WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 212! Creativity – Never “One and Done”...

Good morning to those who follow accidents cyclically to alternative horizons,

It’s week four of our series on blocking, and we have been going slow to go well. In the previous three weeks, we have been looking at what one could reasonably understand to come before the “act” of blocking (Volumes 209, 210, 211). But neither we nor creativity are “reasonable”! And for us, this is no singular act or action with a neat before and after. Before getting into this critical thicket of things, let's stick with what might be thought of as a reasonable summary of the journey so far:

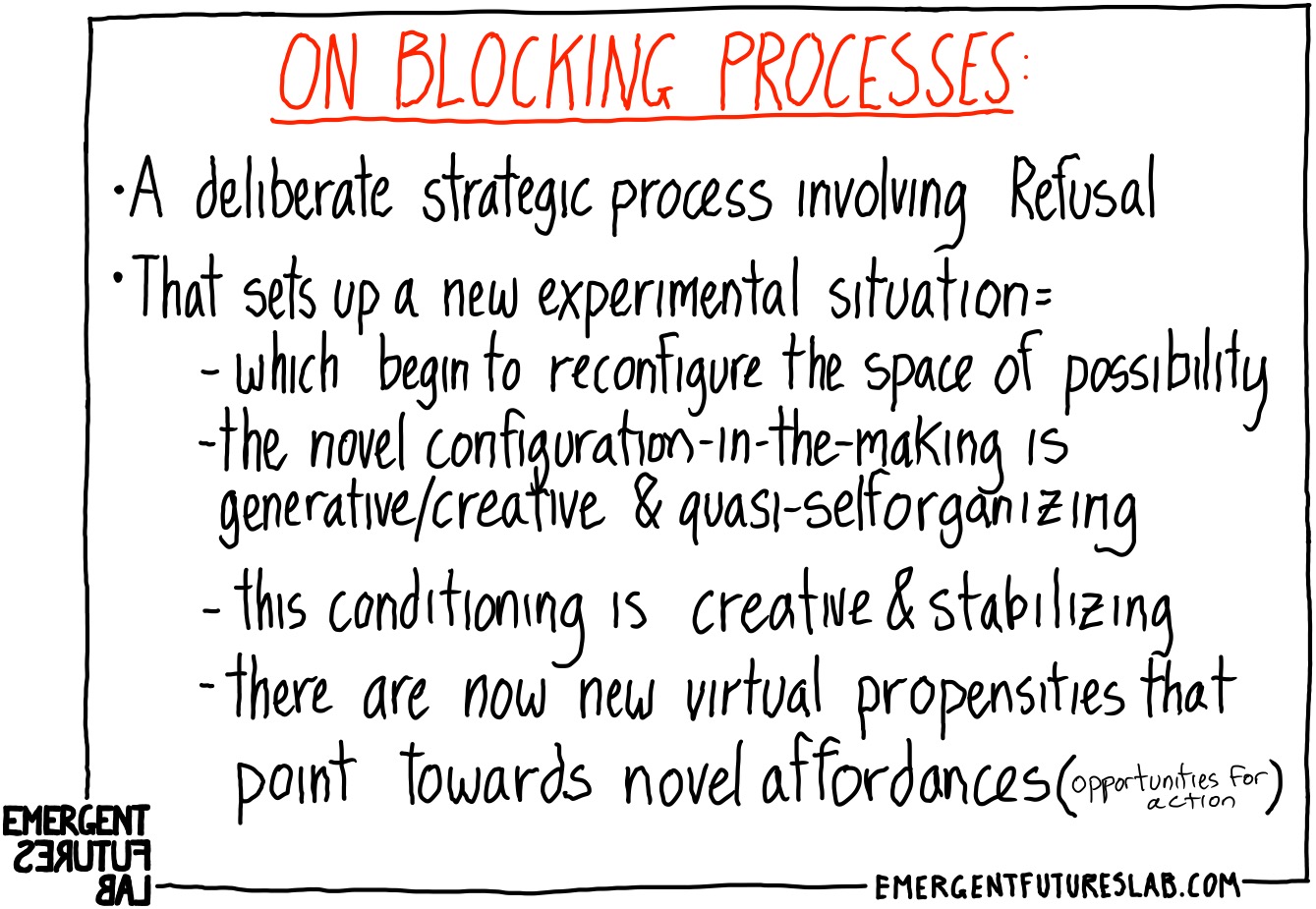

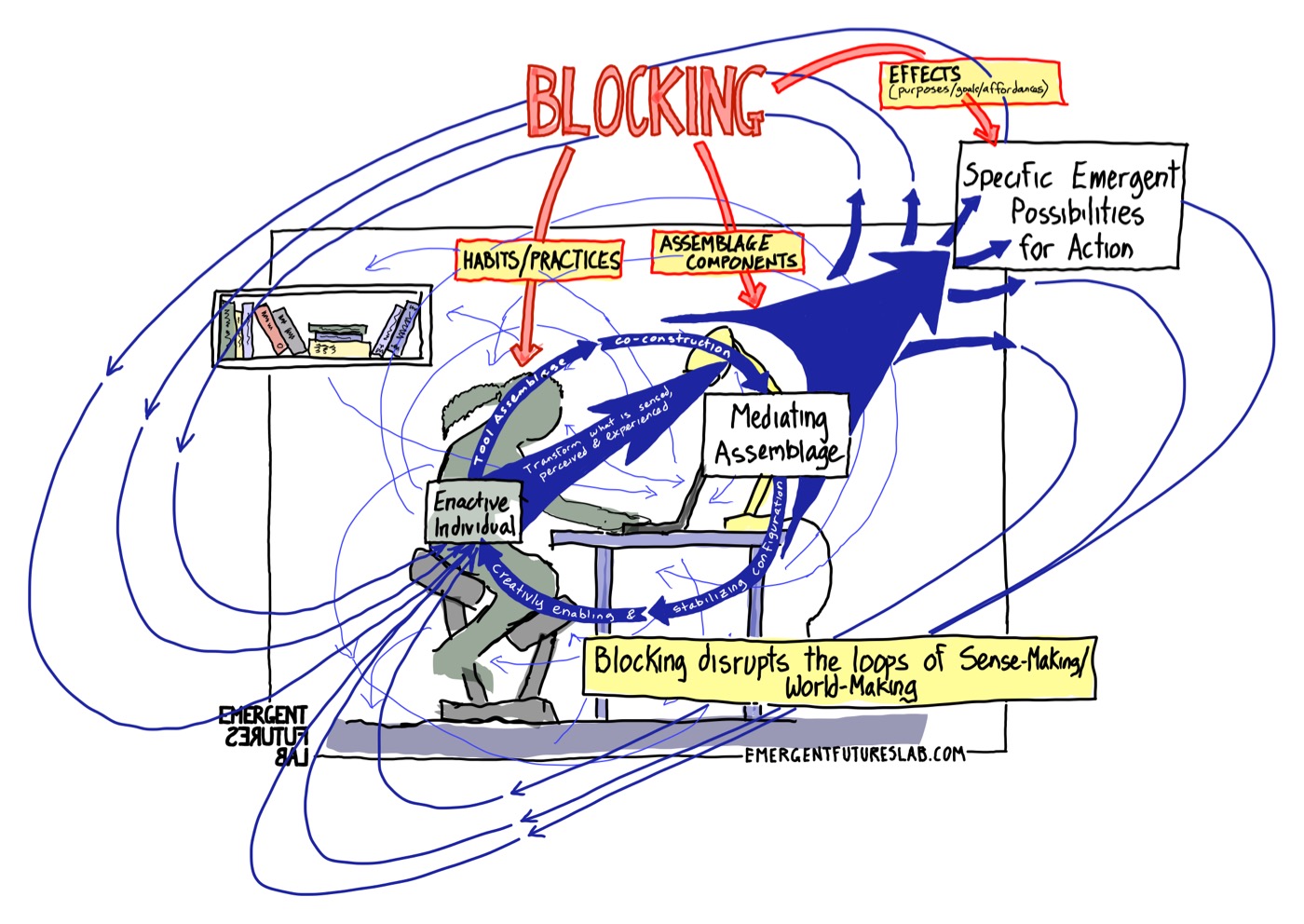

Blocking involves a deliberate strategic refusal that works with the disconnecting of things and purposes:

This relational disruption begins a reconfiguration of the space of possibilities such that new opportunities for action become available:

And these practices are premised on a clear logic: we cannot do something new if we first do not engage and disclose the logic of what exists and then block it in a way that opens us up to something genuinely new.

These early aspects of the processes involved in blocking have been the focus of the last three newsletters.

But – here's the thing that always happens to us – the moment we say “Creativity” or “Blocking” in a discussion or workshop setting, many people's spontaneous reaction is to immediately understand this as a discrete act. We have experienced this with great frequency over the years, which suggests to us that it is something other than simply a personal response – it is part of a set of historically grounded tacit cultural habits.

When we bring up creativity, most descriptive responses involve imagining that it happens in a singular instant – a flash. When we ask follow-up questions about the before and after – no one denies this – obviously, there is some build-up and some follow-through – but creativity is this decisive moment:

And it is equally true when we bring up blocking as a type of creative process – most people respond in a way that makes it clear that they understand it as a singular act. There is a before, the moment, and an after:

For many, there is a neat symmetry in these seven steps – the three before blocking are preparation – the before (1-3 above), then the blocking is the decisive moment (#4 above) – and then three more steps follow after (5-7 above).

Perhaps the most famous historical story that is contemporarily used to both illustrate and argue for creativity as a solitary act is the apocryphal story of the classical Greek philosopher Archemedies contemplating the problem of whether the king's crown was actually made of gold or mixed with some metal of a lesser value. In this story arc, we find our philosopher stumped and taking a bath. While taking a bath, he has a flash of insight and jumps out of the bath, crying out, “I have found it!” (eureka). And then proceeds to carry out his new approach to measuring differing displacements.

Now it is unlikely that this is a true story or one that, if it were true, would involve Archimedes imagining it as having anything to do with creativity. As many a historian of Western creativity will tell you, to make any Western cultural artifact before the mid-1800s a story about human creativity is entirely anachronistic. But that is a tangent to follow another time.

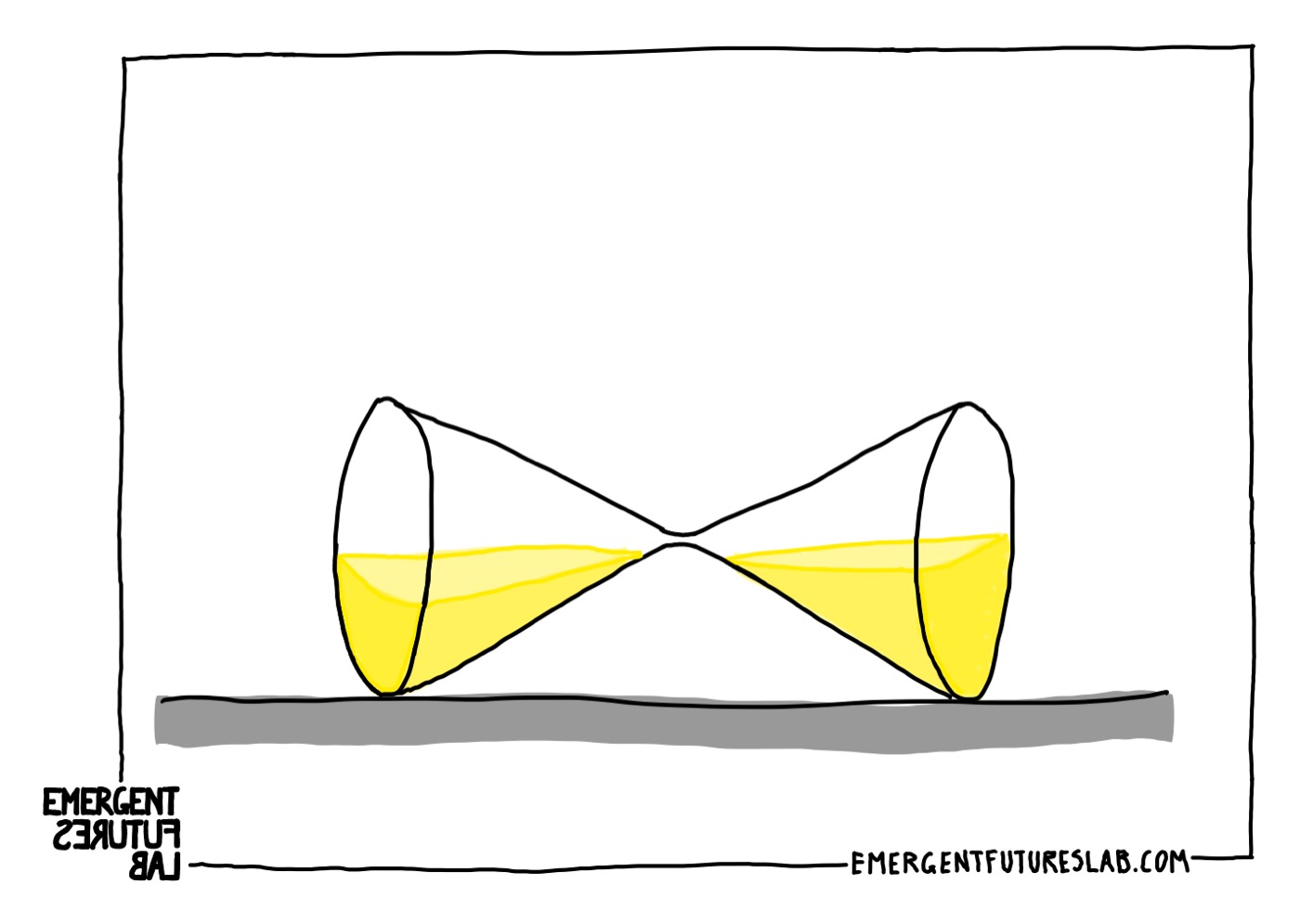

In the contemporary retelling of this Eureka Story, we have all of the elements that have come to define the modern approach to creativity: some conditions lead to a decisive moment, and then everything follows. It is a pattern – that of the overturned hourglass – that we see repeated widely across creative methodologies from Design Thinking to the Double Diamond and beyond:

This is a logic that pivots on a moment: a “Decisive Moment”, an “Ah-Ha” moment, a Eureka Moment – an instantaneous epiphany in which everything coalesces and the novel creative idea is revealed.

Before this is a great struggle, doubt, frustration, work, experimentation, and uncertainty. And after this, there is great clarity, a sense of purpose, and mission.

The key concept in this logic is that there are many processes before and many processes after, but this is the moment, an instant in which everything coalesces and transforms into the germ of the new.

It is a tripartite logic that carries over into many of our culture's habitual approaches to most creative practices, whether in researched biographies or in moments of the self-reporting of those involved in innovation activities.

Our question, when confronted by what could be best understood to be a well-established storytelling trope, is always threefold: how did we come up with this logic as our way of framing and understanding creative events? Is this approach useful? And what is its truth in this specific context?

With the development of a careful scholarship of innovation, we know that there is no truth to the use of this narrative structure. Let's indulge in one example. This is from the author's preface in an exceptional book on innovation processes, The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger by Marc Levinson:

“Many aspects of the response to The Box were startling, but perhaps the most unexpected concerns a widespread stereotype about innovation. In his later years, Malcom McLean, the former trucker whose audacious scheme to create the first containership line is recounted in chapter 3, was frequently asked how he came up with the idea of the container. He responded with a tale about how, after spending hours in late 1937 queuing at a Jersey City pier to unload his truck, he realized that it would be quicker simply to hoist the entire truck body on board. From this incident, we are meant to believe, came his decision eighteen years later to buy a war-surplus tanker and equip it to carry 33-foot-long containers.

The story of this "Aha!" moment does not appear in The Box, because I believe the event never occurred There is certainly no contemporaneous evidence for it. I suspect that the story of McLean's stroke of genius took on a life of its own as, decades later, well-meaning people asked McLean where the container came from.

As I show in chapter 2, ship lines and railroads had been experimenting with containers for a half century before Malcom McLean's trip to Jersey City, and containers were already in wide use in North America and Europe when McLean's first ship set sail in 1956.”

The processes involved in innovation are far more distributed, collaborative, materially engaged, complex, patchy, contingent, transversal, durational, punctuated, configurational, quasi-self-organizing, and emergent. But this is both a story for another time and something we have covered in great depth elsewhere (Volume 202 gives a great overview of this).

Understanding the long history of why almost all of our creativity stories share the same mythic narrative structure would take us back to the Greeks of the sixth century before the common era (who believed that they were being granted insight by the muses into fixed universal truths in their moments of inspiration). And it would follow a long and complex set of contingencies into the present (we detail this history in Volume 27).

Understanding how and why things come about is hard precisely because, in their emergence, they destroy the evidence of their own formation. This leads to forms of storytelling that are backcasting – with the tacit belief that there must have been some kernel of what exists now at the beginning; the linearization of vast, complex, and contingent processes; the focus on discreet agential actors; and a neat story arch of a before, then a magical moment and how it all neatly and inevitably unfolds afterwards.

We believe that much of the preparation to engage with creative processes should involve the careful and critical study of literary forms – how we tell stories – so as to recognize when our attentional activity is being pre-shaped by an irrelevant and distracting form.

But stories don’t exist independent of a complex of embodied and enactive collective practices of living and world-making. Paying attention to stories is also paying attention to collective practices, habits, concepts, tools, and environments, and their styles of individuation and meaning-making. The blocking practices of creativity will involve the blocking of narrative tropes and their related practices, habits, concepts, tools, and environments.

The ubiquity of this problematic approach becomes really clear when we get into the practices of blocking.

Obviously, we are not by any means alone in our interest in the importance of negative techniques and practices for creativity. Blocking has been developed and refined in many creative practices from the arts (in the production of negative rules as generators of creativity (e.g., Olipo, Fluxus, John Cage, etc.) to Sports and Games of all sorts.

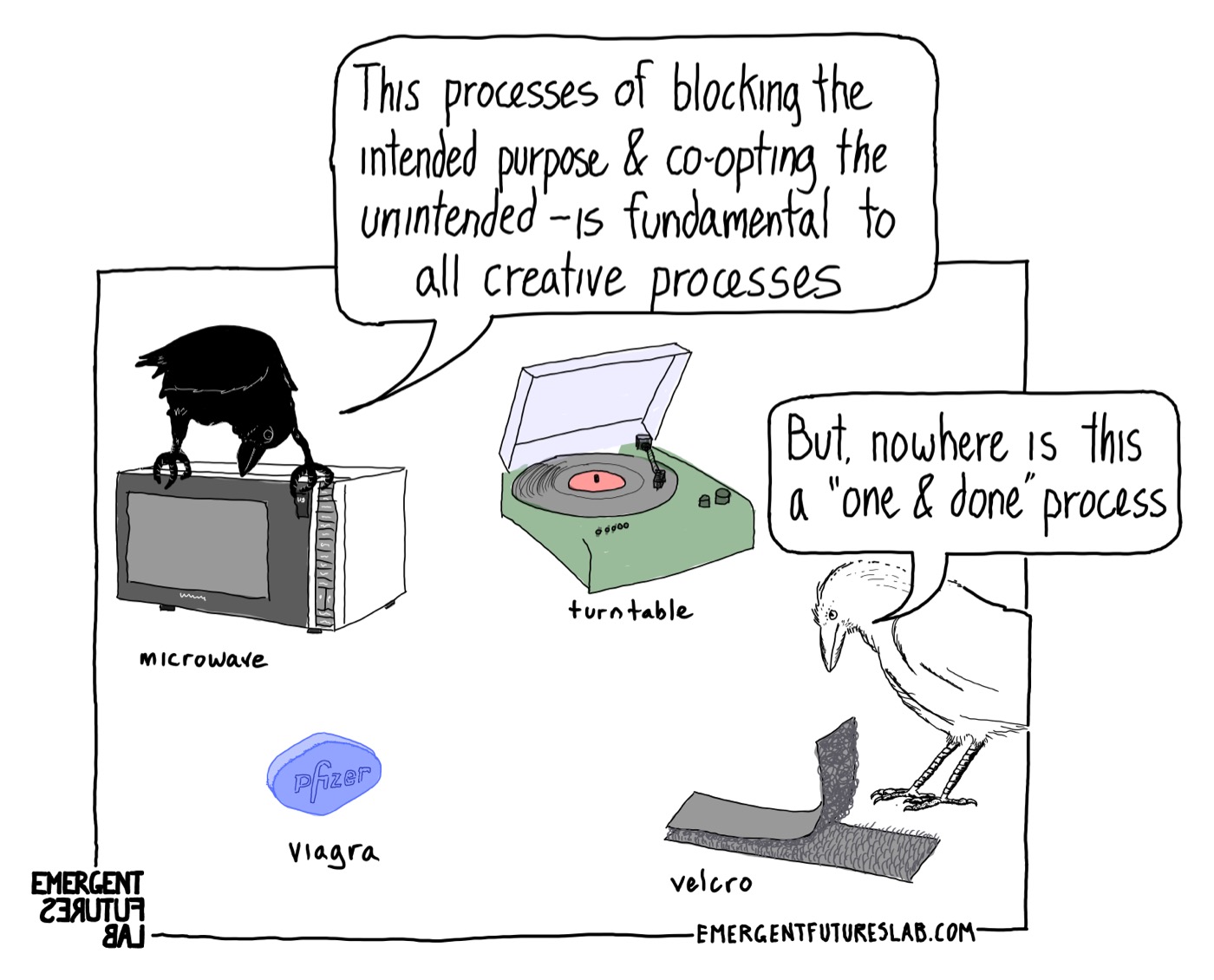

One area that has drawn a huge interest in the power of blocking is the many areas of business that have been researched in the evolutionary processes of exaptation. (These are the processes by which something that has evolved for one function is co-opted for a new and unintended function.) And this interest is for good reason – research has shown that exaptive processes play a significant role in all human innovations (we have spent an inordinate time investigating and experimenting with the topic of exaptations – this link will take you to some of our research).

In fact, just today, we came across a really interesting article on how the birth of the Iron Age emerged via a series of unintended exaptations of both the copper mining and smelting processes.

The processes of Exaptation and processes of Blocking are closely associated: we would argue that we can understand the process of exaptation as a form of the blocking process: “block the intended use of anything – and then experiment with what else it can do.”

But – here again, the storytelling tropes of the tripartite decisive moment approach are to be found.

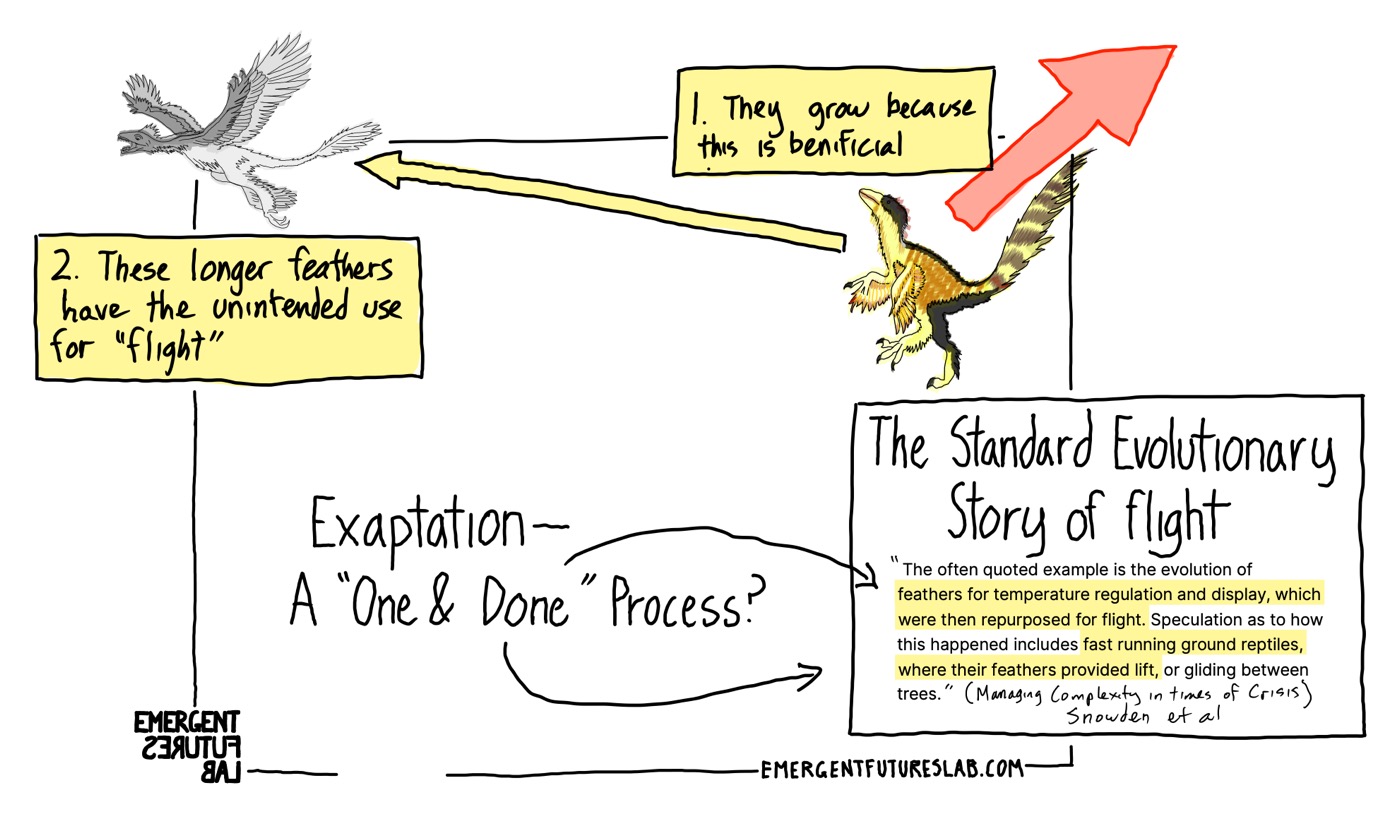

Let's take a minute to look at how exaptation is described and framed by business consultants. By far the most cited example of exaptation in the world of business consultants is the exaptive process involved in dinosaurs becoming birds (it makes for a compelling story and one that we also use amongst others). Just using a basic Google search, we come across this now quite standard example and the equally standard approach to presenting the process:

“The often quoted example is the evolution of feathers for temperature regulation and display, which were then repurposed for flight. Speculation as to how this happened includes fast running ground reptiles, where their feathers provided lift, or gliding between trees”. (Managing Complexity in Times of Crisis, Snowden et al.)

This makes for a compelling, provocative, and easily understood three-part story:

Now you might recognize this particular form of storytelling as our tipped hourglass of the decisive moment. And one that, at least from an evolutionary perspective, is both a profound mischaracterization of the processes involved, and skips over the what and why evolution in general is so astonishingly creative.

(Just as an aside about purposes and perspectives: obviously, from a business perspective, if the goal is to introduce a simple technique of co-opting and repurposing into the mix, then there is no compelling reason to get things correct at any deeper level from an evolutionary perspective. If it is only about developing a simple pragmatic tool for incremental creativity, then this view of exaptation as a one and done process that is focused on discreet material things is more than just fine).

The problem that we wish to focus on this week (and next) in terms of innovation processes is the characterization of them in this tripartite decisive moment storytelling logic as being “one and done”.

What do we mean by “one and done”? In all these cases – from Archimedes' exclamation of “Eureka!” to the retelling of the first dinosaur-becoming-bird flight it is always cast as a type of before and after of an instantaneous act. Of course, there is a lot that happens before and much that still needs to happen after, but once the idea happens or the first dinosaur lifts off while running – the rest is history as they say…

But – you may sensibly ask:

“What about iteration? Aren’t you making a type of “straw-man” argument? Don’t the more fully developed versions of Design Thinking and The Double Diamond stress iteration? Don’t most of these approaches explicitly state that they are not one-and-done? And aren’t most contemporary models of innovation iterative and loopy? Doesn’t this ubiquitous stress on iterative repetition by most approaches not make it a linear one-and-done process?”

It is indeed true that the processes of iteration are explicitly stated by the more developed versions of these practices as being critical to the process. Iteration and iterative feedback loops are part of these practices, and they are no doubt important (and also effective). But the question is one of goals – what is this form of looping effective at?

What is the goal of iteration?

It is a feedback process for testing and refinement. The loopings of iteration in the Double Diamond are ones that test each stage: Did we do it well? How should we refine and improve what we have done? And this repeats until there is satisfaction with the answers. Here, iteration is a part of an ultimately linear process for refinement and improvement – not a process for the generation of genuine emergent novelty.

We see this most clearly in the contemporary definition of the term:

“A repetition of a… procedure applied to the result of a previous application, typically as a means of obtaining successively closer approximations to the solution of a problem”.

This is even clearer in how exaptation is presented: there are lots of iterations – variations in feathers, one of which leads to a dinosaur capable of running to produce lift. And then there are lots of variations after this exaptive moment to refine and “adapt” this set of creatures to take full advantage of their possibilities for flight.

In all these cases – that of Design Thinking, the Double Diamond, and the standard business consultant story of exaptation – iteration in no way changes the basic logic of the problematic “one and done” logic of the decisive moment approach to creativity, innovation, and blocking. In fact, iteration reinforces this focus on getting the decisive moment right.

While we have discussed how this approach to creativity and blocking is problematic in terms of these processes being “far more distributed, collaborative, materially engaged, complex, patchy, contingent, transversal, durational, punctuated, configurational, quasi-selforganizing and emergent”. There is an even more basic and profound reason why this approach is so profoundly wrong. And this is both critical to doing the processes of blocking well and understanding exaptation properly – and this is their cyclical nature.

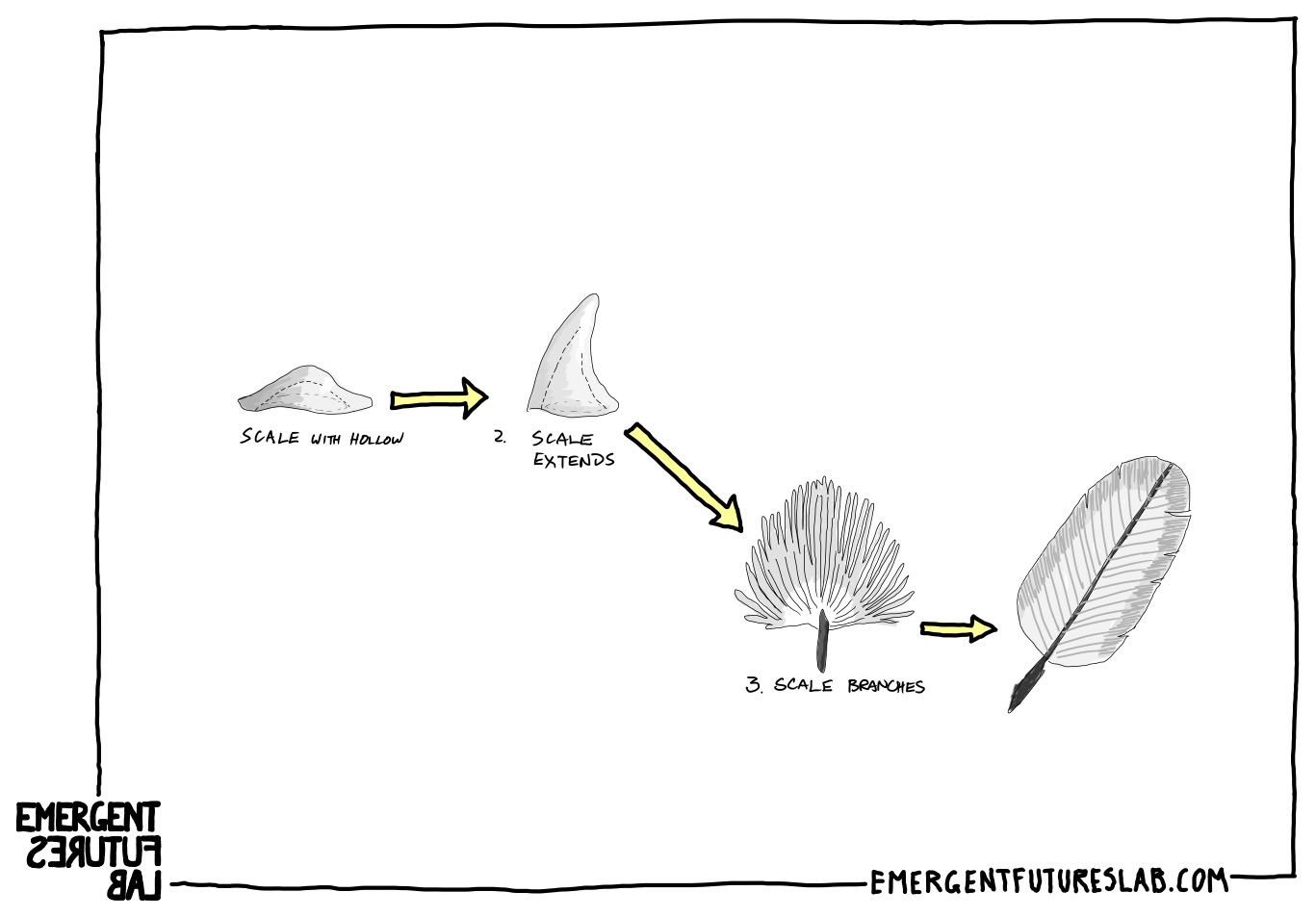

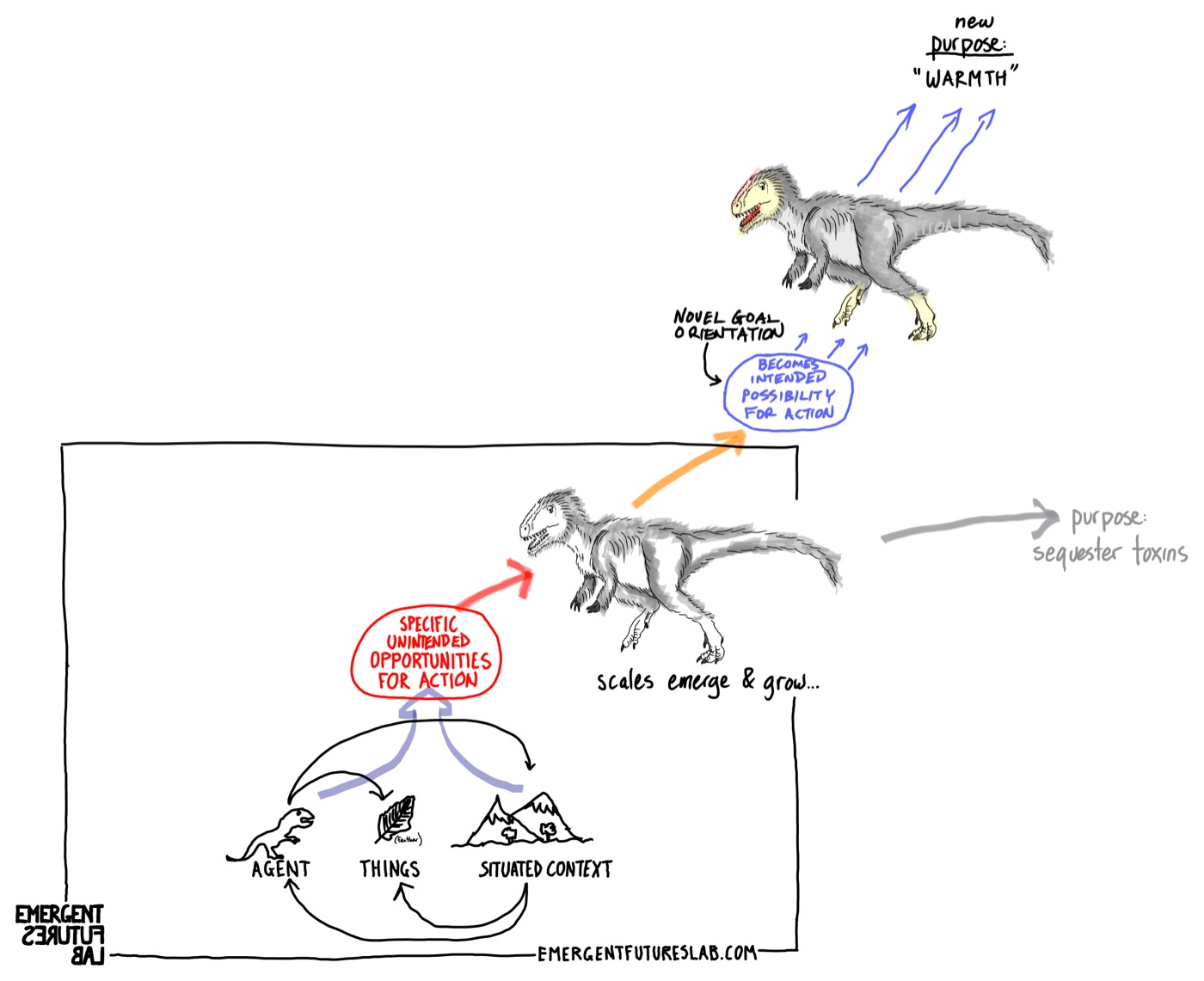

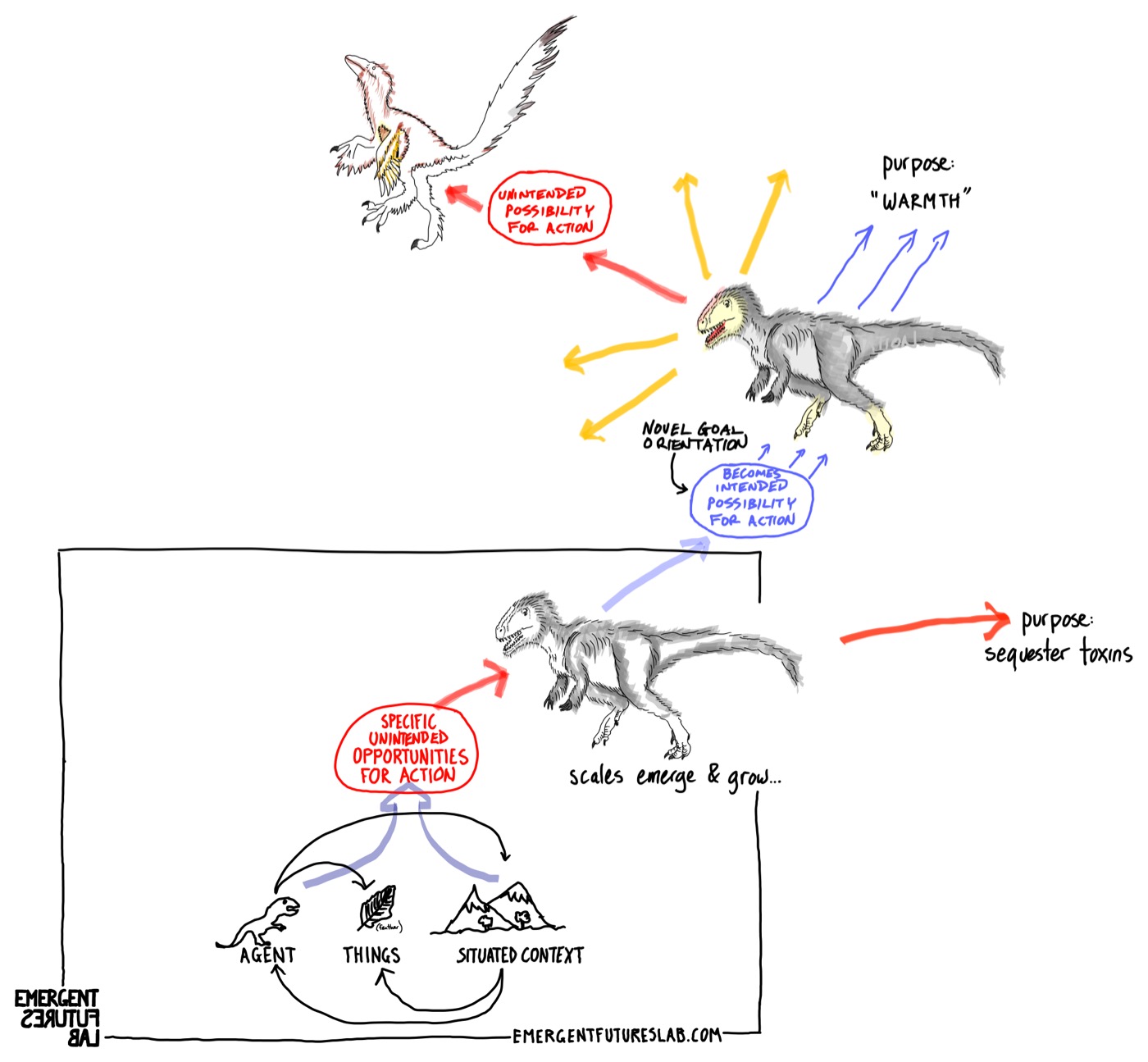

To get a sense of this form of looping and how different it is from iteration, we need to pick up the story of dinosaurs in the midst of their ongoing life. This is an active and embedded life that is, at every moment, involves both stabilizing tendencies (so-called adaptations) and novel tendencies (so-called exaptations). At the moment we meet our dinosaur friends, some dinosaurs are developing scales (which, early on, played an important role in sequestering toxins).

Being effective in sequestering toxins, the scales enlarge, bend, and shift into a three-dimensional form – what in retrospect we would call a proto-hair or proto-feather.

This scale and scale-proto-feather in the context of dinosaur life provides many opportunities for action (affordances), including and beyond sequestering toxins. One prominent affordance of a small hollow micro tube is encapsulating warm air (e.g., insulation):

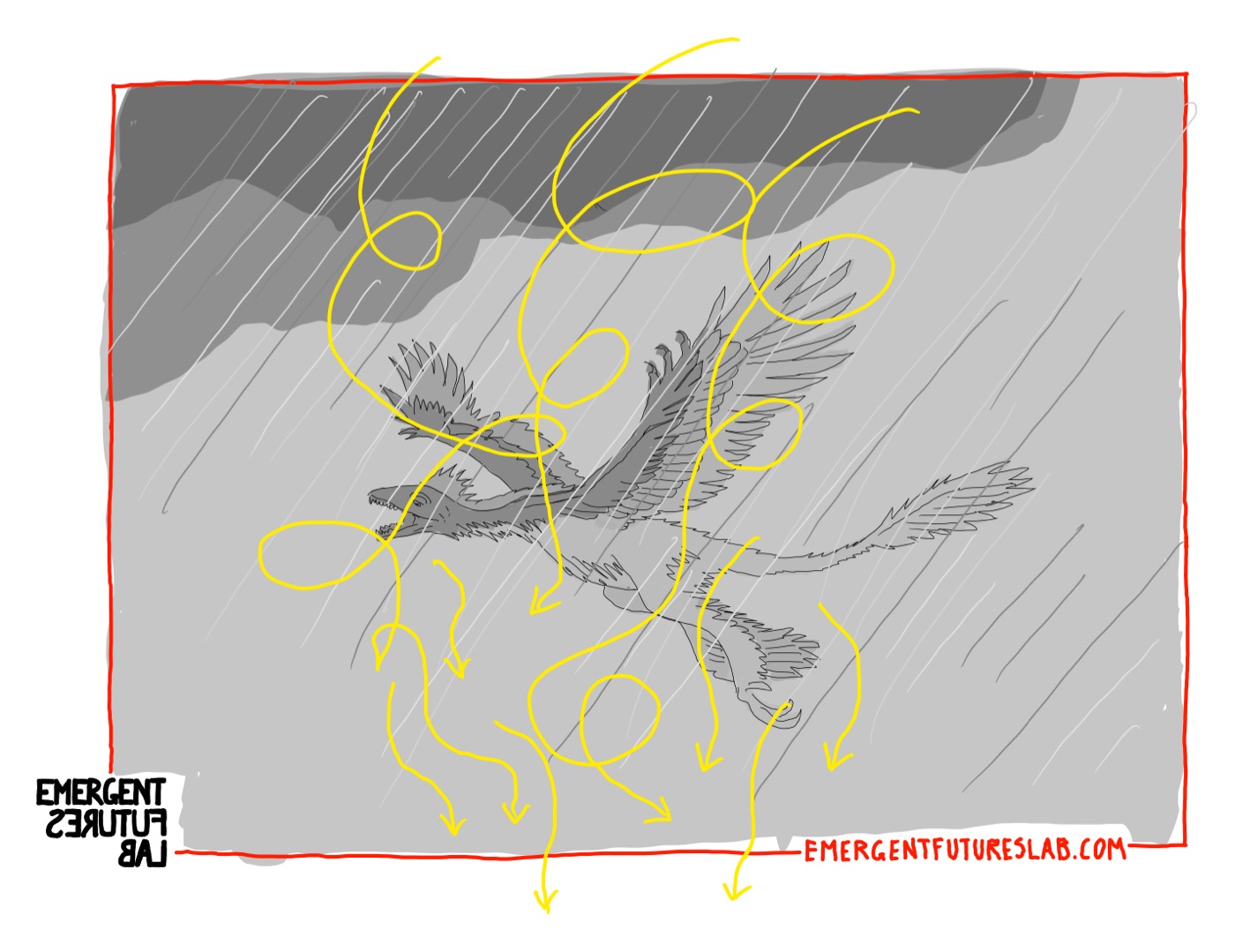

This novel affordance stabilizes as an additional “purpose” and a potential deviation in morphogenetic possibilities: scales can go in many directions, and one potentially leads in a qualitatively new direction: a generally “feathery” direction. Here we already have many cycles upon cycles of diverse variation where there is never a clear distinction between what is an exaptation and what is an adaptation – all that matters is that living persists (nor is it ever clear that we could even specify that one thing has one purpose).

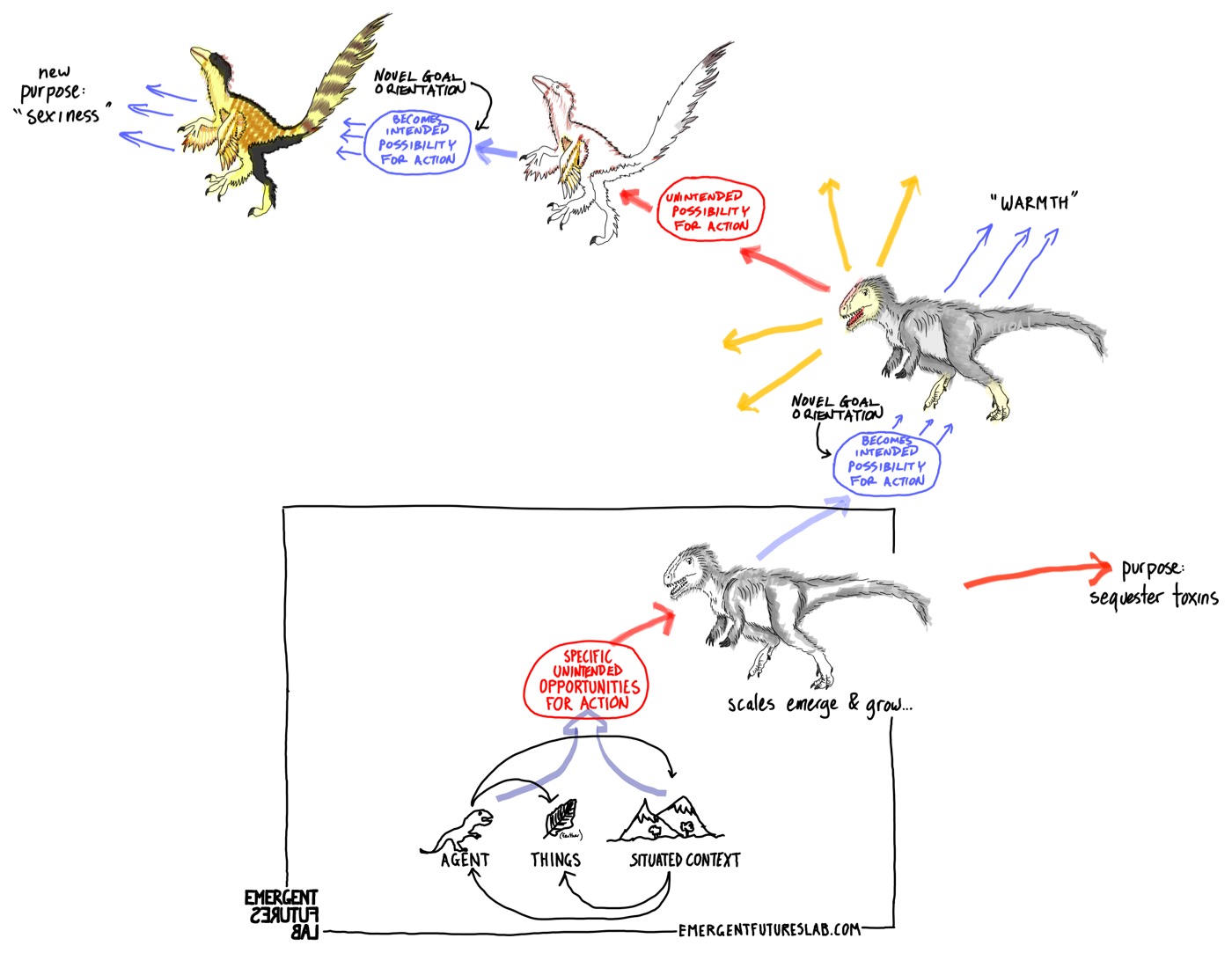

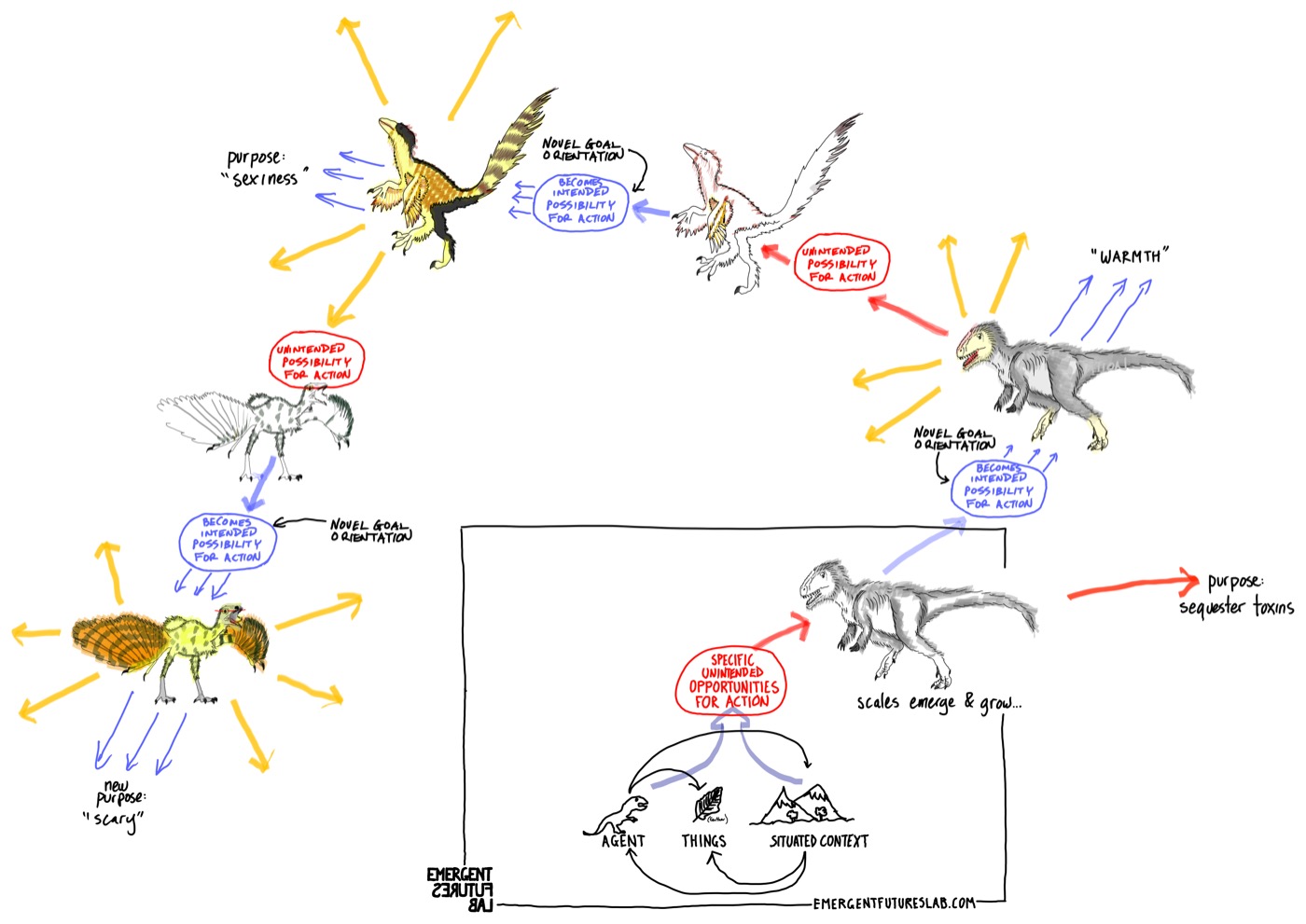

These proto-feathers diversify and enlarge as their variations participate in testing out the boundaries of the vast space of affordances for warmth. Being hollow tubes, there is the ever-present potentiality of being “filled”. And via chance variation, some are filled – proto-pigmentation emerges (an exaptation). Now a novel cycle emerges: pigmentation for sexual selection.

This cycle stabilizes in ways that allow for the cyclical exploration of colored feathers and their possibilities. Longer colored feathers develop in all sorts of places and patterns where they do not impede other functions (perhaps primarily movement):

Hopefully, the logic of this process is becoming clear – these cycles are not iterations, and there is no decisive moment. Diversification and stabilization repeat and multiply and cross-pollinate – without end.

We write of these cycles in our blocking process as the repeating of six of the seven steps in the process (steps 2-6 below):

The Blocking Process (the simple version):

The key step in this cycle that allows qualitative differences to emerge is number six: “stabilize these novel effects into a new design”. And then we can repeat the total cycle of engaging, disclosing, blocking, deviating, and stabilizing.

It's never that we block – and then we are done – or that we exapt and then we are done. The cycle (in all its complexities – which we will explore next week) needs to keep repeating to explore the necessary breadth of emergent novelty.

With this sense of the unique cyclical nature of this creative process – let’s return to our story: We left it with dinosaurs developing an expansive array of pigmented feathers which inherently had many potential affordances beyond the stabilizing logic of sexual selection: longer feathers afforded (in the right contexts) effective defensive postures (big displays to scare off would-be predators), defensive distraction (a predator bites off a mouthful of feathers and nothing else) – and a well feathered arm will keep far more eggs warm than a scrawny bald one…

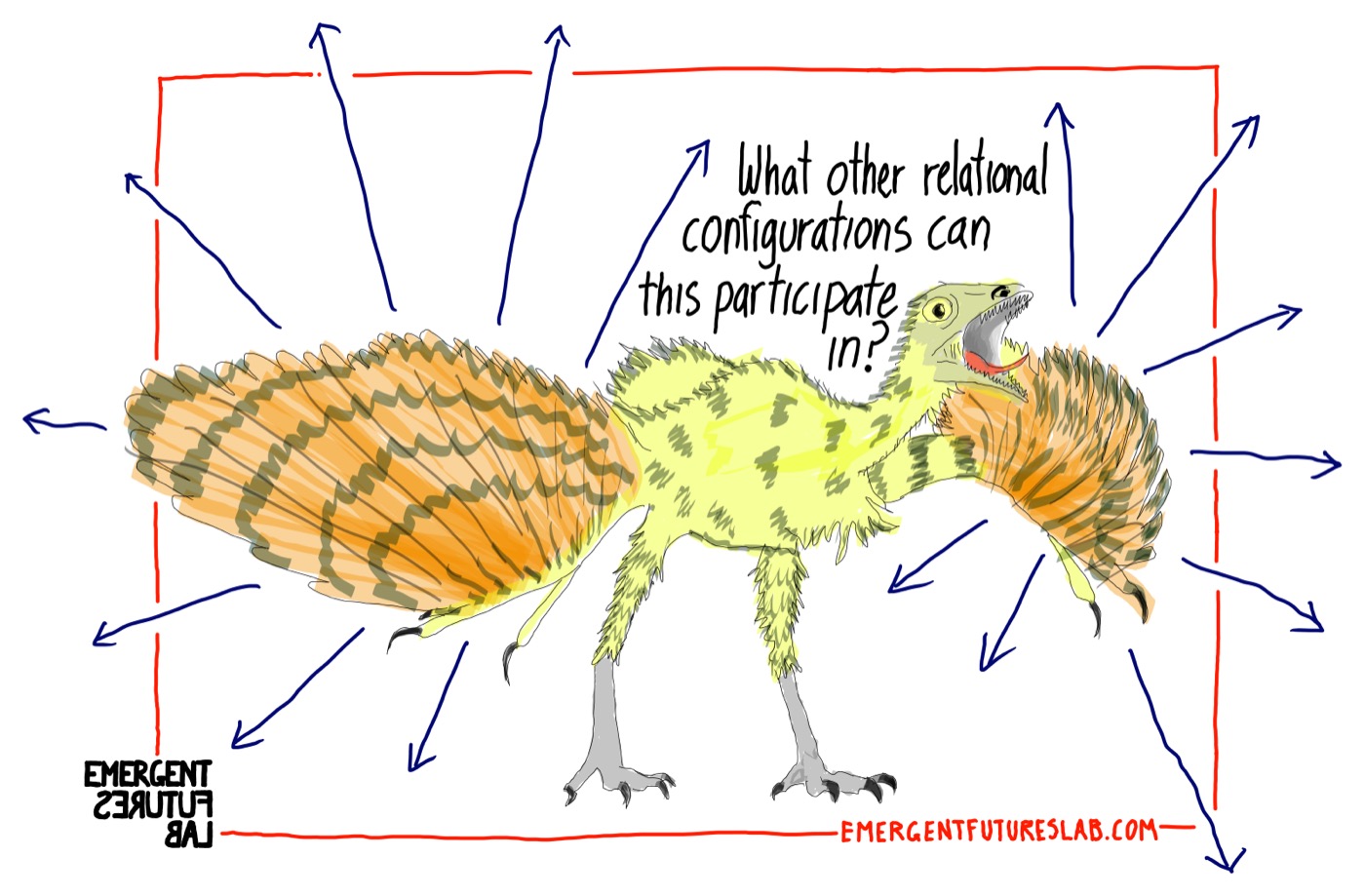

And if we happened upon such a creature with our contemporary sensibilities, we would instinctively call that scary egg-warming arm – a “wing”:

And it is a “wing” – but not a wing for flying.

Remember, as well, this “wing” is not a single thing but a vast field of highly diverse variations settling into diverse patterns of use and “purpose” (something that can only be determined ex post facto).

The relational configurations are themselves ever evolving…

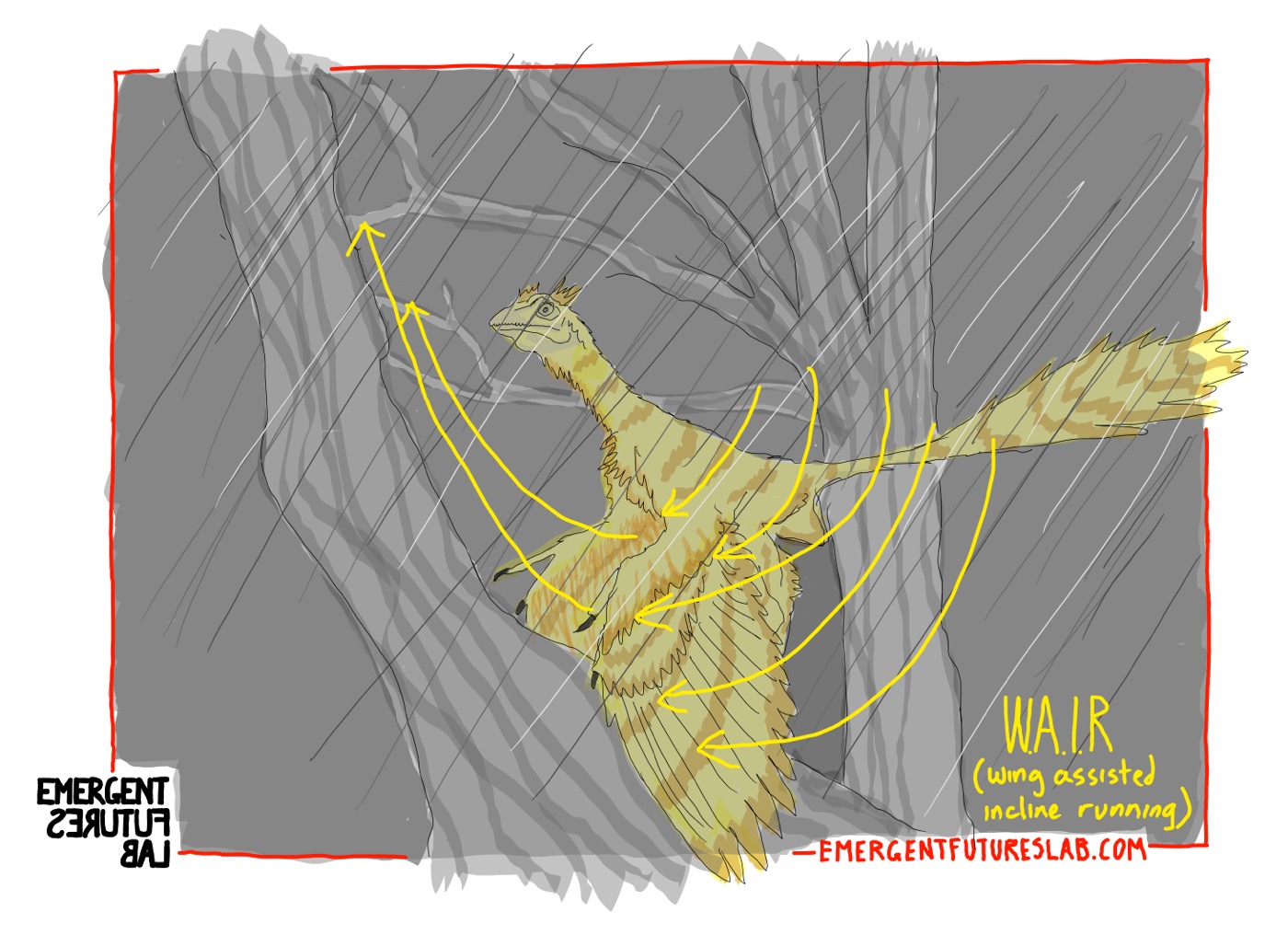

One of the “unintended” affordances of such a wing in the context of emerging forests inhabited by canopy-dwelling small mammals is “wing-assisted incline running” or WAIR for short, emerges. This is where the flapping of the wings inward (not downward) assists in pushing the dinosaur's hind legs into the trunk of the tree, such that it can run up it.

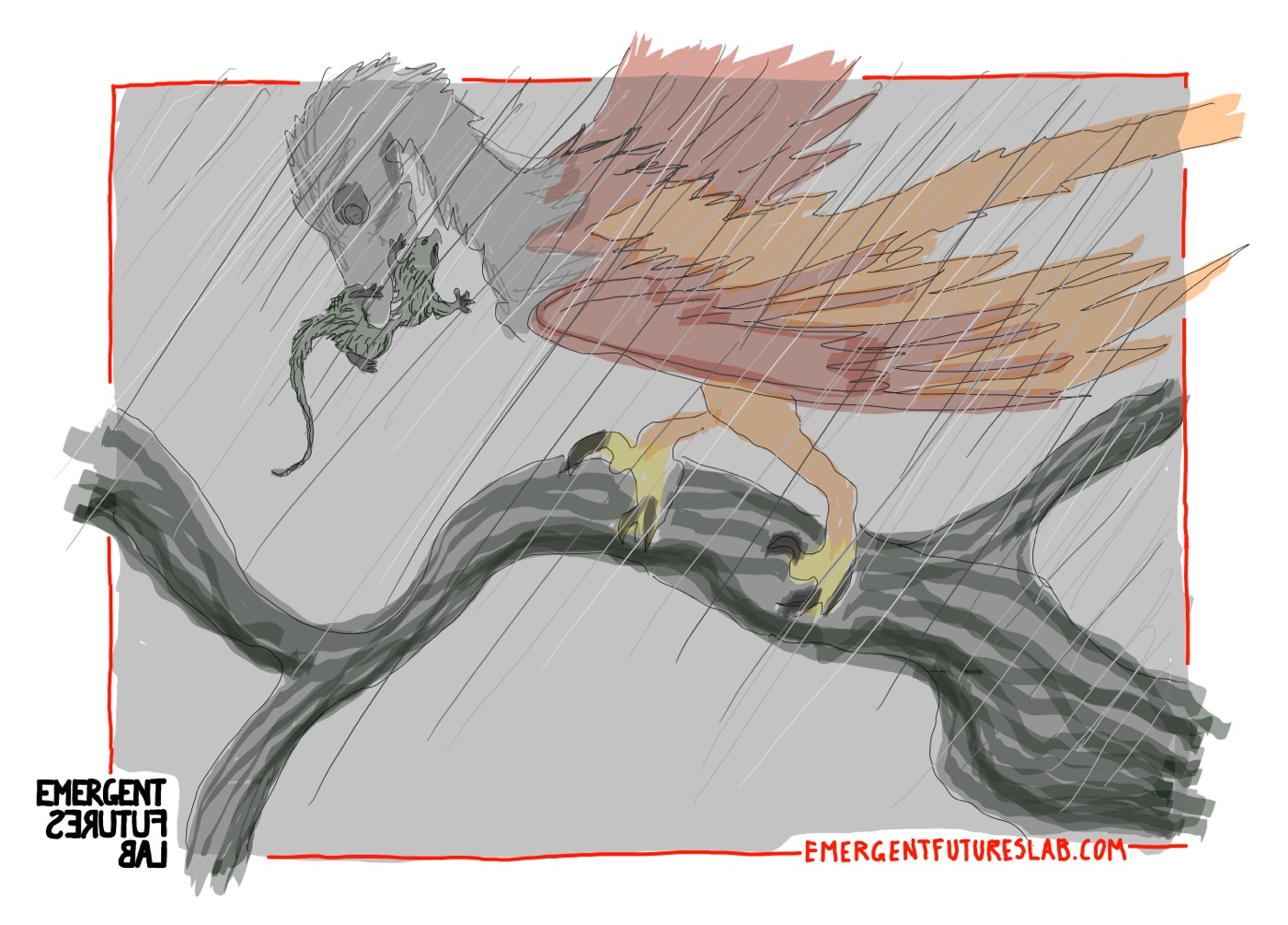

With success comes the novel configurational context that emerges as a problem: how to get down…

For some, this is not an issue – arms and feathers afford down climbing in a wide variety of manners – climbing, hopping, leaping, slipping…

And for many, as with all things, none of these techniques work every time. Falling and tumbling happen.

Having longer arm and leg feathers affords all sorts of falls that don't quite end in serious injury or death. Quasi-parachuting, pseudo-gliding, and semi-controlled tumbling are all afforded. In hindsight (ex post facto), we can see where this story went…

And from this our contemporary vantage point, if we are so predisposed via cultural habits and storytelling tropes, we can read backwards an inevitability, linearity, and singularity into a process that has none of this.

This creative process is not one and done. It is not a process where one unique exaptation happens and then a long process of adaptation takes place. In fact, it is problematic from an evolutionary perspective to talk with certainty of what an “adaptation” might be – as Gary Tomlinson argues,

“The deepest, hardest to eradicate flaw in adaptationist thinking may not be its imagined, temporal causal chain where there is none, but instead its abiding belief in the dis-crete, readily identified trait-for-a-purpose”.

This creative process is not fundamentally an iterative process. Yes, things loop – but these are very different loopings.

The good news is that these are cycles that we can semi-formalize. And this is what we are attempting to explore with our experimental elucidation of “Blocking” Processes:

The Blocking Process (the simple version):

And as we come to the end of this week's newsletter, we have a last question – how does this cyclical process allow for the emergence of the qualitatively new? This is what we are intimating towards in step seven: “And then repeat the process using this new design, starting from step 2 – until a novel qualitative threshold emerges and can be crossed.”

This emergent qualitative threshold is something that is co-created in the process – it is not pre-existent. And that is what we will be exploring next week.

Till then, try experimenting with this full, but still quite simple, process of blocking outlined above. But remember it is not a one-and-done process – and it is never enough to say that it is not a one-and-done process – we have to enact these cycles and their repetitions towards the co-emergence of the qualitatively new.

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.