WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 206! Reading Within Creativity...

Good Morning non-legible becomings in the shock of words and readings,

After Andrea, Barry, Chantal, and Dexter tried with great creative ingenuity, but could never quite make it, finally, over the last few days, we felt the effects of Erin, the first named storm of 2025 to become a hurricane. Beautiful rains, big surf, and cool winds – what a welcome surprise in August in New Jersey. This morning, before dawn, the sky is clear, the moon is the smallest of slivers rising just before we rise and welcoming us into the light of the day just as it goes dark. Sometimes the smallest of slivers is more than we need.

Over the decades of working in, around, and with others engaged in creative processes, we have often been asked who most inspires our unique approach to creative practice. And while there is no real way to answer that question, somewhere in the interesting discussion that follows, books come up, and the question inevitably shifts to “what books might we recommend?”. Again, a challenging question to answer – as if there was one magic book, person, insight, or practice that would have all the answers… But, we do get the sensibility of the question: “where else can we go for more that also inspired you?”

Putting aside the desire for that one book or person that has all the answers, there is a book that has been very catalytic for us, and that most of our practices have evolved in an experimental dialog with. One reason for this is simply that it is a book we have been reading for a very long time – it is a book that we began reading in the late 1980’s. And this is A Thousand Plateaus by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari – first published in French in 1980.

Before jumping into experimenting with A Thousand Plateaus’ let's just say a few words by way of introduction to this newsletter series. It has become something of a tradition to begin the summer with a fun summer reading list – light experimental books engaging in a broad way with key questions in regards to creative practices. And then to end the summer with a different reading list of more dense and theoretical books on key areas of interest to those engaged with emergent creative processes. This year, to mix things up, we have shifted this logic. The summer reading changed into summer practices (Volume 203), and the fall’s bibliography of key resources has become a more focused look at one book (the next two newsletters, where we will focus on A Thousand Plateaus).

We hope to continue to do this deeper focus on single books as an intermittent series in the newsletter, perhaps once or twice a year.

How we are approaching this series: These wider and more engaged dives into single books are neither reviews nor guides. They are not reviews in the sense that we will not be assessing books. Good, Bad. Best, Worst. These assessments have their place – but when it comes to questions of creative engagement, they have little value – for what one manages to do with a book is an ever-open question. Too many books of future Nobel Prize winners have been rejected dozens of times by an editor who lives in the narrowness of the knowing and knowable present and deemed Samuel Beckett, Gertrude Stein, or Amiri Baraka not worthy of publishing. But, as Deleuze argued, creative experiments are done for “a people yet to come.” We have to change ourselves to become worthy of great experiments.

In this series, our takes are also not guides; again, these can be of great value – but they can also be an avalanche that buries the book long before you can get to it and invent new ways to work with it.

We would rather be seen as charming dinner conversationalists recounting our often failed experiments in a way that might beguile you into finding your own way to dance with these rhythms and begin your own experimental apprenticeship with their relational and emergent signs.

And… let’s dwell on one more approach to so-called “important” and “big” books – you must have read them and must display them prominently. You must refer to the authors by abbreviated first names – Bill, Bob, Gilles, and Felix.

For us, there is nothing more tedious than this stance of the universally well-read who can parrot the perfect phrase on any author and topic, and render the seemingly perfect universal judgement. For us, we read books because we are pulled into them by a curiosity and concern that awakens experiments in us. Do these experiments align with the authors'? We are not that certain, and not fully concerned. And, if a year or two later you were to ask us about these authors who were so important to us at one point, we are not sure we would have anything useful to say – we would have to start again if you asked us about the authors.

Our personal experience (for what it is worth), some books take twenty years to get into, others take equally long to read, and yet others you might read a few times before you could say anything. See what happens, avoid the AI cliff notes and the polemics, and give yourself time to go where you go.

If you don’t have a copy of A Thousand Plateaus, we would suggest pausing to get a copy – ideal would be in French, but the translations are works of art and offer great insight in their own right – you can find it used in English – with the wonderful translation of Brian Massumi (who also wrote a wonderful book on it: A Users Guide to Capitalism and Schizophrenia) for a good price on Biblio – or just call up your favorite book store to help you source a copy (what ever you do we suggest avoiding further enriching Bezos).

We plan to dig into A Thousand Plateaus next week, and this week to provide some context – so if you can crack open the book before next week, that would be great.

This week, we begin our circuitous approach with a detour into the two authors, Gilles Deleuze (Died 1995), and Felix Guattari (Died 1992).

That there are two authors is already something quite novel and unique, and is very consequential to the logic and success of their shared project.

Gilles Deleuze, a French philosopher, who was born in 1925, described his interests as primarily involving the what and how of processes of creation and creativity – the event of the new. This focus on the conditions by which everything comes into being, which he had for his whole career, makes him quite unique in the history of contemporary Western philosophy.

His self-described naivety and profound logic affirmation around issues of creativity allowed him to continuously ask genetic questions – questions about the genesis of anything and everything: How did this thinking come into being? How did this subjectivity emerge? How did we come to have the categories of subjects and objects? And what else is possible? And it is this insistence on the processes of creation and the processes of creativity that necessarily exceed identity that make him an essential touch point for our own experimental practice and its focus on the what and how of creativity: “Yes – and, what else can it do?”

Felix Guattari, born in 1930 in the outskirts of Paris, was far less of a traditional academic – he was a dropout from both college and a pharmacy program who became an important thinker and activist. He was deeply involved in political struggles both in France and globally, and collaboratively directed an alternative psychiatric institute that focused on group creativity rather than individual psychosis. He ran for political office, helped run an alternative radio station, started magazines, and set up organizations to foster new spaces of liberty.

He was and is an important thinker in his own right who has, unfortunately, been in many ways overshadowed by Deleuze. He wrote a number of important books on creativity, ecology, and modern subjectivity. His final book (he died quite suddenly of a heart attack in his early sixties), “The Three Ecologies,” is another critical book for us. In it, he looks at how our mental, social, and environmental ecologies have been historically co-created by an ecology of bad ideas, practices, and environments and proposes new creative approaches to developing alternative ecologies. Here, the concept of ecology is not meant in the purely environmental sense of, for example, a rainforest ecosystem – rather, the processes that lead to the emergence of everything require a dynamic ecology for it to emerge and function.

The Three Ecologies, while written in 1989, over thirty-five years ago, is ever more relevant in this age of “mindset” focused ideas of subject-driven individualized change. It offers a far richer alternative approach to creatively inventing novel mental ecologies in an intraconnected manner with social and environmental transformation.

A Final Concept: Guattari was a great inventor of concepts (they define philosophy in their last work together, What is Philosophy? as “the practice for invention of novel concepts”), and one that plays a significant role in our practice is Transversality (See Transversal, and Thicket in our Glossary). And, as we will see when we move to engaging experimentally with A Thousand Plateaus – transversality, the unpredictable, surprising sideways movements of all things – give this work its unique consistency and highly innovative style.

Finally, the concept aptly articulates Guattari’s own ethos and energy: moving across fields and experiments with little regard for traditional boundaries and divisions.

If judged by overt and superficial signs – upbringing, temperament, formal identity, and so-called personality – it would appear that they were a more than highly unlikely collaborative team. The “quiet” and withdrawn philosophy professor and the peripatetic “activist”. That they met and began working together – and worked together so powerfully – is not something anyone could have predicted.

They both spoke very insightfully about their collaboration, and much of this is detailed in the joint biography Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari: Intersecting Lives. Together, they had this to say about their first collaborative book:

“The two of us wrote Anti-Oedipus together. Since each of us was several, there was already quite a crowd. Here we have made use of everything that came within range, what was closest as well as farthest away. We have assigned clever pseudonyms to prevent recognition. Why have we kept our own names? Out of habit, purely out of habit. To make ourselves unrecognizable in turn. To render imperceptible, not ourselves, but what makes us act, feel, and think. Also, because it’s nice to talk like everybody else, to say the sun rises, when everybody knows it’s only a manner of speaking. To reach, not the point where one no longer says I, but the point where it is no longer of any importance whether one says I. We are no longer ourselves. Each will know his own. We have been aided, inspired, multiplied” Deleuze and Guattari

Coming back to the story of how they met: Guattari, had read Delueze’s work – who by this point in the late 1960’s had written nine books, all highly original while being mainly in the guise of monographs on other philosophers: Hume, Nietzsche, Kant, Proust, Bergson, Sacher-Masoch, and Spinoza – as well as two works on creativity – one a metaphysics on how anything comes into being and the other psychoanalytical novel about events: Difference and Repetition (a book that we often imagine in a parallel universe replaced Heidegger’s Being and Time in terms of impact) and The Logic of Sense.

Guattari had written to Deleuze and shared with him his own emerging concepts. Deleuze responded – and this began their primary mode of collaboration – a lifelong written correspondence for the co-creation of concepts: Guattari writing down not fully worked out conceptual trajectories and Deleuze responding to them.

But back in their early days, it was only after a brief correspondence that Guattari, with the aid of a mutual friend, travelled to the village where Deleuze was staying for the summer, bedridden, recovering from the removal of one of his lungs due to tuberculosis. From this something special emerged – here is what the French artist and poet Jean-Jacques Lebel, who brought them on a tour of the US, said:

“We took what they call the "red-eye" flight. Félix and I sat together, and Gilles sat with Claire Parnet. Claire fell right asleep, and Gilles and Félix talked nonstop for seven or eight hours about their ideas in Anti-Oedipus and A Thousand Plateaus, which they were working on at the time. It was like an interminable living laboratory, which they left occasionally to live life, but to which they quickly returned. I was listening to what they were saying, like I might listen to Rimbaud or

Nietzsche”

Their lifelong abiding, shared, and mutually transforming concerns revolved around a collaboratively emerging radical approach to creativity. Perhaps this sounds strange, but it is, after all, not often that we find philosophers in the West Asian tradition interested in creativity per se. Most philosophers are interested in Being – what exists and how can we know it – Ontology and Epistemology. Both Deleuze and Guattari are interested in becoming ontogenesis. And what is becoming but another word for ongoing creation – creativity? Deleuze and Guattari – from their very different starting points – the philosopher and the activist – are both interested in change and how change can happen. This requires both a critical analysis of historical creative practices: how things came into being and persist, as well as an understanding of how change is possible and how we can participate in it.

Not the classical Greek question of: what is it? But always – what else is possible?

For the sake of this brief introduction, we can understand that these two questions are underpinned broadly speaking by four concerns (that are the concerns of creativity itself): time, immanence, multiplicity, and difference.

The two of them came together in the aftermath of the widespread student protests in 1968 to work on a project to rethink identity, subjectivity, and desire from the perspective of radical creativity, where identities, or universals, would not be assumed to be a priori givens. The book that emerged from this astonishing collaboration, Anti-Oedipus, was one that Michel Foucault would go on to call “a primer in anti-Fascist life” – something that is still in much need today.

From this they would go on to write three more books over the next two decades: A Thousand Plateaus, Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature, and What is Philosophy.

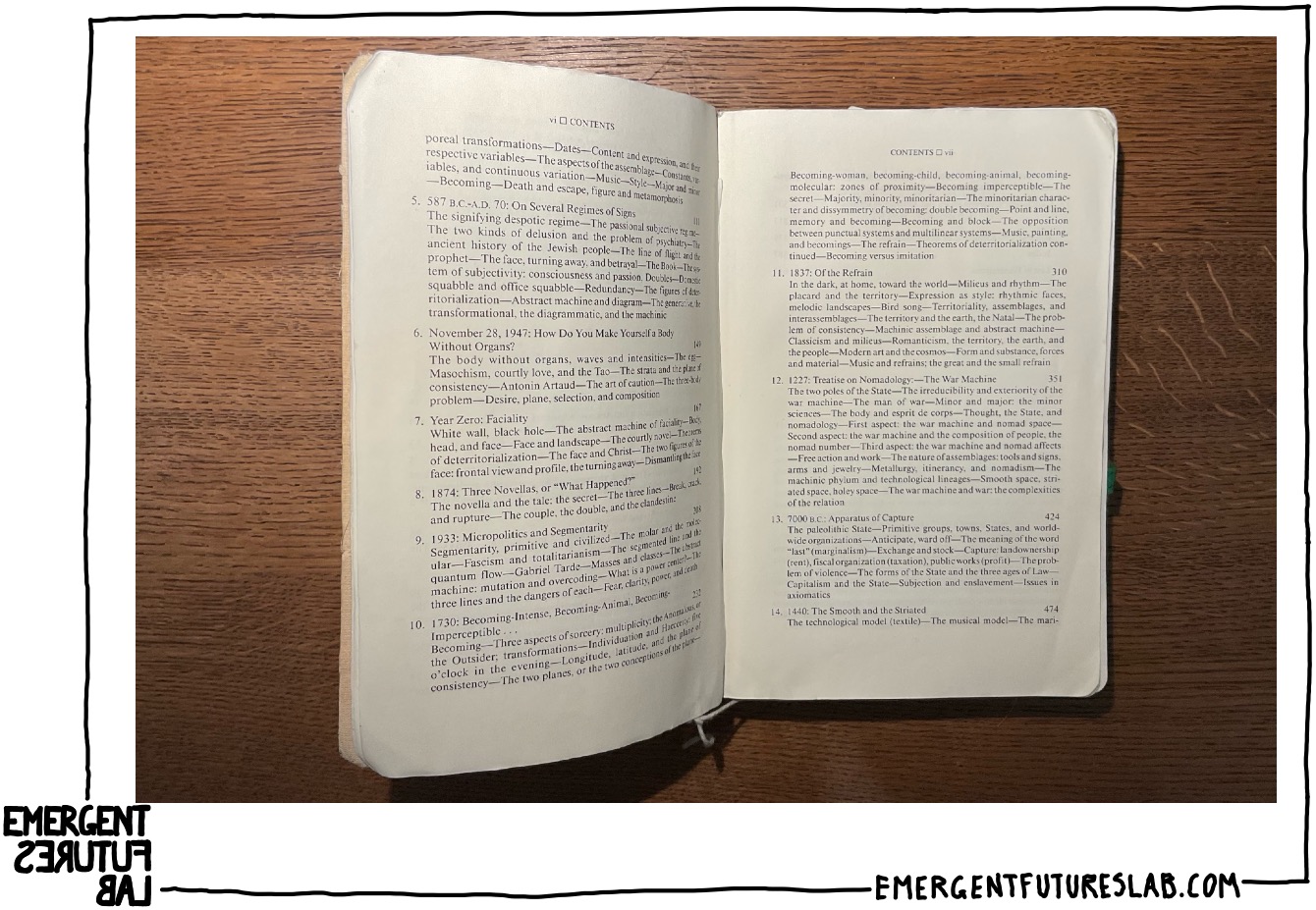

When you crack open A Thousand Plateaus – just looking at the table of contents or flipping through the pages – you are met by many odd terms – rhizomes, bodies without organs, war machines, smooth and striated spaces, becoming-animal, abstract machines. Then, for a book of philosophy or creativity, it seems all over the place: it begins by focusing on trees, roots, and rhizomes – then wolves and wolf packs – next deep time and geology…

What is the common thread here? What should we do with all of this?

It is helpful to pivot away from the book and consider the bigger critical task for Deleuze (and us): how do we change how we think?

But before getting to the question of how we might change our thinking, we have to have some sense of what is “thinking”?.

For Deleuz, this is a critical question – and one that he argues in a book he wrote in the late 1960s, Difference and Repetition – far too little thought is given to it in the Western traditions. Here, the assumption is that we are almost always thinking – we are a naturally thinking species. And that is when we think our natural inclination is towards getting to the truth – the correct answer. Thinking is both natural and naturally inclined towards the truth. Thus, we name ourselves the wise humans – homo-sapiens.

But what we are doing most of the time is far more rote and automatic than thinking. We are in our routines and habits. We are in cultural habits and practices. This is one reason that AI – a token-based statistical pattern recognition system, is so good at mindlessly parroting generic letters, overviews, poems, and conversations. The truth is that most of the time when we do these types of things, from idle conversations to writing emails, we are also accessing and mimicking deeply entrenched statistical patterns. Is this really “thinking”? This is best understood as something else, and thinking is best understood as the activity of being able to develop novel propositions, concepts, and conceptual trajectories.

This is the world of received opinion – “what everybody knows” – the world of well-established identities, patterns, perceived resemblances, and fixed representations. Deleuze terms all of this representational thought, and that non-creative thinking is re-presentational, is critical to his approach to creativity. And this – re-presentational thought, is for Deleuze, the enemy of thought.

If thinking is something other than this highly habitual, nearly mindless activity of generating acceptable standard responses, it must, for Deleuze, involve the thinking of the new. Thinking and creativity involve going beyond the given. But this is where re-presentational thought reaches its limit – confronted and shocked by the radically new, this form of thought is forced to acknowledge:

“I don’t know!”

Because our everyday thinking is re-presentational, thinking the new does not – and cannot come naturally to us. When we think, and when we imagine, we are necessarily working with the known and the given (re-presentations). In a very real sense, we cannot logically simply think the new.

Representational thinking is a thinking that, by definition, turns the new into the given. We see, recognize, and know in one act: I see the table I am working on, my tablet, my glasses, some books, cables, notes, bills… And if there was something totally new in the midst of all of this – how would I even begin to recognize it?

“Something in the world forces us to think. This something is an object not of recognition but of a fundamental encounter” (Deleuze in Difference and Repetition).

We are forced to think by the shock of an encounter. Here, there is no correct answer, no understanding, no words, no concepts – nothing we can imagine – unless we turn the new back into the known.

Thinking – creative thinking is an involuntary adventure that begins at the limits of your re-presentational ideational thinking. In the shock of an encounter, beyond your knowing, your ways of sensing are pushed in new directions:

The new is first encountered in sensation – it is felt without being understood. And fundamental to thinking the new is to keep this event of feeling without knowing alive long enough that it can lead our sensibilities into new practices, assemblages, and active embodied states – from which new propositions and concepts might in time arise.

Now, back to the question, “Why is this so difficult?” From Deleuze’s perspective, the assumption that good writing, like good thinking, is singular, clear, simple, and accurate, is to miss the reality that this is not thinking at all. Thinking the new involves the shock of an encounter with a novel difference. It will exist and develop in a space of the vague, imprecise, and experimental. The style of A Thousand Plateaus is not wilfully obscure – rather, it is deliberately and carefully experimental in ways that will produce the shock of a genuine encounter. And here creativity asks of us to be ready to change to actually openly meet such an involuntary adventure.

So how does the book begin?

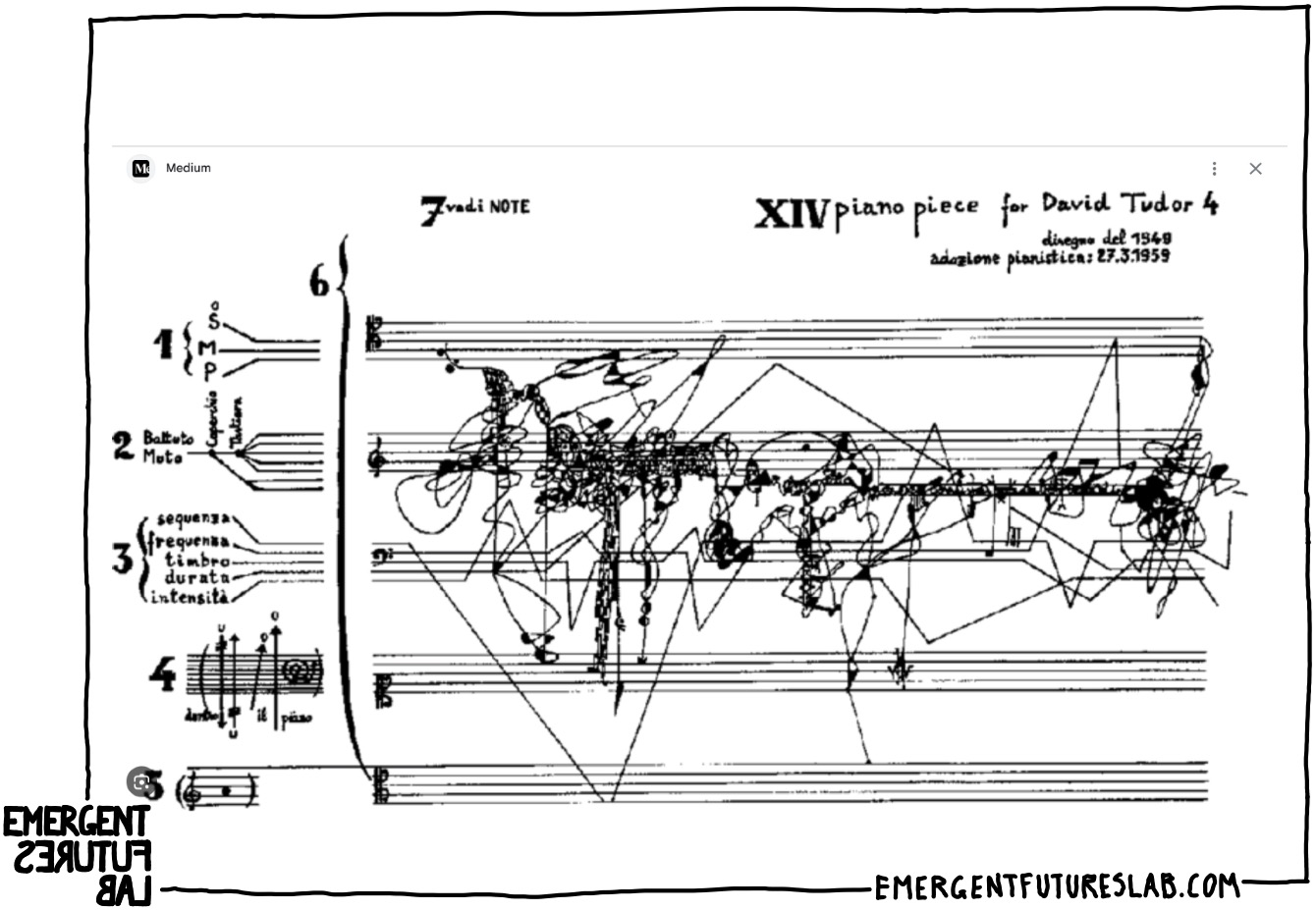

It does not begin with words – in fac, the book begins with an image from the fourth of five musical scores: “Five Piano Pieces for David Tudor” by Sylvano Bussotti – a contemporary of Deleuze and Guattari. Here is the image:

What are we to make of this?

For next week, we encourage you to find your way into an experiment with this score. It is playable. And it is important to the project of engaging experimentally with this book. Could you sing it? Do you have a piano or keyboard? Is there an app on your phone that can act as a keyboard? Could you try it in other ways?

We would love to hear what you do with it.

That’s it for this week. We hope that you have a chance to dip into A Thousand Plateaus at some point this week – and that you can experiment with this score. And in this and other events, you are pulled into unexpected encounters and adventures with difference.

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.