoughts on your question, and here is my take on it. It may be a bit confusing, so let me know if you need more explanation.

First of all, Japanese people do not articulate as much as Westerners do in our conversation. As I mentioned in prior comments, our literal sense is different from yours. When we speak, everything is more vague and ambiguous compared to Western literal communication.

For instance, when we say the word “tree” in our conversation in Japanese, it could be a single tree or multiple trees. There is the word “trees” in Japanese, and we use it, but we don’t have to. We understand the number of trees by the conversation we have. Japanese people tend to “read between the lines” constantly whenever we communicate with each other.

Another example of vagueness in Japanese conversation is that we don’t mention the subject every single time. We start conversations without a subject, and that happens all the time. Also, we don’t use pronouns that much. We don't articulate “who” in our conversation as much as you guys do in English.

Going back to your question, “what it means to make or transform something (a tree to a chair for example)”

Traditionally, “who” is making or transforming is not that big a deal. We appreciate the fact that we get the opportunity to make/transform something. (That is why craftsmen don’t get enough credit for whatever they do in Japan. and we need to change that).

Moreover, our spirits are flexible and transformative. One specific spirit represents one subject(object?) and also multiple subjects. A spirit of a tree can transform into a spirit of the chair. We don’t really think there is one spirit which represents one subject or a matter. It’s more like, there is a spirit and the spirit follows wherever and whatever the subject(object) becomes…

I know Japanese people are living in a vague and flexible, strange world!

I need to study more, but this is how I think so far.

There is so much of interest to explore in this short discussion. Let's start with a seemingly simple question: So what then of our chair?

Would you want to say that Ayumi enacts the same chair as I do? And that it is just her culturally subjective take on it that gives it a slightly different “flavor”? Which is to say we all share the same basic reality, but some of us are wearing different cultural glasses that cloud (or simply “shade”) what we see (really enact)? Ayumi is wearing glasses that add a bit more metaphoric “spirit” to the chair, and I am wearing glasses that make it seem more like “stuff” – while if we both took off our glasses, then what? Would we both see that we are just looking at atoms floating in space? Notice two things about how we are now speaking:

But, in one enactive world, this chair is an animate being, and in the other, it is an inanimate object. Ayumi and I, as enactive situated beings, are not encountering the same thing.

Ayumi articulates this beautifully: “I have a feeling that our (yours and mine) literal sense is different because of our cultural differences…”

I am the enactive outcome of a world enacting an inanimate object composed of wood fibers that was once a living tree and a subject (me) that enacts this form of sense-making as lived experience. Such that while I might deeply love and care for this chair – and even consider it metaphorically alive or still in possession of something of the tree’s “life” in it – it is still very much an inanimate object – I will not be giving it a funeral.

While Ayumi, as the enactive outcome of a very different world-in-the-making is enacting a qualitatively distinct chair, one that is an enspirited being that is similar in status to herself. A living being worthy of certain forms of care and protection that are categorically similar, as she says, to “caring for (human) others” – where such care would extend to a funeral and prayers.

While it might occupy the same physical location, It is not the same chair.

Can we sense this?

And can we sense that we most often don’t see this – and don’t see that we don’t see this?

Often, we will hear people say, “Isn’t it interesting how we all see things differently?...”

And it is correct that there is variation in all of the ways we make sense of things. But there are also clear general regularities in how we sense things. These regularities do not exist only at one scale: that of personal experience (sense-making). Hopefully, what has become visible in this brief dialogue between Ayumi and Iain is that there are regular differences that have emerged at the scale of world-making (specific historic regional modes of being alive).

These differences in sensing the chair as a “being” or a “thing” are not primarily personal differences in how Ayumi and Iain experience chairs – they are worldly differences. And as worldly differences, they are shared generally speaking by all who participate in these two distinct modes of world-making.

Our personal ways of making sense of things are in and of a collective historical and most often regional configuration of world-making practices. But since this is all experienced as “experience” – as just how “I see reality…” we are blind to this regular and regulating creative scale of the activity of world-making.

What we are blind to is activity – and how we are of activity – that the activities we are engaged in are irreversibly transformatively shaping us: En-action. Our historical Western enactive practices have made us sense ourselves as a type of universal ahistorical subject shorn of a material body, context, and given the unique power to see things as they are, act rationally with free will, standing just outside of the complex mess of ongoing reality. In this, we are ultimately blind to creativity. We are convinced that it is something we possess. But creativity – the process by which the new comes about – adheres to and emerges from activity. Our activities do not begin with ourselves, nor do they begin from a clean slate. No – they emerge from and are conditioned by ongoing activity – activity that is happening across multiple temporalities: Life-making + World-making + Sense-making.

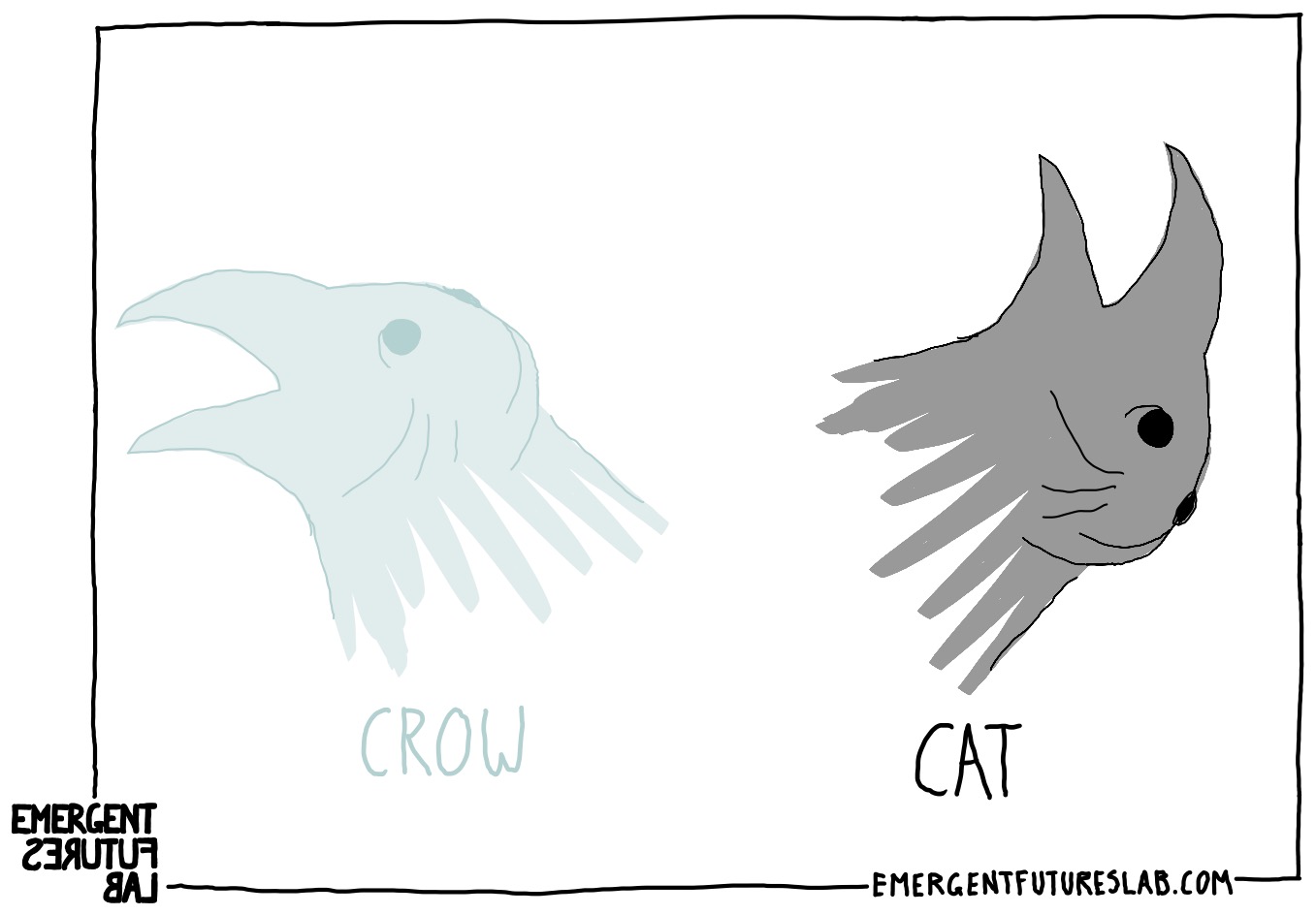

There is no getting out of these temporal loopings of ongoing en-active becoming. But, we can step out of our creativity blind spot and enter the enactive stream as an enactive co-creative stream. We can sense that what we “see” is what “we” (never alone) enact. And that when we see (enact), say this beautiful crow:

It is not the only way it might be enacted and sensed/seen:

And that this will be equally true of the enacted chairing:

The chair does not exist outside of an ongoing activity of a world-in-the-making.

In and of one world-in-the-making with subjects who are also in and of this world-in-the-making the chair is a person, and equally, at the very same moment in and of another world-in-the-making with subjects who are in and of this world-in-the-making, it is an object.

Crow - Cat. Chair – Chair.

And while we cannot just will ourselves to see and be different (that is the illusion). I, for example, cannot simply will myself to be “Japanese” and magically see chairs that are persons, or “personified”. I can, with skill, care, and humility, experimentally engage in enacting collaboratively a configurational shift that might lead towards differences that make a difference across the temporal scales of Life-making, World-making, and Sense-making.

Take a moment this week – is there a way to return to these activities we suggested in newsletter 197 now, differently? Can we work with an enactive creativity at multiple temporal scales? Can we enter and join the (enactive) stream fully? Try it and let us know how it goes…

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.