WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 217! Does Creativity Whisper: Engagements R Us?...

Good Morning activators of what has already situationally transformed you,

It was – is – the week of the super full moon. And it is now the last month of the Atlantic Hurricane season. Storms are still coming strong. The World Central Kitchen is doing great work here in the US, in Jamaica, the Philippines, Gaza, and elsewhere in this regard – there are many ways, if you feel compelled, to participate.

This week, with great sadness, we report the passing of our dear friend and artist, Alison Knowles (1933-2025).

Her work, her presence, and her friendship have had a big impact on how we approach things.

Alison was deeply influential as an artist, musician, philosopher, and publisher – playing a significant role in a number of ethico-aesthetic revolutions from Fluxus to Feminism to Foodways.

She is rightly famous for propositional artworks like, Make a Salad. A work that consisted of those three words.

Making a salad is an everyday act that encompasses worlds, ecologies, systems, and countless beings and ongoing processes in its mode of gathering. It is an activity that most of us are engaged with in any number of ongoing ways.

There are countless approaches we could take to engage this proposition. For me (Iain), I most often appreciate it as the activity of making a salad and eating it, usually with others. Alison’s proposition does not change much, or get in the way of making and eating a salad: A salad is prepared – sometimes from the things we have participated in growing, or foraging, other times, what we bought. Tomatoes found in an overgrown lot, Olive Oil from Jenin, Salt from the Ocean at our doorstep. An old cutting board, a repaired knife, a wooden bowl from a garage sale. Peeling, cutting, dressing, mixing, eating.

For a time, we would visit with Alison quite often, bringing over many things to cook and making dinner with her in her narrow kitchen. Cutting vegetables and drinking small glasses of Vodka. Then sitting on the floor in the main room of her loft – most often talking about mundane things: feet, making paper, beans, books, music, cooking, travels, friends… One time, she told us the story of being invited by the Obamas to recite poetry at the White House. I’m not sure what the occasion was – or if she even told us that detail. The piece she performed was “Shoes of your choice.” It is not what one might normally consider a poem. It certainly does not consist of any of the tropes of the PBS idea of poetic voice and wisdom. It is simply a proposition inviting people to talk about “shoes of your choice”. Alison told us of leaning against the table, taking off her big shoes – for she had big feet, propping her shoes in front of everyone, and just speaking about them. But that was it, with the same attention and care, she proceeded to tell us of other memorable stories that came from the various occasions she had invited people to do this. And soon she had us all talking about shoes that have been our dear companions with the laughter that so often accompanies everyday stories. We never got back to talking about the White House.

At some point later that evening, we are trying on paper shoes she made with cotton and beans. They are thick, flat rectangles of felt-like paper that have been formed into shoes. We took turns moving very gently, sliding lightly on her wooden floors. Testing, experimenting, feeling our way towards.

Much later, we rode the small elevator down – still talking, my partner said, “You know, I think we spent the whole evening engaging with and thoughtfully talking about things – it was never focused on any of us – it was about our co-creative companions – from skin cream to the rain to shoes…”

This morning, as the sun came up and the previous night’s strong winds began to die down, I did a quick search for mentions of shoes in all of our newsletters; they come up in over forty newsletters—our dear friends— human and non, co-creating us. I can't help but think that Alison would be smiling at this. Alison – you are missed.

This week, we continue our series on the tasks of Engage in how we deliberately interact with ongoing creative processes and their emergent fields of possible actions.

The first question is: why stres engagement? How is engagement as a practice important – or even relevant to creative practices?

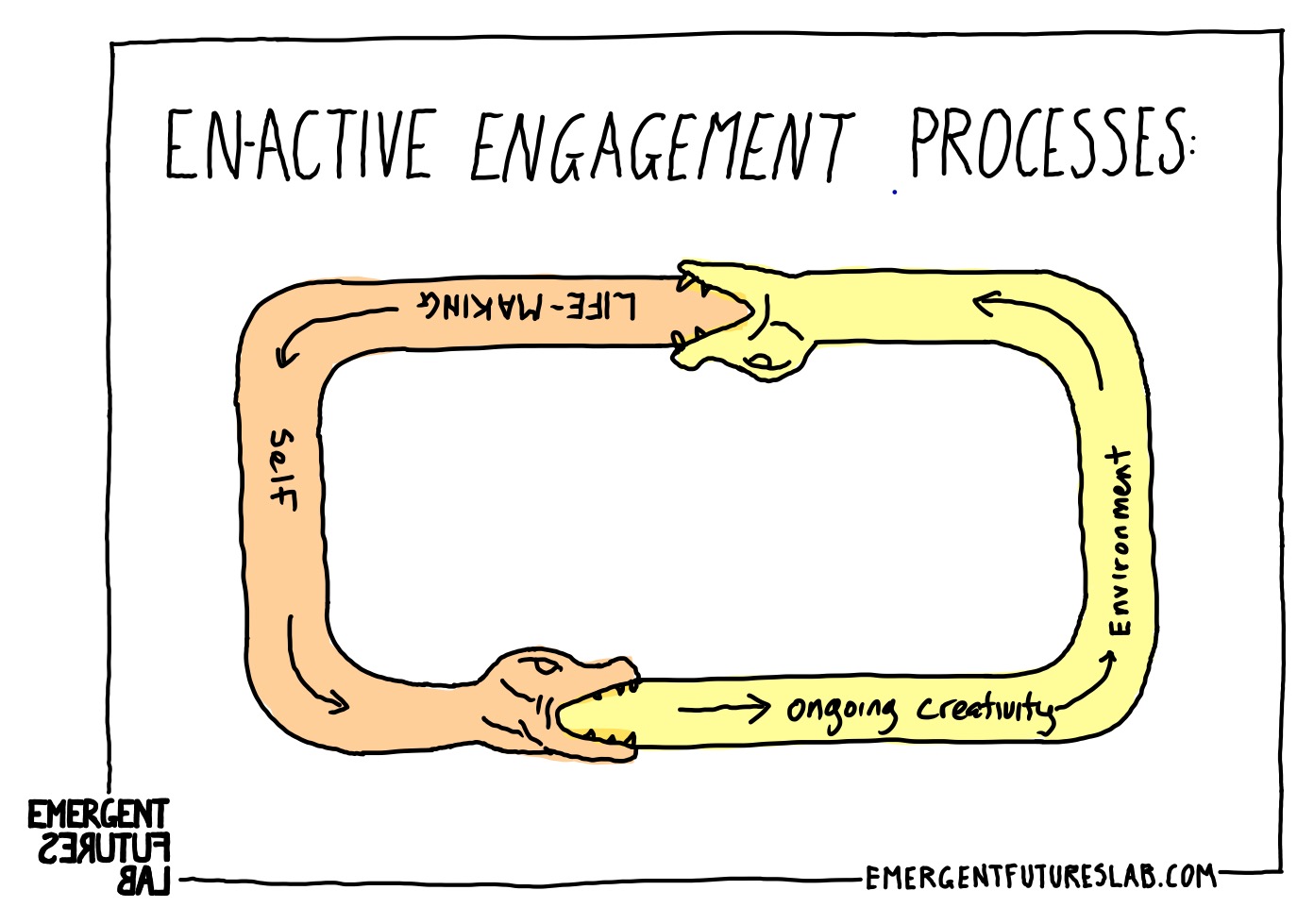

Last week, we addressed this question from the perspective of direct experience and how the world’s ongoing creativeness exceeds our knowledge. Because of these two factors (that reality is (1) inherently creative, and (2) its potentialities exceed knowing and knowability whatsoever), we are always engaged in an ongoing world that both exceeds our knowing – and is in turn transformatively shaping us.

The necessity of engagement is because creative potentialities are relational – they are not hidden deep in some mystical inner essence of things but in their infinite and open relational possibilities. Given that no relations are fixed and must instead be made and maintained, we have, so to speak, no option other than to be actively engaged in a creative reality that is actively engaged in us.

That is where we left things last week. This week, we want to explore engagement in a way that extends this perspective further into how we can and perhaps should prepare to engage with creative experiments.

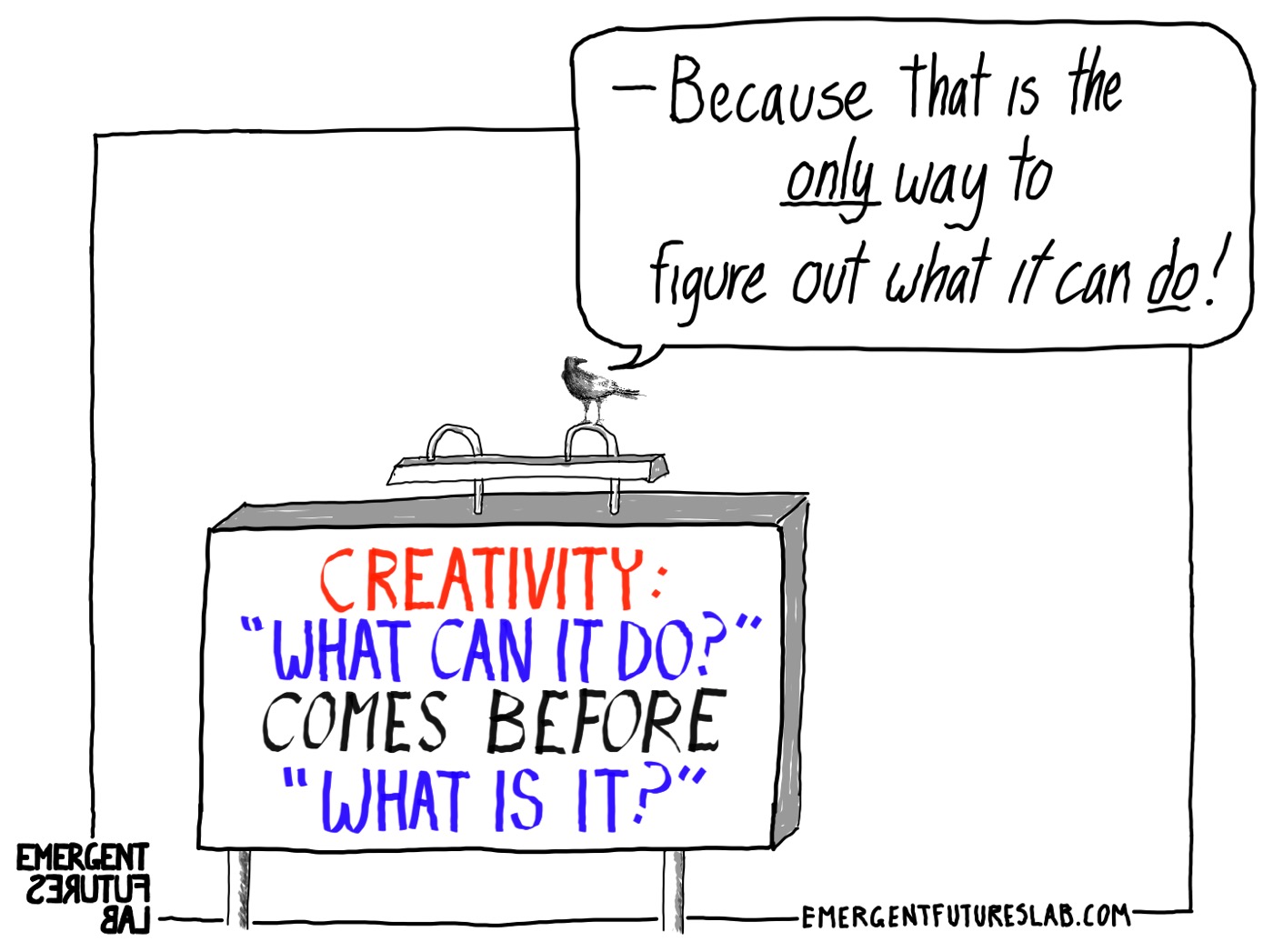

So, why engage? From a creative perspective, the answer is clear: because this is the only way to figure out what things can do that goes beyond the known. We simply cannot know what things are capable of any other way:

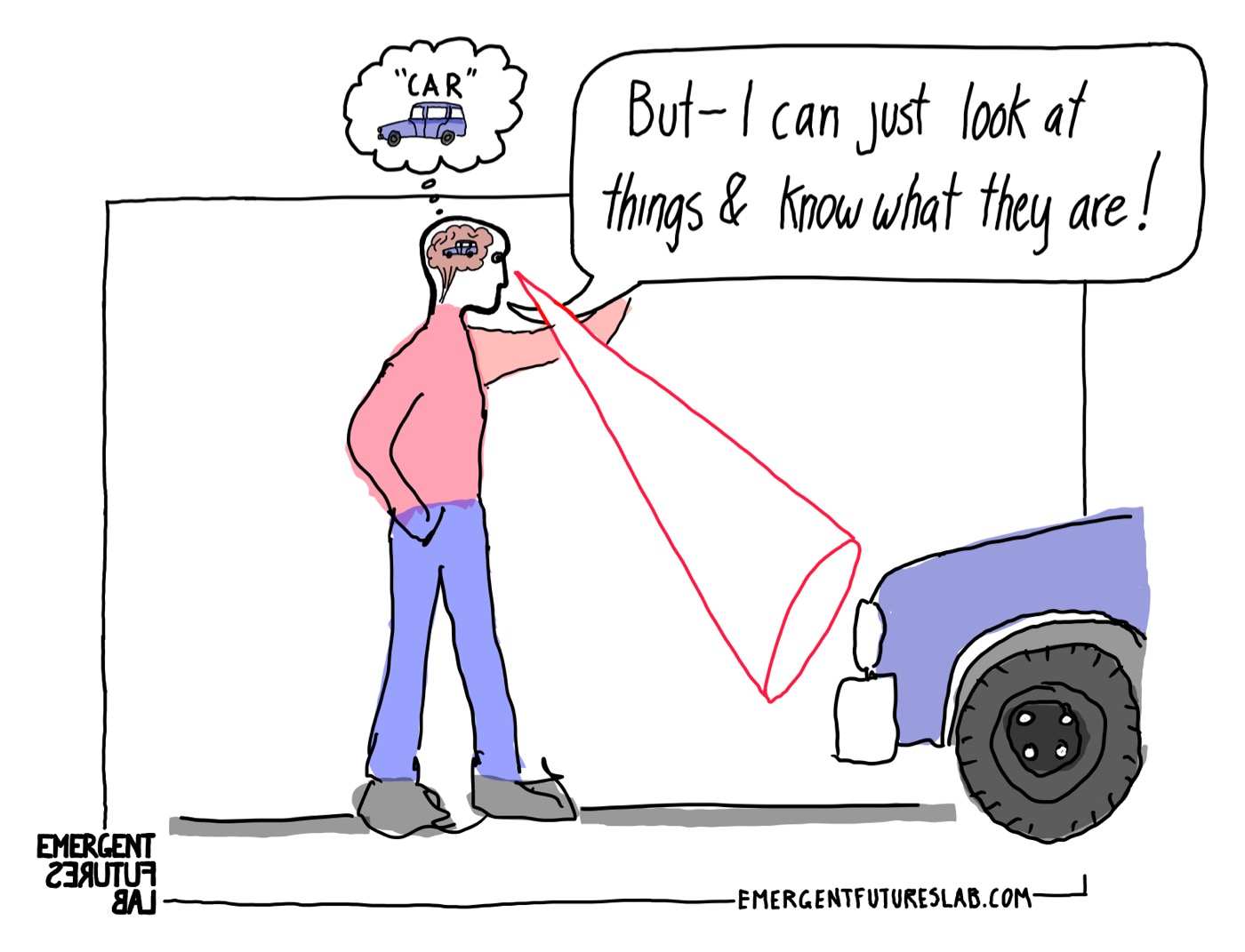

The common rebuttal to this claim that we often confront is,

“But, why?” and here the questioner will wave their hand in a dramatic sweep, broadly pointing to everything around them. “ …I can just look out at all of these things and see exactly what they do!”

Yes, it is true we can look out and identify things as certain things with certain purposes and properties. But this will be based upon our previous engagements, both conceptual and physical: I know what a car is (for me as someone embodied and embedded in this culture in a certain manner). And I can see this car quite clearly:

But does this form of explicit knowing encompass all future ways that this car could be taken up by distinct experimental practices?

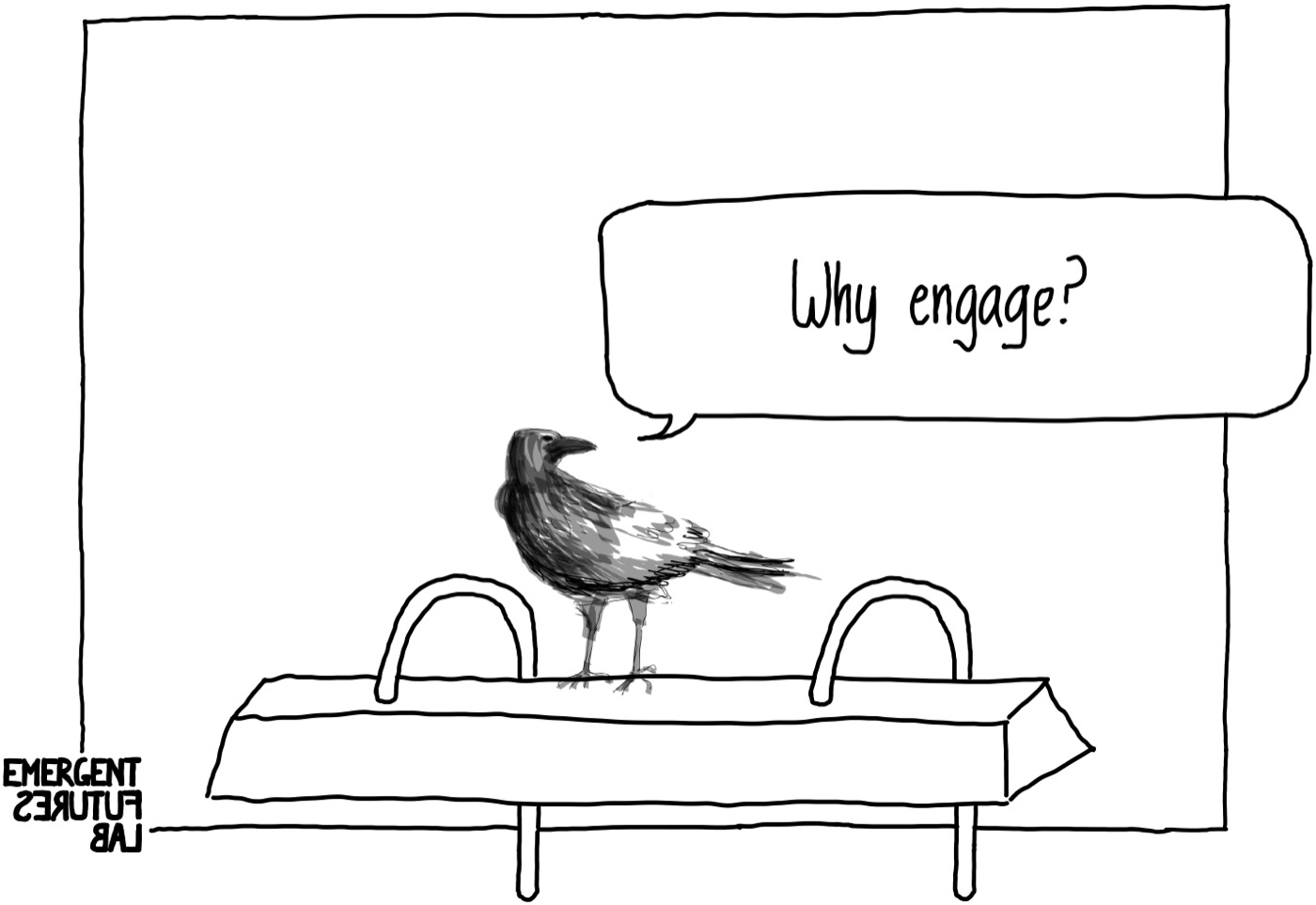

Not at all. To cite one of our favorite examples: some crows have come to invent ways to use cars as a key aspect of their nutcracking engagements:

Crows will place nuts at traffic intersections when the lights turn red and then wait for the light to turn green and the cars to crack the nuts. Then, with the lights again turned red, they will fly down and collect their cracked nuts.

What anything can do – a car cracking nuts, for example, is a contingent, relational, and emergent property of an engagement. The ever-emerging meaning of a car is ultimately nowhere to be found in the intentions, identity, or purpose of any part of this system. The road was never intended to crack nuts or host crow behaviors, neither was the car, and neither was the traffic intersection. But, this is what is happening.

Ultimately, this (unintended) use of the car is not some exotic, highly unusual event – but the most common of occurrences. We are doing this (the experimental co-opting of things for unintended uses) all the time – as are every living being. Cars are used for housing, chicken coops, business deals, meetings, as market stalls, political ads, outdoor lighting systems…

Because of this, it should come as no surprise that crows also have “cars” in their worlds. But, they are not our “cars,” after all, they afford – provide the opportunity for – very different actions in their world than the “car” does in our world. So while the car and much else are part of the same shared space, the crow lives in very different affordance-based worlds from us because of our distinct forms of embodied engagements..

Now we can come back to our point about sight and perception: None of this can be “seen” by simply looking at a car! You can look as hard as you want at a car in the dealer's showroom, on the street, and elsewhere – but until such a novel activity emerges that co-creates these novel affordances of nut cracking, it is, as with anything that does not exist, categorically unknowable. Of course, after the fact, it can be easily known with the right experts, questions, and research methods. But even after compiling the most authoritative list of all of the qualitatively distinct uses of a car, we cannot say that “we know all of what a car can do.”

The new will always emerge in and of an engagement that exceeds the known (and the visible).

The astonishing fact of the matter is that we can never pre-identify what will come to matter in novel engagements with things. The underlying emergent and contingent functional contribution that the thing provides in some novel engagement will always vary uniquely (based on which novel and unexpected aspect is co-opted by the configuration) – see Volume 214.

And this gets at something fundamental about seeing, perception, and engagement: Seeing is an enactive practice (a situated engagement). We see a car as a “car” and not a nutcracker, because of what we do with it, and how it fits in our world. Our perceptions are not a “view from nowhere” – nor can there ever be such a view – our perceptions, like all perception, are the emergent outcomes of our situated engagements.

Because we, as embodied beings, open car doors, sit down behind the wheel, turn keys, and pull out into traffic. Because we walk on sidewalks beside whizzing traffic, watch movies about the open road, and are confronted by billboards of cars as we get exhausted waiting for buses in the rain that never come. Because we feel them brushing past us dangerously while commuting on our bikes, they become “cars” and we perceive them as such.

Active relational, interactive, and embodied meaningfully situated engagement is what gives rise to sensing, sense-making, perception, feeling, and knowing. This form of grounded, relational, experiential engagement is foundational.

These insights of the importance of engagement are not simply for the birds, movie critics waxing poetic about the open road, the pathos of the seduction of cars, or even the car’s embarrassed loss to fully grasp what a road can do as Gene Kelly skates by... They apply equally in organizational contexts.

In organizational situations, the meaning and possibilities of any thing are also the relational outcome of engagements. Both what we decide in a situation and who we are in a situation are ultimately the outcome of complex relational engagements.

Many organizational consultants still perplexingly stress, test, measure, and inculcate an individualistic trait-based approach to job aptitude, leadership, and creativity. Which is to say, they claim that the best way to understand what we will do and who we are in a situation is via the understanding of our internal and underlying personality traits (such as the so-called big five of Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism etc.).

But, we can already see that what is possible in a situation (what it “affords”) – as well as what we perceive and understand of a situation is the emergent outcome of an engaged relational practice. How we act is far more the outcome of the engagement with the situational context.

A very simple, profound, and astonishing example: the embodied embedded engagement with the specifics of a chair – specifically its hardness or softness – participates in the shaping of our perception and our judgment of criminal activity:

“Our results… show that priming the participants with an active experience of a hard object made them harder on crime relative to soft priming or no priming at all. This is demonstrated by behavioral results, showing that the experience of hard objects (sitting in a hard chair) made participants harder on crime, but did not make the participants generally feel more negatively. Hence, “hardness” had an effect on judgments of criminal severity, thus documenting an extralegal factor in judgment processes”.

And the authors of this study, published in the journal Nature (April 2018), conclude:

“Based on the results of Ackerman et al. and the present study, we suggest that incidental haptic experiences such as hardness of objects or even furniture (chairs) may influence judgments rendered in actual courtrooms… [T]here seem to be numerous real-world examples documenting that even very experienced judges are not completely immune to extralegal factors (e.g., the field studies in California courtrooms by Konecni and Ebbesen), which suggests that even highly trained individuals may be susceptible to such effects.”

So… when we ask, what could feel like such a trivial and obvious question: what does a chair do?

The answer is anything but trivial or obvious…

Our situated embodied enactive engagements are anything but trivial.

Our question this week is: how should we prepare to engage with creative experiments?

And in the light of the above discussion, the answer has to involve the slowing down and experimenting with the configurations that we are engaged with such as that we can come to sense specifically how they play a profound role in co-creating us via our embodied and embedded engagements such that what and how we feel, see, sense and do is afforded by this co-creative entangled engagement.

On Thursday, all of this came up during the discussion in the weekly meeting of our community of practice, WorldMakers. And we were reminded of what we wrote in Volume 210:

“The problem of creativity is never one of how to make something from nothing, but how to work one's way out of sedimented systems long enough to experimentally invent and co-emerge with new, different processes.”

The question of how we do this is never a personal one, nor is it graspable via trait psychology. It is an organizational one. It is about environments, infrastructures, procedures, tools, habits, HR… In short, it is about how these engaged relational situations have always already co-created the spaces of possibility, as well as our sensing and sense-making capacities.

As we come to the end of this week's newsletter:

How can you develop ways to engage with things such that you sense their co-creative agency in your being – and how can you shift your engagements towards the co-creation of more experimental ways of sensing and sense-making such that new propensities might pull one elsewhere?

We are curious about your own experiments in this regard, as next week we will dig further into this in regard to organizations and creative practices. Please feel free to share your thoughts; we are genuinely interested.

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.