WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 2081 Creativity Begins @ “N minus One”...

Good morning experimental readers of the exteriority of relations,

Here it is as hot as ever on the north-western edge of the Atlantic, and a minor tropical disturbance of disorganized showers and thunderstorms south-west of the Cape Verde Islands is creatively co-emerging and tending towards becoming a tropical storm and perhaps even a hurricane in the next couple of weeks.

This emergent event is a dynamic, creative becoming worthy of a close pragmatic reading. There is a lot that the creative genesis of a hurricane can teach us about creative processes of individuation in our lives.

Out in oceanic weathers, we are engaging, feeling, reading, probing, sensing, abstracting, connecting, experimenting, stabilizing in highly creative ways.

A question as we return this week to continue our reading of Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus: can we experimentally read books the way we actively read the weather as sailors?

A Practical Creativity

Perhaps a few of you might involuntarily spit out your morning coffee when you read this, but nonetheless, we strongly feel that one reason to read A Thousand Plateaus is because it offers on every page and at every moment a primer in a “practical creativity”.

Now obviously Deleuze and Guattari’s “practical” cannot mean that this book will tell us “what to do” – or offer us an easy, simple, and perhaps guaranteed course of action. One reads wind and waves not for rules or guarantees – but for signs of ways to connect and sustain an experiment (sailing). So too with this book – how do we sustain an experiment in creative becoming without succumbing to chaos (dissolution) or catatonic rigidity (fixed identities)?

This book is never going to give us the non-relevant comfort of:

“If you find yourself in a complicated situation versus an obvious or complex or chaotic one then this is what you should do: sense, then analyze and then respond with a “best practice””.

But, nonetheless, at every point, this book offers an experimental “pragmatics” – Deleuze and Guattari are endlessly putting forth alternative ways to act, visualize, and experiment from the perspective of a radical creativity.

They want to attune us – help us to experimentally read the ongoing creative dimensions of reality that never disappear from any and all events – no matter how fixed or stable they might seem. And they want us to experiment – to read, sense, and feel from within our own actions, our own projects, and question what the dynamic creative dimensions might be and become.

Referencing our emerging potentiality of an Atlantic storm, becoming we might say in Deleuzo-Guattarian fashion: Minor and disorganized disturbances are everywhere, and everywhere creatively active, and if we can attune ourselves towards their rhythms, tones, and movements – in short, learn to read for difference – perhaps we can actively follow them into radical new possibilities.

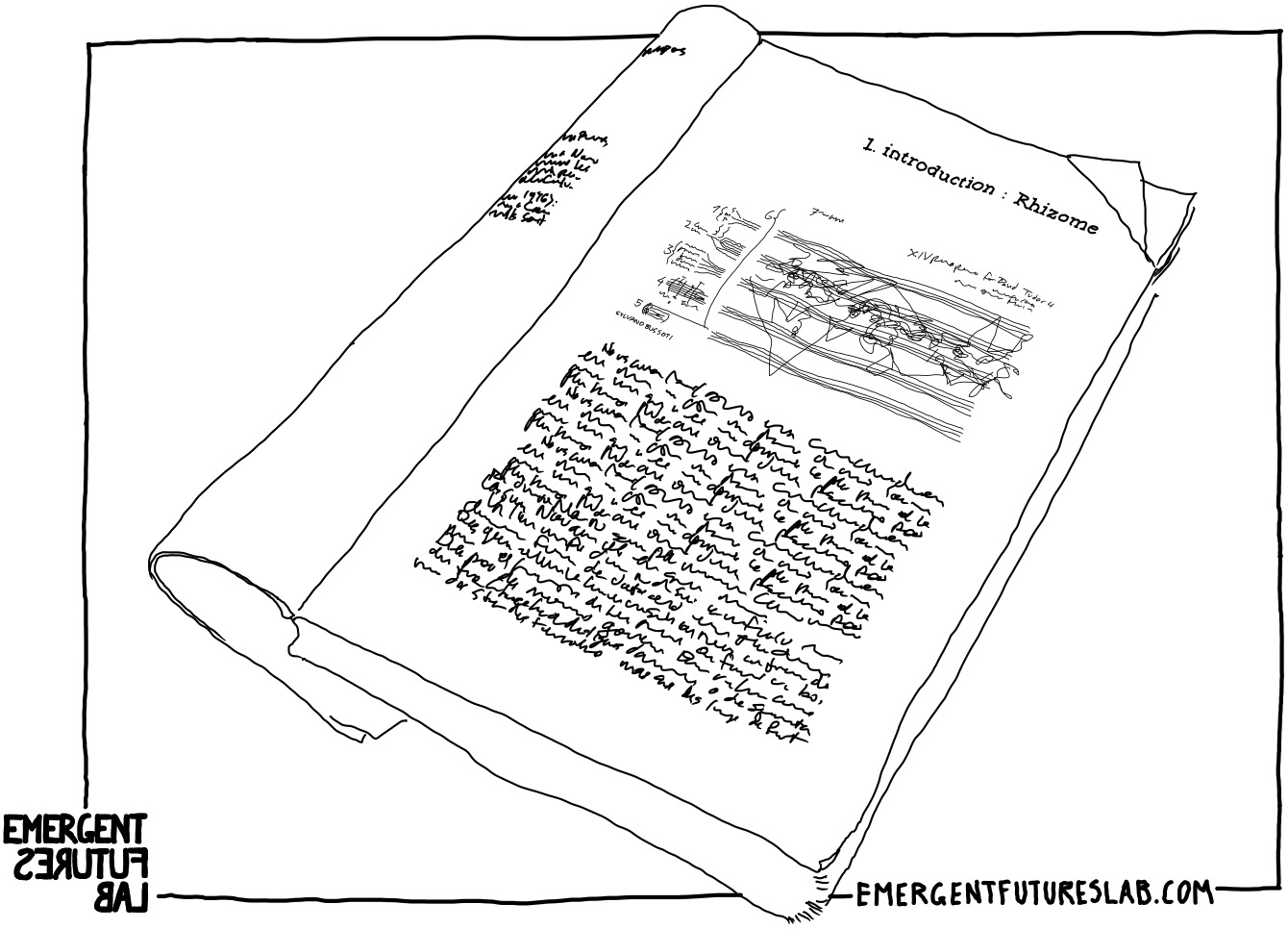

This desire of Deleuze and Guattari to bring us towards the practices of reading differently for the new (e.g., difference) begins immediately with the Bussoti score that is there at the top of the first page of A Thousand Plateaus (which we discussed and experimented with in last week's newsletter).

And then we immediately find this same sensibility with their very first sentences, which, while offering a description of how they worked, also offer ways into our own experimental practices. Let’s just jump into the book with the first four sentences to see this logic at work:

“The two of us wrote Anti-Oedipus together. Since each of us was several there was already a crowd. Here we have made use of everything that came within range, what was closest as well as farthest away. We have assigned pseudonyms to prevent recognition…”

And this is what we mean by their pragmatism: Already in these first four sentences, there is great pragmatic experimental creativity that we could tease out as heuristics to play with:

And that is just the first four sentences! From our perspective, the “problem” with A Thousand Plateaus is not that it is opaque and hard to grasp, but that it has far too much that is pragmatic to offer our creative practices. It is conceptually excessive. Already with these four sentences, we can radically challenge and change so much of what is taken as creativity. It is a density that forces us to put the book down constantly – to both try things out and to simply go for a walk!

This week, we are experimenting with three chapters or plateaus from A Thousand Plateaus:

1. Introduction: Rhizome

12. 1227: Treatise on Nomadology – The War Machine

14. 1440: The Smooth and the Striated

Now, while we hope that you have had a chance to read some or all of these plateaus, we understand if this has not been possible.

And we equally understand that on first reading, this book can be overwhelming – the references, tangents, and lists of all kinds can be dizzying and frankly exhausting – as we said, too many concepts!

This is a writing honking, buzzing, whizzing, and careening with life’s creative becomings – more Mexico City or Mumbai than the serene olive grove of Plato’s Academy or the quiet of a modern library study room.

As we stand in the busy traffic intersection of a megalopolis that is each of these plateaus, it is useful to recall the larger experiment that Deleuze and Guattari are engaging in: to bring creativity back into thinking – to force us to think.

And the creativity that they wish to bring to bear on our thinking is an all-encompassing creativity that requires approaching reality from a distinct and radically unique perspective: to believe in such a creativity is to see that everything comes into being, stays in being, and then changes out of being as and through processes that are themselves subject to dynamic change. Nothing escapes the relationally dynamic and open process of ongoing creation.

For Deleuze and Guattari, the processes of the new and the different are everywhere and active at all times, and because of this, they ultimately need no explanation. Rather, what needs to be explained is how things become stabilized, territorialized, and as they put it, “striated” – as well as how they are then also creatively kept the “same” in the dynamic “chaosmos” that is our reality (they love this portmanteau work of Joyce’s from Finnegans Wake that fuses chaos + cosmos).

Now, this perspective of the radically creative aspect of our cosmos is by no means the only valid perspective to engage with things. Other perspectives and problems exist, and other problems and perspectives can be invented. But sensing their perspectivalism is key to reading this work. One example of this is that everywhere they are making very strong claims, such as:

“Writing has nothing to do with …”

“The state is this…”

And this is where we need to add back into all their statements their perspective. What a statement like “writing has nothing to do with…” should say is:

“From the perspective of a radical creativity, let's experimentally posit that writing has nothing to do with _________ – and see where this could take us…”

This is a perspectival and experimental book through and through – a pragmatic book, a non-neutral book, an activist book – testing, probing, following, sensing, abstracting, connecting, experimenting, stabilizing, deterritorializing, and reterritorializing – and it needs to be approached in this spirit.

Where then to begin with such a seemingly massive task? For Deleuze and Guattari, from the perspective of creativity, we can only ever begin where we are – with this book in the midst of writing and reading. Thus, the introduction opens up with a long consideration of writing, reading, books, and language.

The passage near the beginning of the book that always strikes us with a force is:

“ Writing has nothing to do with signifying. It has everything to do with surveying, mapping, even realms yet to come… “

Let’s put aside for a moment the question of why writing has nothing to do with signification, and ask:

What do they mean by “mapping”?

They helpfully offer this:

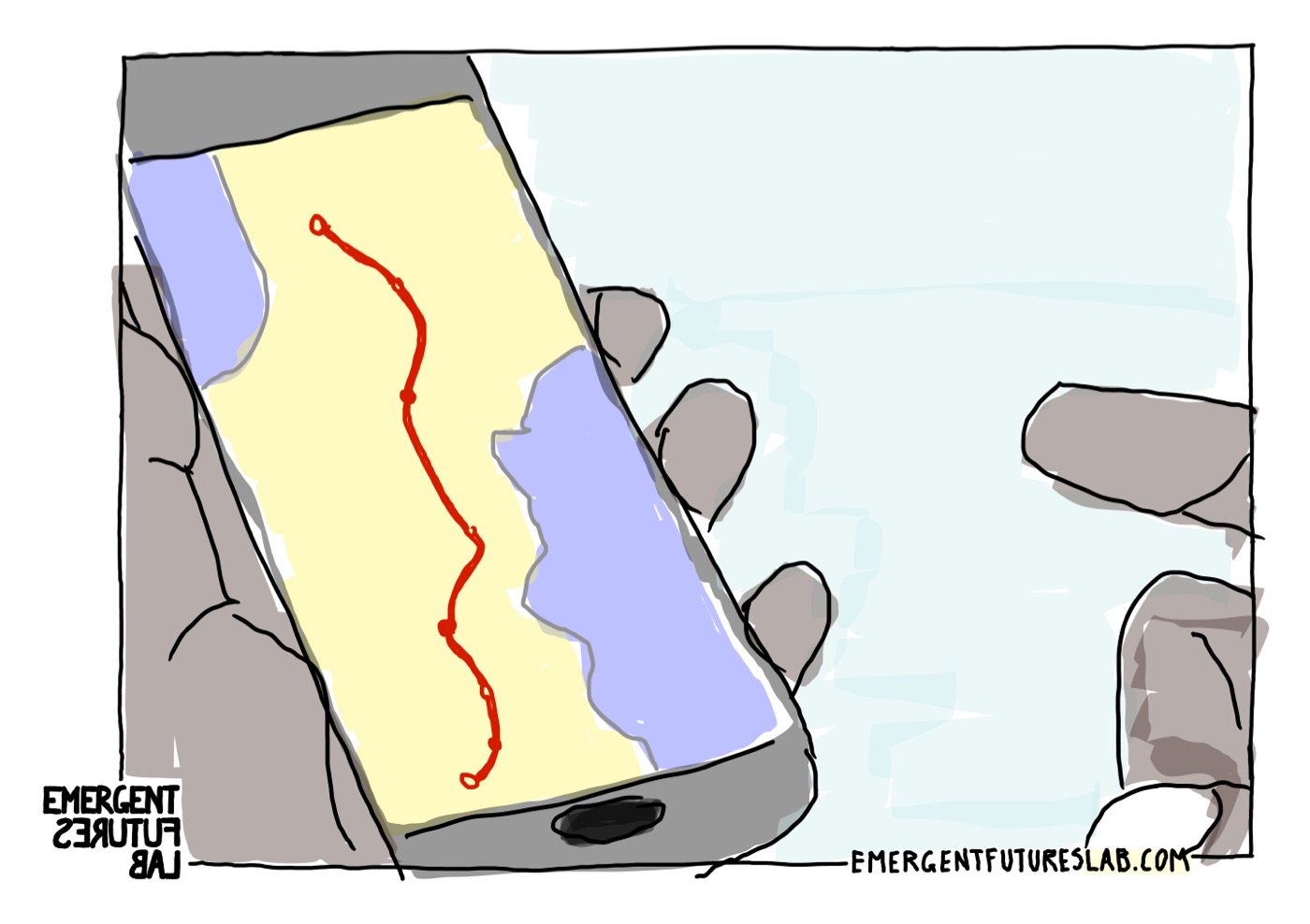

“What distinguishes a map is that it is entirely oriented toward an experimentation in contact with the real”

Maps – the big things that we used to unfurl in passenger seats of cars, coffee shops, on wind-blown mountain ridges, and unintentionally into the faces of fellow subway car riders – don’t simply allow you to find the Google directions from the Tarang Co-op Housing Society to the Raudat Tahera Shrine in Mumbai (for example):

Rather, they open you to everything else – What else is here? Where else could we go? This looks curious… What happens if we go this way? The map is not about itself, it is not about going from A to B – it is a tool for experimenting with the real and whose propensities are always to push those experiments towards deviations – towards the “where else?” and the “what else?” – away towards new connections, new encounters, new becomings:

“Look, there is a beach near where we are going – what if we go there?”

They critically contrast this form of writing-as-mapping with writing-as-signifying.

Why?

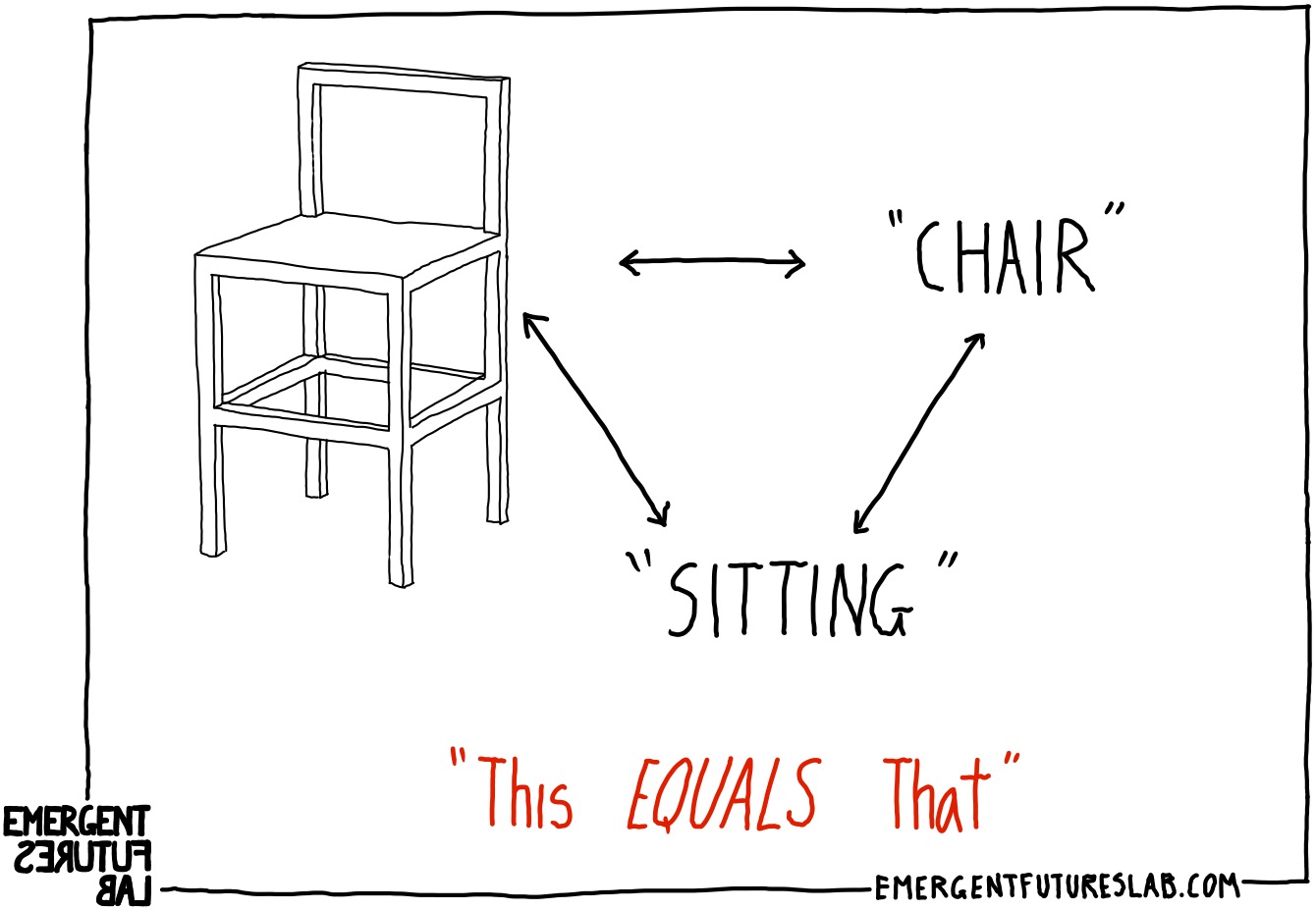

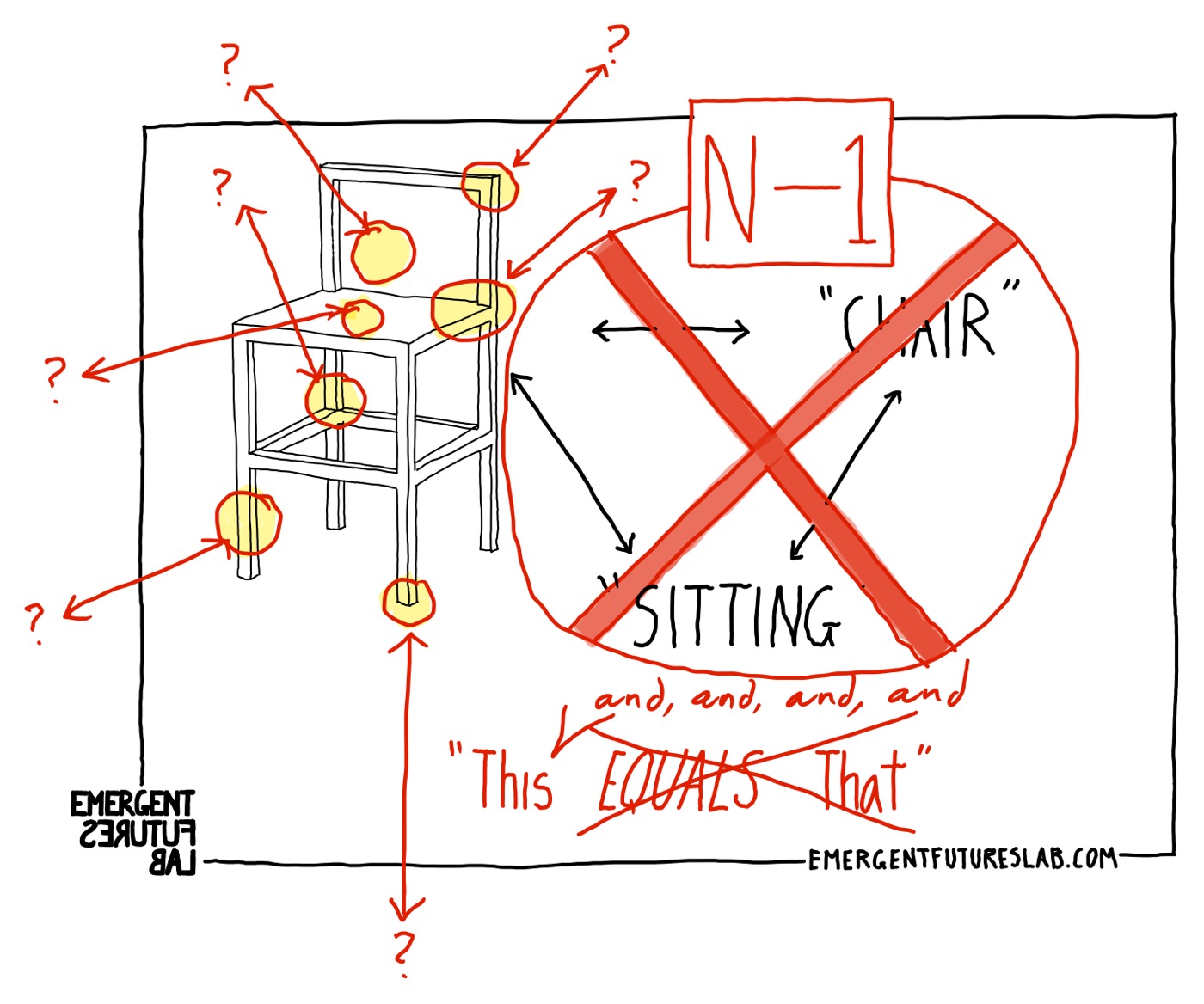

From an experimental and creative perspective, the process of signification is one of fixing, stabilizing, and ultimately stopping all of the processes of becoming and claiming that only one relation is the “correct” possibility (identity) of some thing. With signification, we make the claim “this is that”:

This is a chair.

And a chair can be defined as a specific type of tool for sitting, and sitting is its essential purpose. And that is what it is.

Signification is a practice that we all engage in – it is an anti-creative stabilizing habit that we have historically developed that chains things to identity and conflates them with identity and purpose.

So, yes, Deleuze and Guattari – they do ask us to begin wherever we are – in this case, literally with the reading of this book. But, as they make clear with this first contrast between ways of reading, this is not the only place we are beginning. We begin already shaped by a history of practices of thought and action – such as the practice of signification. And these practices have sedimented into tacit habits – that we take as how things are and how we do things “naturally”.

From the perspective of creativity, it will never be enough to offer an image of creative practices alone – we need to equally challenge our historical social practices of refusing, reifying, and stultifying these creative becomings.

To this end, Deleuze and Guattari are always asking in a very concrete manner: What are the habits that take us away from engaging with the ongoing processes of creation and creativity?

And very early on in this plateau, they make this very clear that three of the most common practices are:

Identity, Signification, and Attribution

Why?

All of these processes freeze the ever ongoing creative becomings with the imposition of a logic of “this equals that”. This is a chair (Identity) – and we can define a chair as having certain real attributes (Attribution) and then we can give it a fixed name (signification).

But… is this really all that a chair can connect with?

Everywhere in this book, we are confronted by pairings:

Signifying and Mapping

Smoothing and Striating

Rhizomes and Trees

The Nomad and The State

And it would be easy to fall into our historical habits of binary judgement: Rhizomes, Nomads and Smooth spaces are inherently good and States, Trees and the Striated are inherently bad.

But this is not what they are up to. It is always really important to remember what their bigger project is:

They are developing practices and tools to engage with an inherently creative universe as a creative universe. And to do this, they need to explain two things: (1) how, if everything is so dynamic, do things stabilize and stay the same? and (2) Why do we have such a hard time sensing, seeing, and working with the ever-present dynamic forces of change and the new?

Their general method in this book is two-fold: 1. perspectival contrasts of processes of stabilizing and transforming, and 2. new images of these practices. And this introductory plateau presents perhaps their most famous contrast and new image of practice: the rhizome.

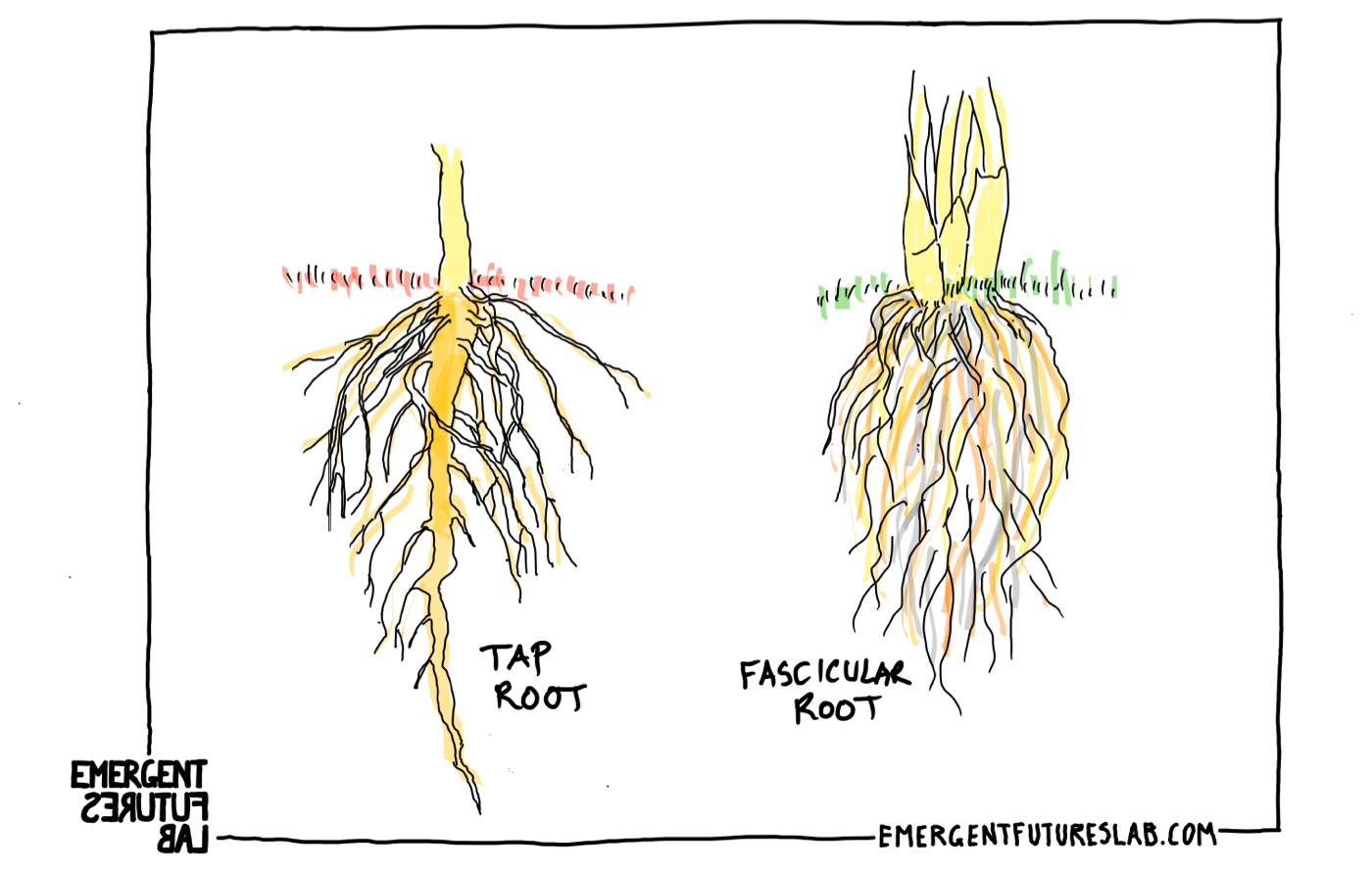

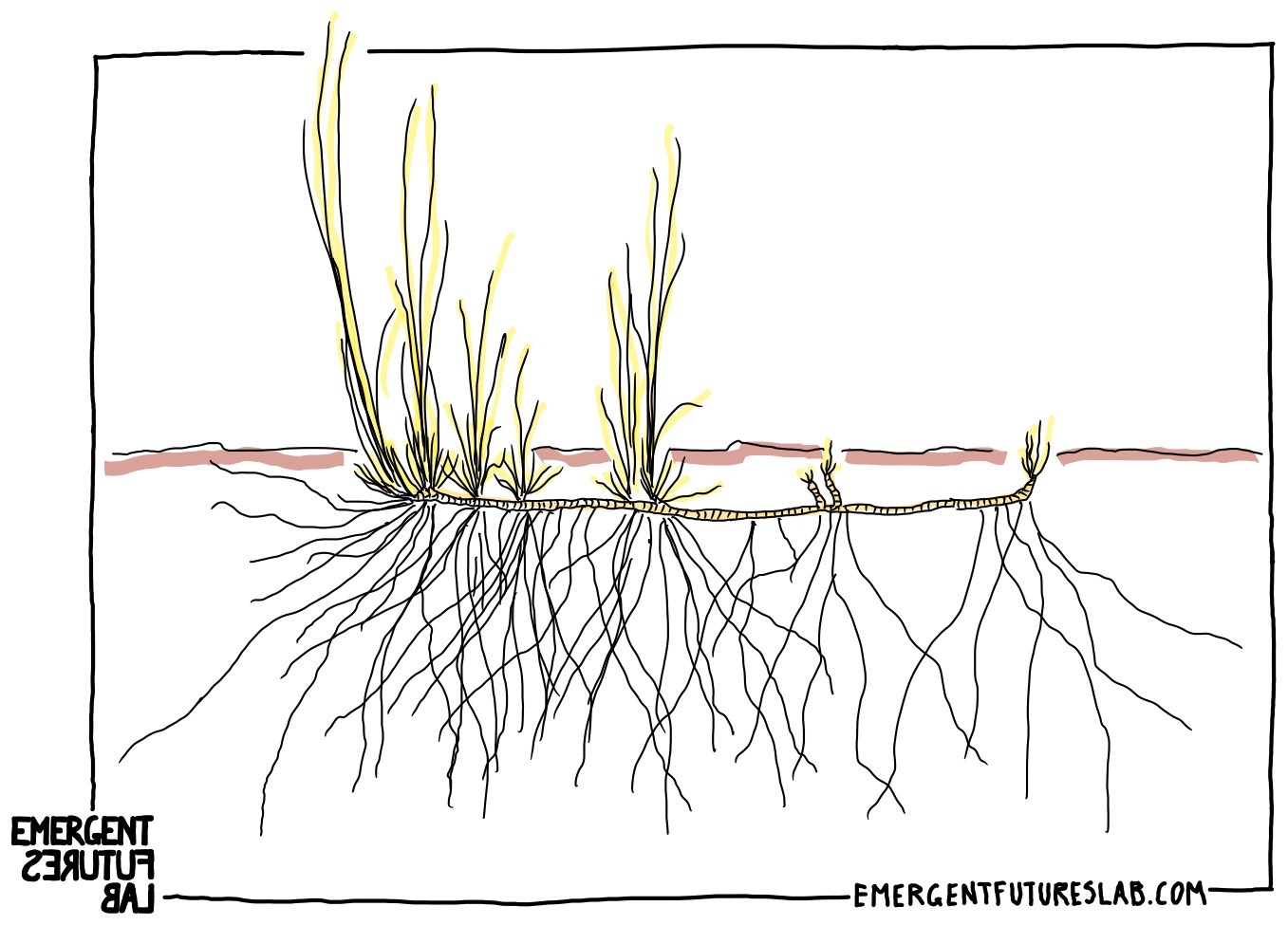

Right off the bat, they are presenting us with a novel image of the book as a type of root and tree. We are presented with the tap roots, fascicular roots, and “tree-books”.

Why roots? Why trees? Roots lie hidden beneath in the soil and give rise to visible things – trees, plants, flowers, bushes, and weeds. Simply put: Roots give us one image of the creative processes of becoming.

And roots and trees are everywhere in the habitual historical descriptions of creative processes:

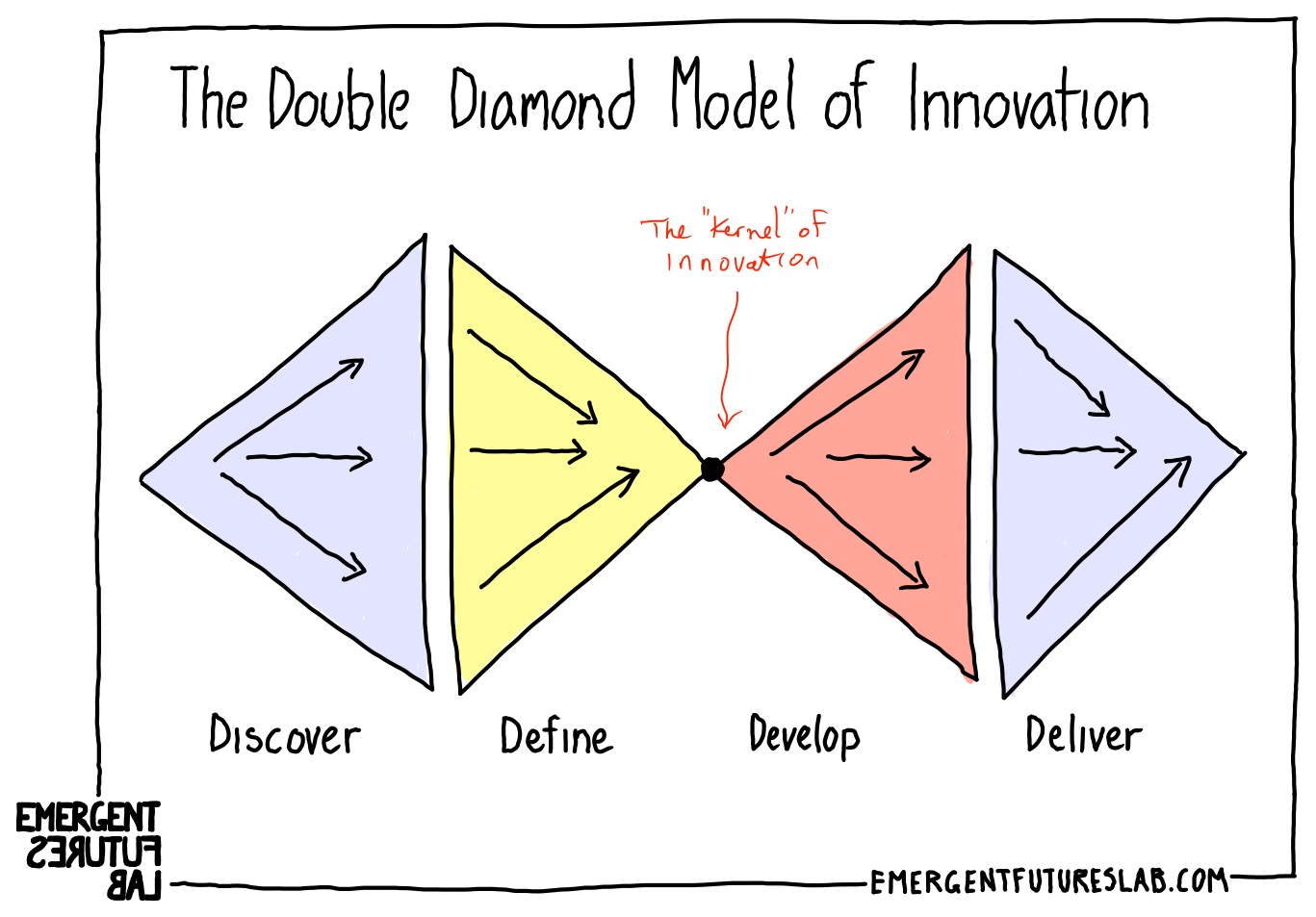

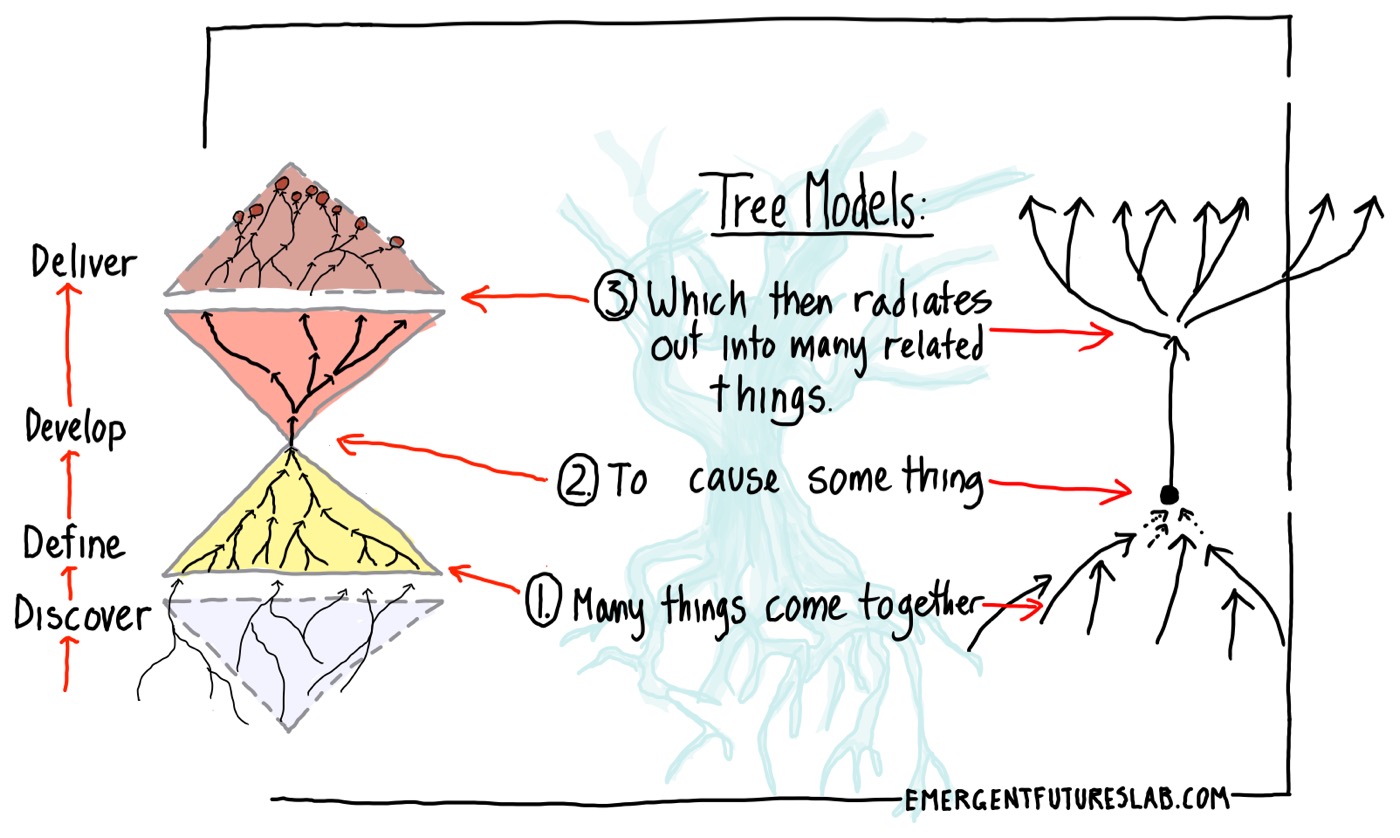

Perhaps the most famous of these tree diagrams of a creative process is the “Double Diamond” (which is also one of the most ubiquitous and problematic images of a creative process):

How are these diamonds a tree? We just need to turn it on its side to see this:

/

What is the issue with the tree model of creativity? For Deleuze and Guattari, this tree logic is a process by which imitation, representation, and reflection work – where the many novel differences are forced to become one and then forever reflect the one. What is the problem with this process? It is a process not of creativity but of forcing differences to correspond to a tacit pregiven assumption that underneath all of the surface differences is sameness – a common essence: The many become one and then one becomes the many as only variation in degree.

The double diamond, like so many purported creative processes, is in fact an anti-creative process unconsciously designed to produce imitation. Here, Deleuze and Guattari do not critique it as evil and wrong – rather, it is unhelpful if our goal is to engage with creative processes. Trees are what they see as “over-coding” processes of producing sameness.

So what is an alternative way to engage with creative processes? Here they offer a very helpful contrast: the Rhizomatic root rather than the aboraceous root (tree root). Rhizomes are also rooting processes, but they do not converge on a single plant stem or tree trunk – rather, they can infinitely diverge, wander, and multiply plants and trees. Rhizomic plants have no center, no single source, nor final form:

The examples are vast: corn, dandelions, bulbs, tubers, mushrooms, and some trees (the aspen) are all rhizomes. And to this they add rats, packs, and even their burrows.

Here we have a new image of an open-ended, relational, and ever-changing creative process, which they define as:

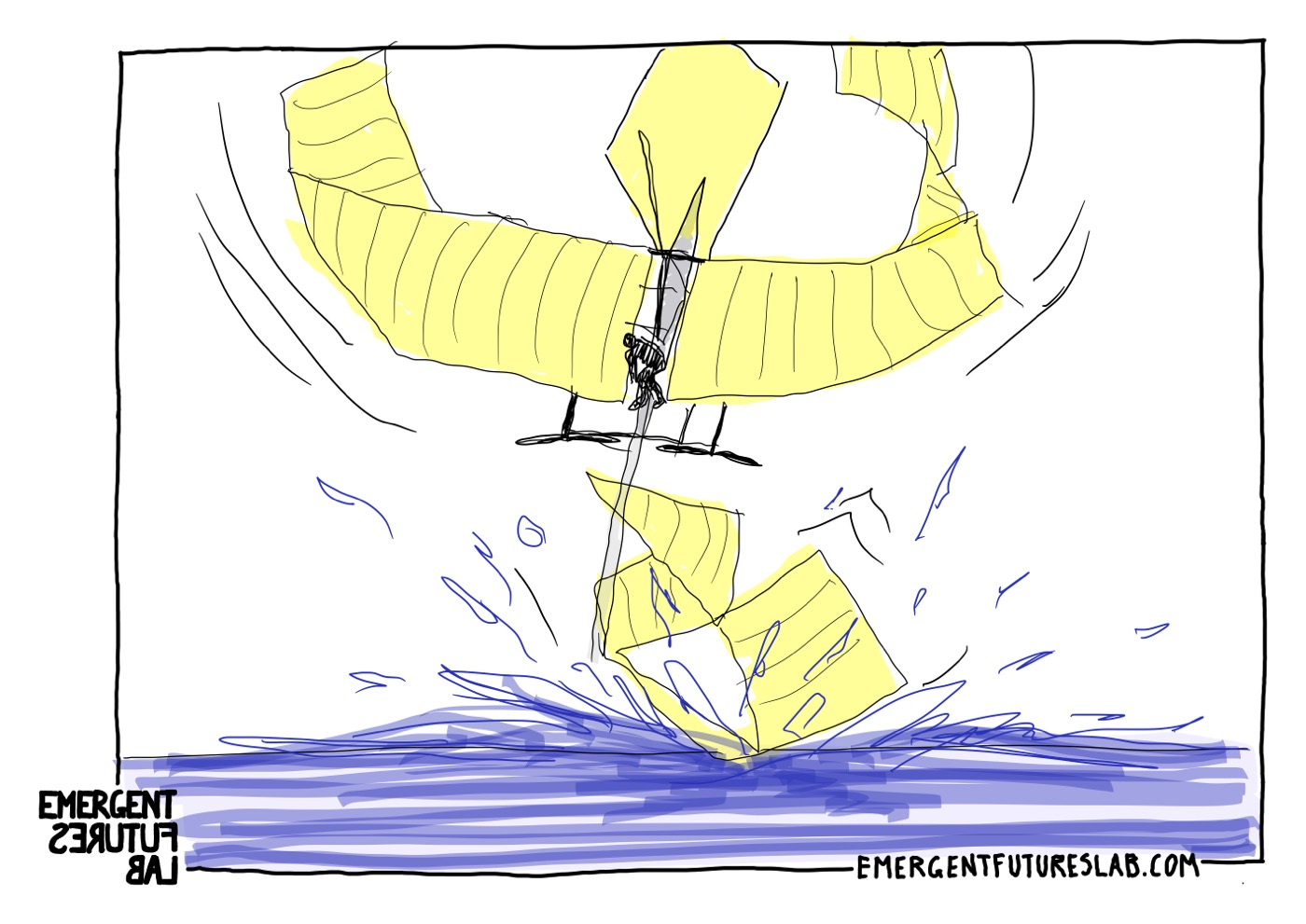

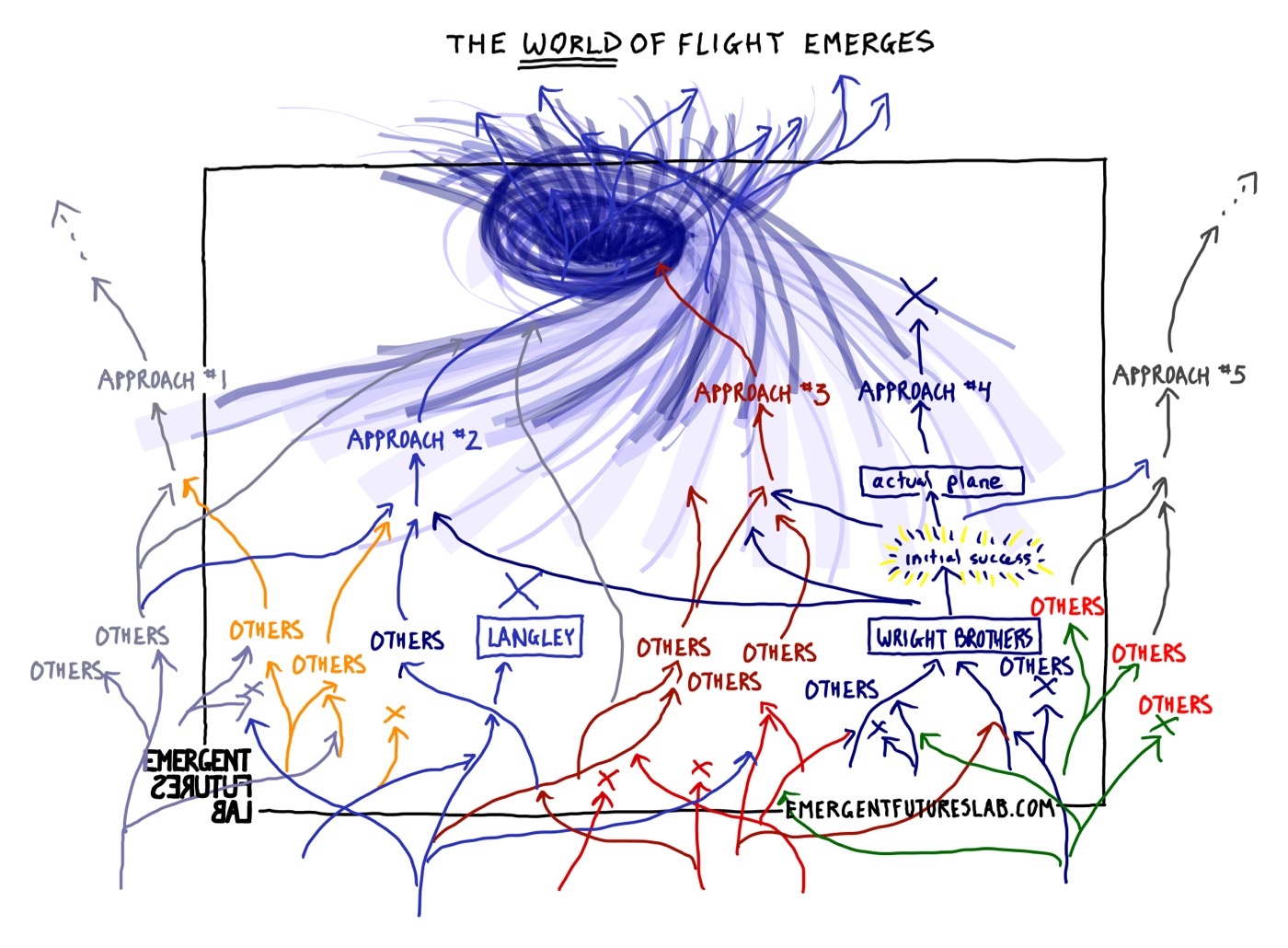

Now this can sound very abstract, but if we take the invention of human flight as a test case, we can see something far more rhizomatic than tree-like occurred:

Rather than experiments branching out and then converging on one successful strategy – say of the Wright Brothers (as the double diamond/arborescent model would suggest). With a careful exploration of the history see that there was a broad field of variously connected researchers, processes, environments, tools, weather systems, and non-humans from which emerged a multiplicity of approaches. Some of which succeeded, others did not directly (but parts were incorporated into other successful approaches). And early successful approaches (like the Wright Brothers) eventually were abandoned… And approaches that failed were rediscovered and appropriated in successful ways. Tangential practices of all kinds were incorporated (new forms of asphalt, vulcanization, the extrusion of wires, advertising, etc.) to give rise via emergent processes to a semi-stable ecosystem of our modern aviation industry.

[Note: For examples of Rhizomatic logics in creative processes in an organizational and brain contexts, see newsletter 196]

And lest we narrowly understand the concept of the rhizome by directly drawing only from existing plants, they remind us that the rhizome must be made – it cannot be simply found.

And how do we make a rhizome?

Here, they offer an astonishingly simple and powerful method for engaging with creative processes in the context of habitual overcoding (which is our most common context).

How? Subtraction.

Refuse and remove any totalizing structure. Which they explain with a simple formula: n - 1.

What does this look like in practice? Let's take our chair example from earlier: simply refuse and remove the reductive overcoding of the predetermined and fixed identity and purpose from the actual physical chair. Now it signifies nothing but awaits rhizomatic relational experiments.

To the question “What is this?” answer: “I don’t know – let’s see all that it can do!” And as we concretely and experimentally do this work we make a rhizome.

Obviously, with the chair – we do know what it “is” – but this structure of definition and solidification of singular purpose cannot account for what it might become if we could connect any and all parts of this chair to other things and practices where the possibility of qualitative change that exceeds the knowable is always present. And this is what this method of n-1 does.

We have to have new images of practices and new contrasts that we can experiment with: Trees and Rhizomes. On page 21, Deleuze and Guattari summarize the principal characteristics of a rhizome – and this is worth reading closely.

Then they end this plateau with this wonderful reminder:

A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo. The tree is filiation, but the rhizome is alliance, uniquely alliance. The tree imposes the verb "to be," but the fabric of the rhizome is the conjunction, "and…and… and…" This conjunction carries enough force to shake and uproot the verb "to be."

Where are you going? Where are you coming from? What are you heading for? These are totally useless questions. Making a clean slate, starting or beginning again from ground zero, seeking a beginning or a foundation—all imply a false conception of voyage and movement (a conception that is methodical, pedagogical, initiatory, symbolic...).

But [there is] another way of traveling and moving: proceeding from the middle, through the middle, coming and going rather than starting and finishing… move between things, establish a logic of the AND, overthrow ontology, do away with foundations, nullify endings and beginnings… know how to practice pragmatics.

The middle is by no means an average; on the contrary, it is where things pick up speed. Between things does not designate a localizable relation going from one thing to the other and back again, but a perpendicular direction, a transversal movement that sweeps one and the other away, a stream without beginning or end that undermines its banks and picks up speed in the middle.

A Thousand Plateaus goes on to multiply the list of creative contrasts – all the while giving more and more novel images of creative processes and stabilizing processes.

We suggested reading two other plateaus (The War Machine and The Smooth and The Striated) because in these two plateaus, they experiment with creative processes that exceed and even refuse identity. Which is something critical for a radically creative practice, because if the radically new is indeed totally new, it will necessarily exceed and indeed rupture existing identities. When something qualitatively new emerges, it will emerge in an asignifying manner: there will be no words or images for it, and to bring in words and images too quickly would be to overcode novel differences with the known and the given. But working at the edge of ideas and concepts is perplexing, counter-intuitive, and little explored in our idea and identity-centric approaches to creativity. These two plateaus do this work of developing an approach that goes beyond ideational imposition towards an asignifying creative experimentation.

In this week's newsletter, we will not even try to make an effort to do justice to the richness of these two sections of A Thousand Plateaus – we have already gone too long into the night writing. The rains have come and gone. The moon has set. And the city has gone quite outside the open windows. It is time for a nap.

But these pages contain some of the most beautiful writing on how to follow the new experimentally rather than imagining we can impose our ideas on seemingly inert matter willy nilly after a good brainstorming session (see pages 361-374, and 403-423 especially).

And finally, in The Smooth and The Striated, we find an astonishing proliferation of creative models:

All giving us experimental ways into the conjoined creative logic of smoothing (going towards n-1) and then stabilizing the new (striation).

They end this final plateau fittingly for a book that champions a radically experimental world and all-encompassing creativity with a caution:

“Never believe that a smooth space will suffice to save us.”

And here too we leave you. Keep smoothing and striating, following, perturbing, connecting, refusing, stabilizing, and, and,

– and keeping, all the while, difference alive.

And, let’s all keep reading this wonderful book, and we will come back to it in the newsletter as the winter snows begin to blanket this region.

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.