WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 218! Creative Engagement: Stepping Into the River That We Are Already In...

Good Morning historically situated activated environments,

First, thank you for the kind emails in remembrance of Alison Knowles. A few of you asked for more details about her life: here is one of the many obituaries.

Our question this week is the same as last week:

How should we prepare to engage with creative experiments?

It's a question that asks us to investigate what comes before we begin a deliberate creative experiment. This is something we in Emergent Futures Lab think about and experiment with quite a bit.

For us, in our work, it is always a welcome occurrence when the topic of the newsletter and the topics of our consulting work align. This is one of those weeks. Over the last few days, we have been busily preparing for two keynotes and a workshop that we will be giving over the next couple of weeks on the topic of: How should we prepare to engage with creative experiments?

Even more fortunate for us, this task of how to prepare for creative experiments, which we term Engage, has also been the focus of the discussions and workshops in our community of creative practice, WorldMakers, for the last couple of weeks.

The challenge of beginnings when we wish to do something different is the challenge of being alive. At every moment, we are always already fully entangled in-and-of the stream of a situated way of being alive that has a strong directedness to it. In some sense, when we try to do something different, we find that we are in large oceanic currents trying to both go with them and go in new ways.

We are always in the stream, but we wish to enter it anew, such that it could carry us forward differently.

The place to start is with our immediate experience in the context of what our interest is. But experience is profoundly paradoxical. It is neither subjective – just something totally personal, nor is it objective – just about bare physical facts. So what is this? First, it is very real.

We have often used the example of water and swimming pools to get at this paradoxical quality of experience: To a person jumping into a swimming pool on a summer day, they are met by a liquid that surrounds their body, slowing them and ultimately suspending them in the water buoyantly.

But to a small water skimming insect – a Water Strider, it is not experiencing water as a liquid that they float or sink in whatsoever, but rather as a tensile surface.

To a paramecium, the water is thick, syrupy.

And to a single-cell bacterium, this same “water” is experienced as something that they are bounced around in by molecules.

In all these cases, it is the same physical thing, “water” – but the very real and consequential experiences are wholly qualitatively different.

What shows up for us as what we experience and what shows up for us as relevant – is very real – but it is not to be found either purely in us (something we would understand as subjective), nor is it purely “out there” in an objective neutral reality (something we would understand as objective). Our experiential and very consequential reality is something that is brought forth into being via skilled, embodied, and embedded action. The Enactivist researchers Veraeke and Mastropietro have coined the term “transjective” to get at the relational interactive quality of lived experience:

“What is relevant to an organism in its environment is never an entirely subjective or objective feature. Instead, it is transjective, arising through the interaction of the agent with the world. In other words, the organism enacts, and thereby brings forth, its own world of meaning and value.” (Jaeger et al)

Importantly, this experience profoundly shifts relationally as well: if we as embodied humans now decide to dive into that same pool from a very great height, nothing about the physical properties of the water will change, but when our diving body now meets the water, it will not part around our body and gently slow it down. The experience will be one of hitting a very hard, solid object that will crush our bones and organs, no differently than hitting a concrete sidewalk from a great height.

This week, we want to move this transjective experience of water and swimming pools into a different adventure: our organizational lives. What do organizational configurations give us as an immediate, direct experience?

The Japanese philosopher Kitarō Nishida (1870-1945) wrote some of the most insightful work on direct experience, starting with his 1911 work, An Inquiry into the Good, written while he was a young high school teacher. Twenty-five years later, reflecting on this groundbreaking early work on direct experience, he wrote:

"That which I called...the world of direct or pure experience… I have now come to think of as the world of historical reality. The world of enactive intuition – the world of poeisis (making) – is none other than the world of pure experience."

We should sense that our direct experience of jumping into a body of water is this world of “historical reality” – as is any other experience.

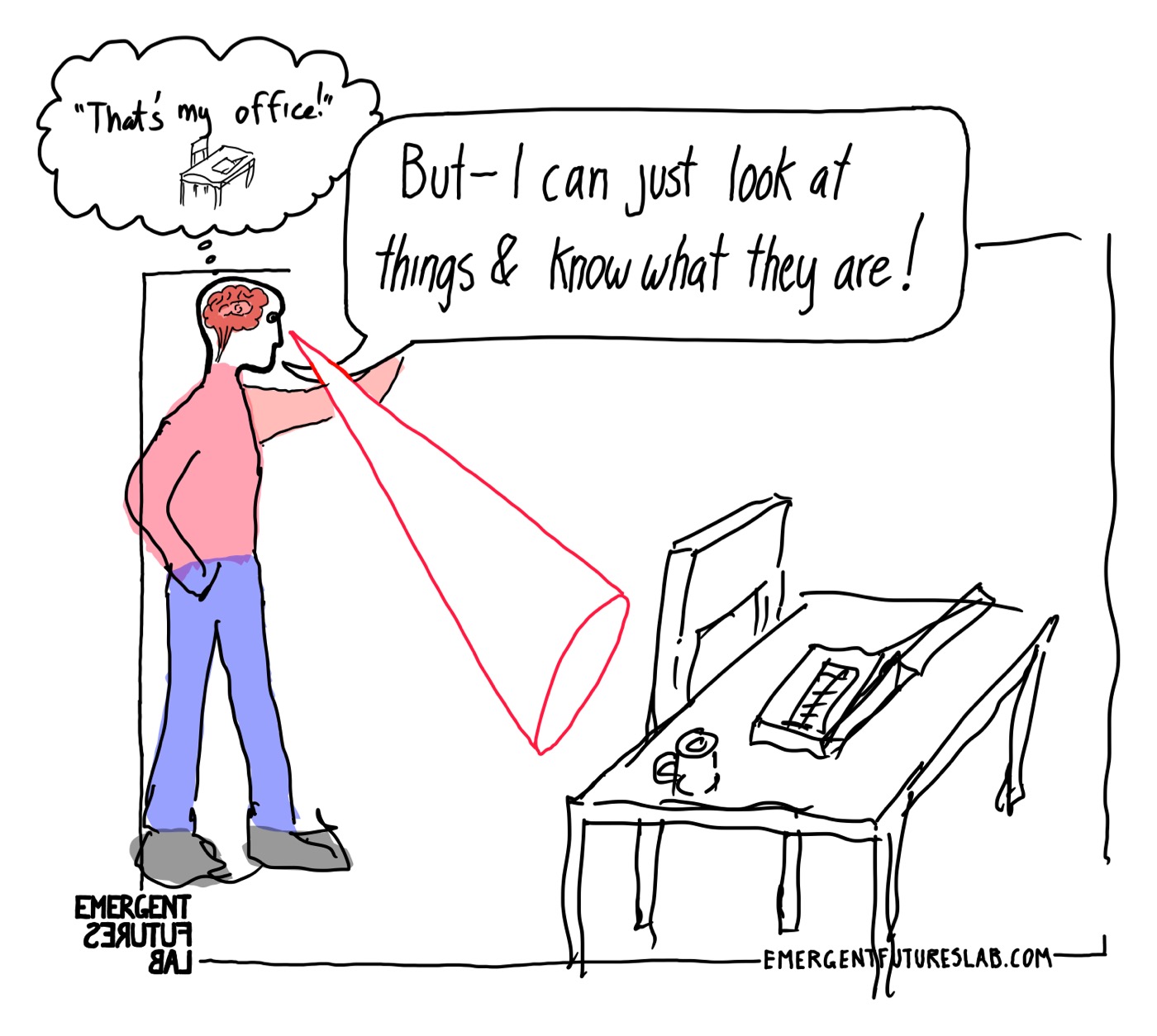

When we have the experience of the kind we discussed last week, where we can just look at things and know what they are, what are we seeing?

Experiences. This is all we have. Direct experience: We have the experience of seeing, moving, doing. And this experience is both immediate, holistic, and total. By this, I mean that experience is not something we need to put together. It is direct – there is no before to experience.

When we, for example, open our eyes as we awake from a power nap at work, we do not experience strange colors pressing against our eyes that we need to stabilize, organize into discreet spatial units, and finally interpret into meaning. No. Rather, upon waking, we, as fully embodied beings, experience our world as a world. We don’t see indeterminate colors – we “have” a room with clear, recognizable things. We don’t lie frozen, head on arms, puzzled by things, tentatively reaching out with our hands to make sure our body, the desk, and the floor are “real.”

Experience comes to us pre-conceptualized. We open our eyes knowing “office” “wall” “floor” “table” “tablet” etc. Of course, we might get things wrong – what I see, for example, across the room as a small sculpture of a dog could turn out on closer inspection to be something else. This is a common experience – and one that makes clear how experience works: we always see things as things.

But this way of phrasing it misses something critical: what do we really mean by “things”?

If we go back for a moment to our water example: standing beside the pool, we see “water” – it is a “thing”. But the total embodied and active experience that seeing is a part of – is one of feeling-sensing-knowing water far more intimately as a space of holistic opportunities. Because I, for example, have learnt to swim and be around pools and water, it holistically affords me an active experience that pulls me forward into pathways of action: jumping, diving, splashing, floating, rolling, swimming… Experience is always an active experience of what Nishida called action-intuitions.

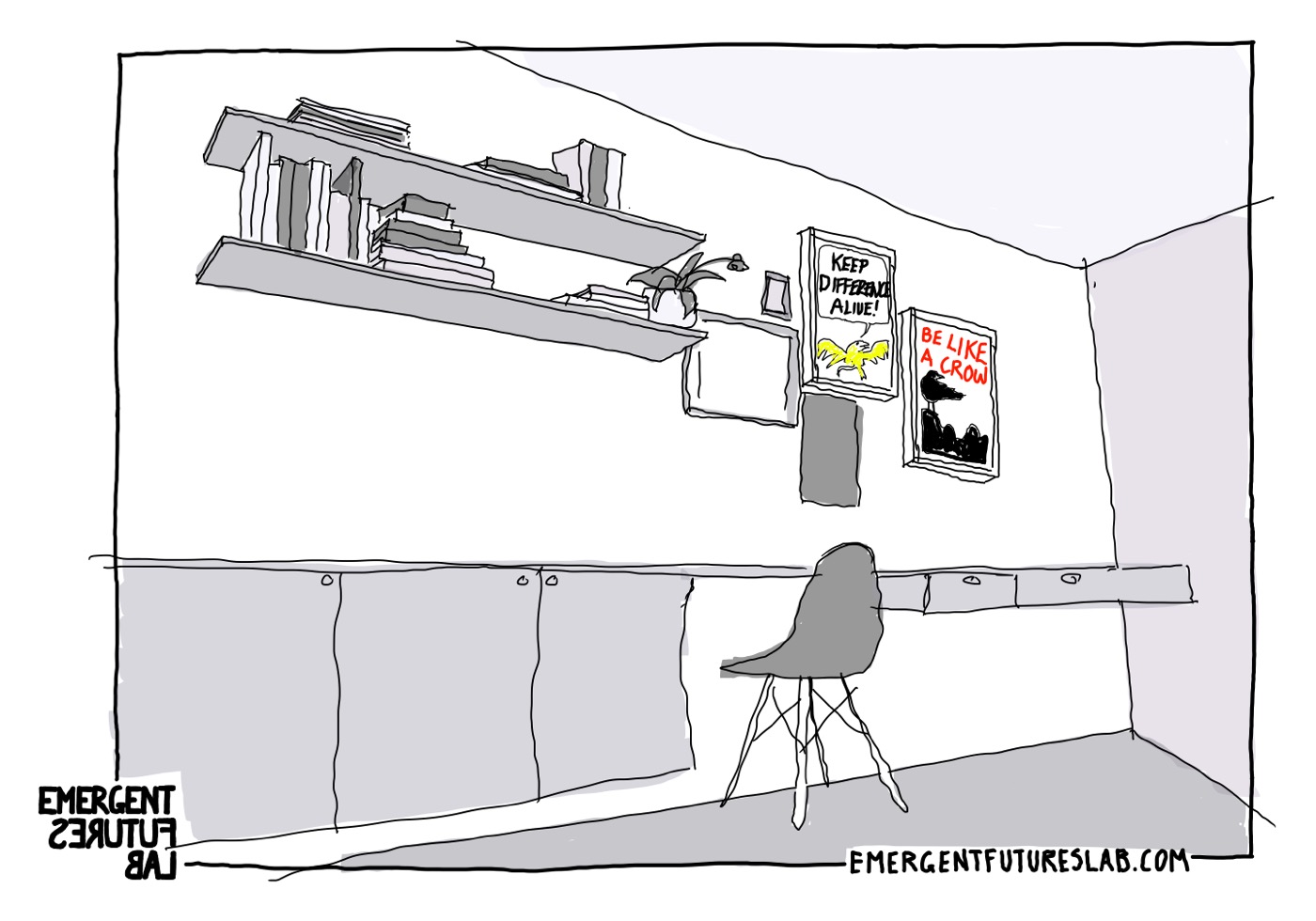

I don’t simply see water as “water” – as a “thing” – I know it directly at an embodied and non-reflective level as a specific living “world” of action and doing. And this is equally true in what might feel like a far more mundane and passive setting, like an office space. We non-consciously sense this world as well as a lived world of shaped action possibilities.

This is what Nishida means by needing to understand “pure experience” as “the world of historical reality.” He goes on to speak of this direct experience as the immediate feeling of “action-intuition” – we don’t stand frozen in space staring at the water or our office piecing together all the discreet parts of the environment and then making the determination, “oh! this is my office” – and then asking ourselves, “I wonder where I should put my foot next – can I step on this stuff in front of me?”

Just as when we are swimming in the pool, we directly feel the pull – the action intuition of the transjective logic of experience – we are actively of this world and move with its pulls, which we see as things. And when asked, we would accurately name these as desks, chairs, books, carpets, etc. But our immediate experience is one of doing.

Experience is an activity – a formative and formed activity. We are collaboratively en-acting a world that is already underway.

And this is the challenge we will always face when we try to do something different. We are always faced with the stubborn fact that experience is pre-formed as directly felt action patterns and explicitly known in a specific conceptual manner – our pure experience is always an active co-creating historical reality.

Why this is a problem from the perspective of engaging with creative processes is that we know that explicit forms of thinking – with its reliance on representational logics of concepts and images is fundamentally conservative, but the strategy of turning to direct experience as an alternative “more creative” and perhaps even more “intuitive” starting place will not give us the hoped for direct and unmediated access to novel possibilities. It is also profoundly shaped and shaping in a direct and unmediated way.

The long and short of things is that when we decide to begin to engage with creative processes, we do not start at a neutral place.

Direct experience is not a neutral place.

Just jumping in and hoping for the best with sticky notes, empathy, curiosity, great, well-caffeinated, willing participants known for their creative spark in a space convivial to openness and engagement – is never going to get us anywhere new.

The challenge is that we, as individuals, are not who we are because we are independent of our bodies, habits, practices, others, environments, tools, and concepts – but precisely because of them.

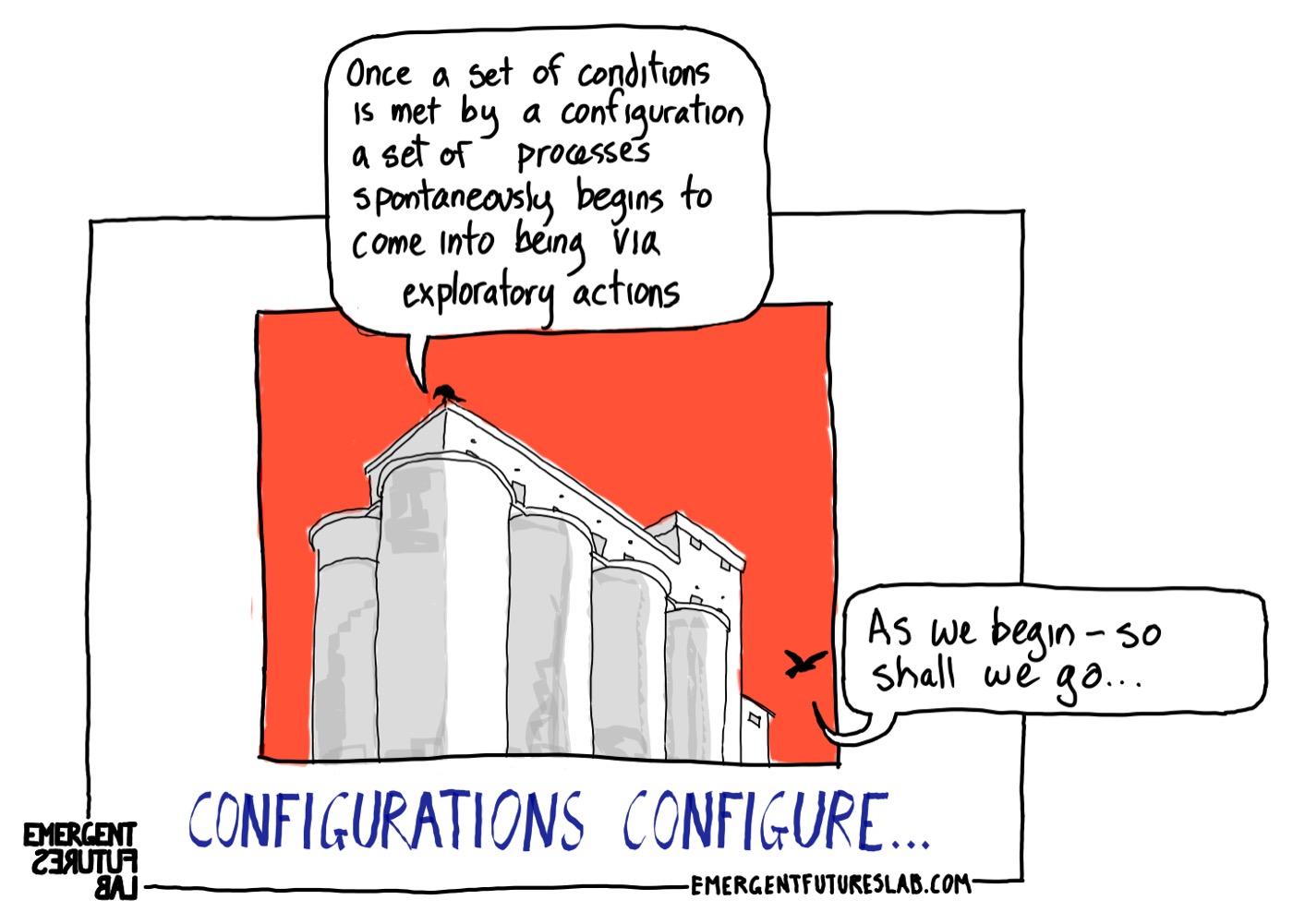

These environments, conjoined with our practices in them, are already pre-formed worlds of patterned action-intuitions, which is to say, we already pre-consciously know what to do with what this world affords us as general opportunities for action.

Again: we “see” things as things: a room with tables, chairs, easels, markers, sticky notes, coffee, and snacks – and in seeing it “out there” we feel that we are radically distinct from it. But this is not the case – we directly “know” it and are of it, in a wholly embodied manner – this world and its propensities are experienced as the direct experience of a certain set of behaviors.

And we urgently need to ask, just like we could ask of our entanglements with the pool, what are the directly experienced propensities for action of this entanglement? Being perhaps too polemic for the sake of making a point: Board-Rooms set up with easels, sticky notes, break-out spaces, and the convening of the usual subjects move us into the flow of interchangeable ideation matrices –that can only come to exist as very general proposals for unknown others to carry out in some unspecificed manner. And this is profoundly far from anything either creative or impactful.

These are spaces where the action-intuitions converge of conceptual ideations, and such practices of representational ideation will always be conservative (see: the creativity paradox).

But while this poses a serious problem for the development of a creative practice, this is by no means the end of our issues when we seek to begin entangling with creative processes. These spaces and tools do not simply pre-conceptualize our possible outcomes. In addition to the problems of pre-conceptualization, we are, as the above example of the boardroom illustrates, faced with critical environmental and situational questions.

Let's consider the role of the environment in co-creating our experience: Experience is something we take as neutral, natural, and given – it is just an experience of a reality that is simply “out-there”.

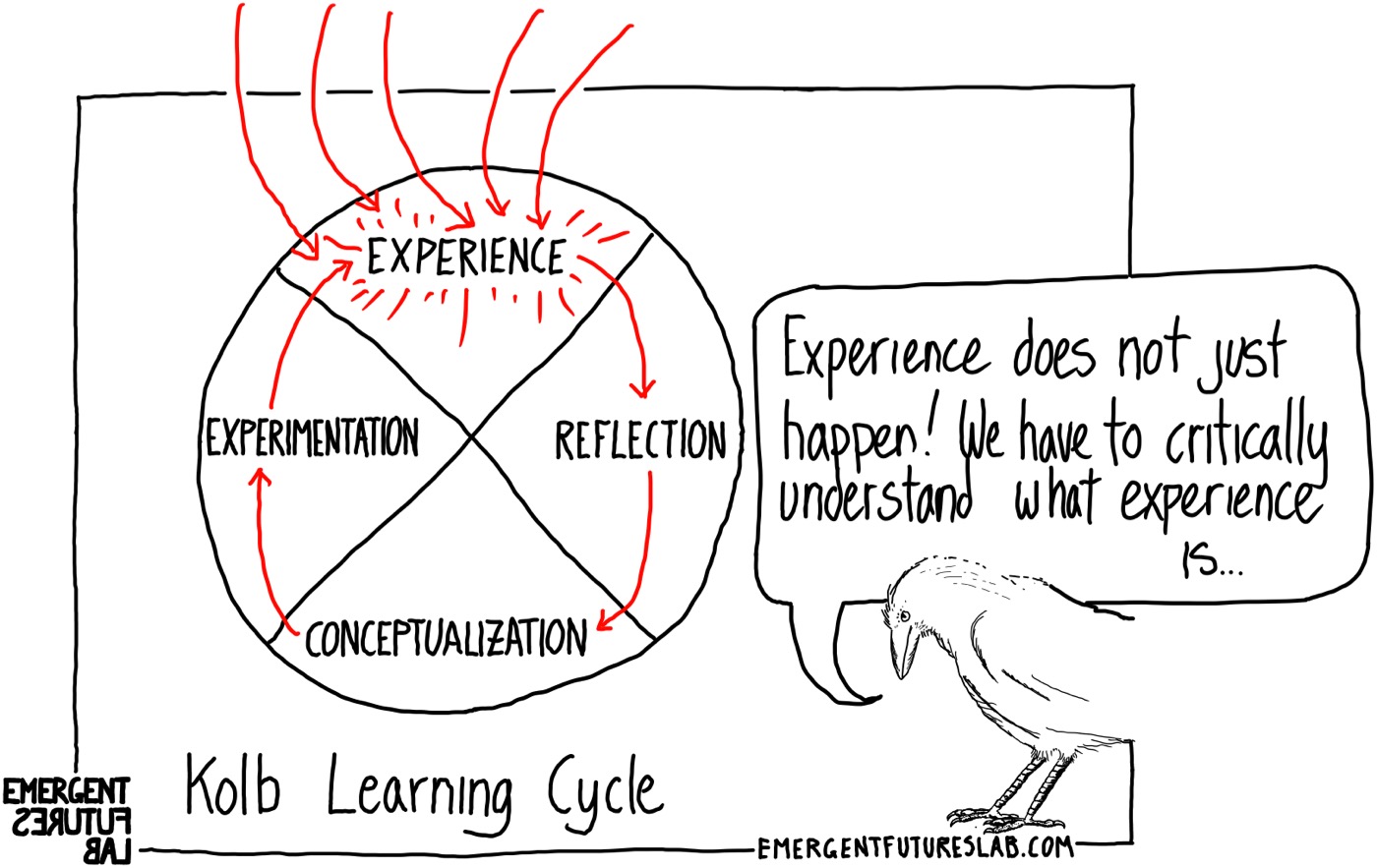

We can see this assumption most clearly in some of the classical experiential learning models, such as Kolb’s Learning Cycle:

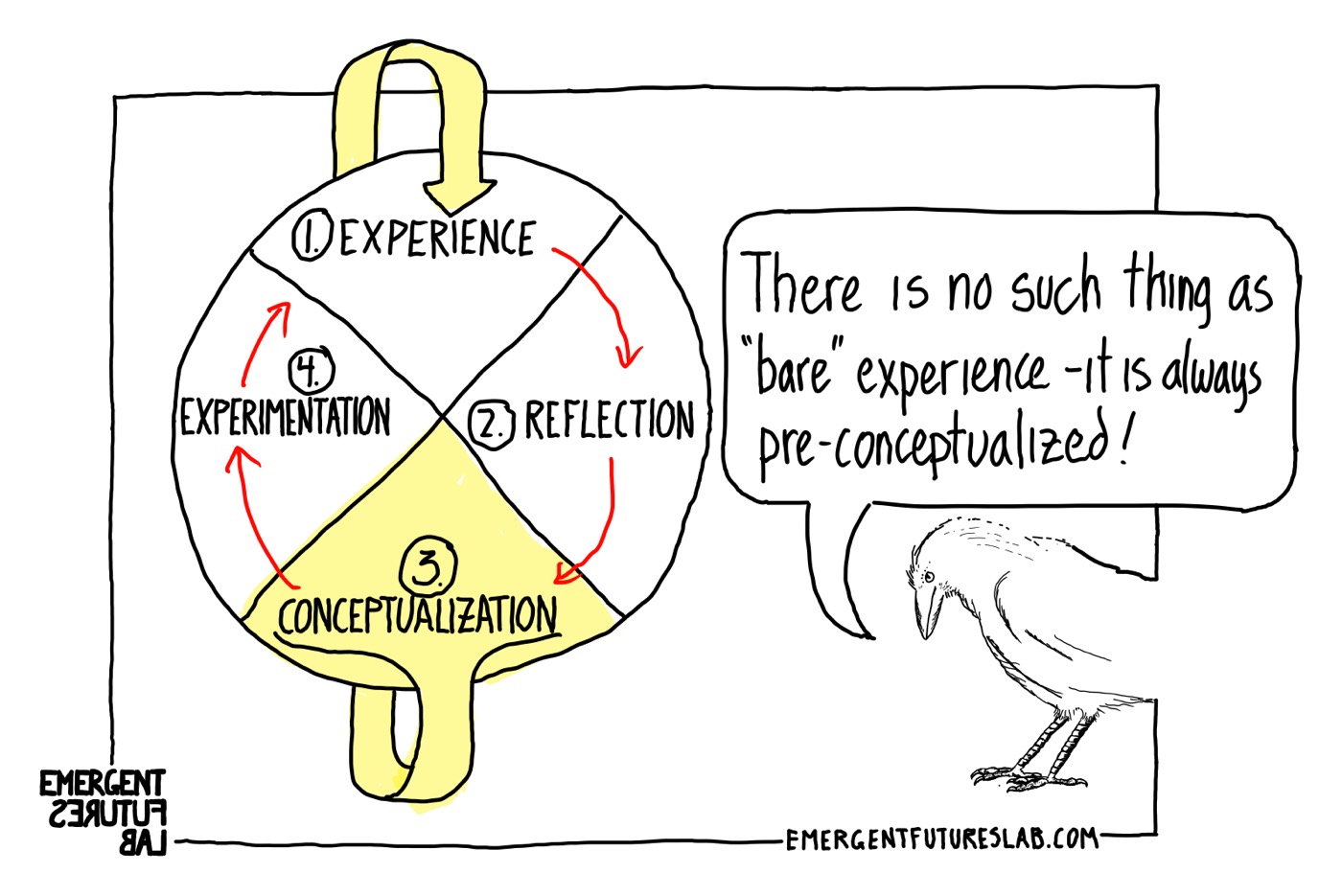

For Kolb and other developers of experiential learning approaches, experience is just something we have, that we can then reflect upon, conceptualize, and then experiment with. But, as we have noted, the first challenge to this model of experience is that what Kolb conceives of as the third stage of engagement is already shaping the first:

Our most direct and immediate of experiences are already pre-conceptualized (we see things as things).

But, to add further complexity to such models of experience, engagement, and learning, our experiences are not simply pre-conceptualized – they are the relational outcomes of how we interact with our immediate environment: they are relational outcomes of how we are historically embodied, embedded, and extended:

This is what our swimming pool teaches us. And it is equally what a chair teaches us: If you remember, in the last newsletter we looked at a seemingly simple example of how, as embodied beings, our environment feels and presses into our bodies in ways that participates in the shaping of our experiences:

For persons situated in the context of passing criminal judgment, the hardness or softness of their chair participates in the shaping of our perception and our judgment of criminal activity:

“Based on the results of Ackerman et al. and the present study, we suggest that incidental haptic experiences such as hardness of objects or even furniture (chairs) may influence judgments rendered in actual courtrooms…”

Now it would be easy to exaggerate the conclusions of this study and jump to hastily claiming that the chair causes a certain judgment. That would be a gross exaggeration and a profound misunderstanding. Falling back on such a logic of linear causality is of no use in these complex circumstances. But there is no denying that our experiences, and our actions, are the emergent outcomes of how we as embodied, embedded, extended, and affective beings that enact “and thereby brings forth its own world of meaning and value” as Jaeger and colleagues write (see above). And that the two E’s of being Embedded and Extended speak to the relational non-linear effects of tools and environments in co-creating how we feel, sense, and act.

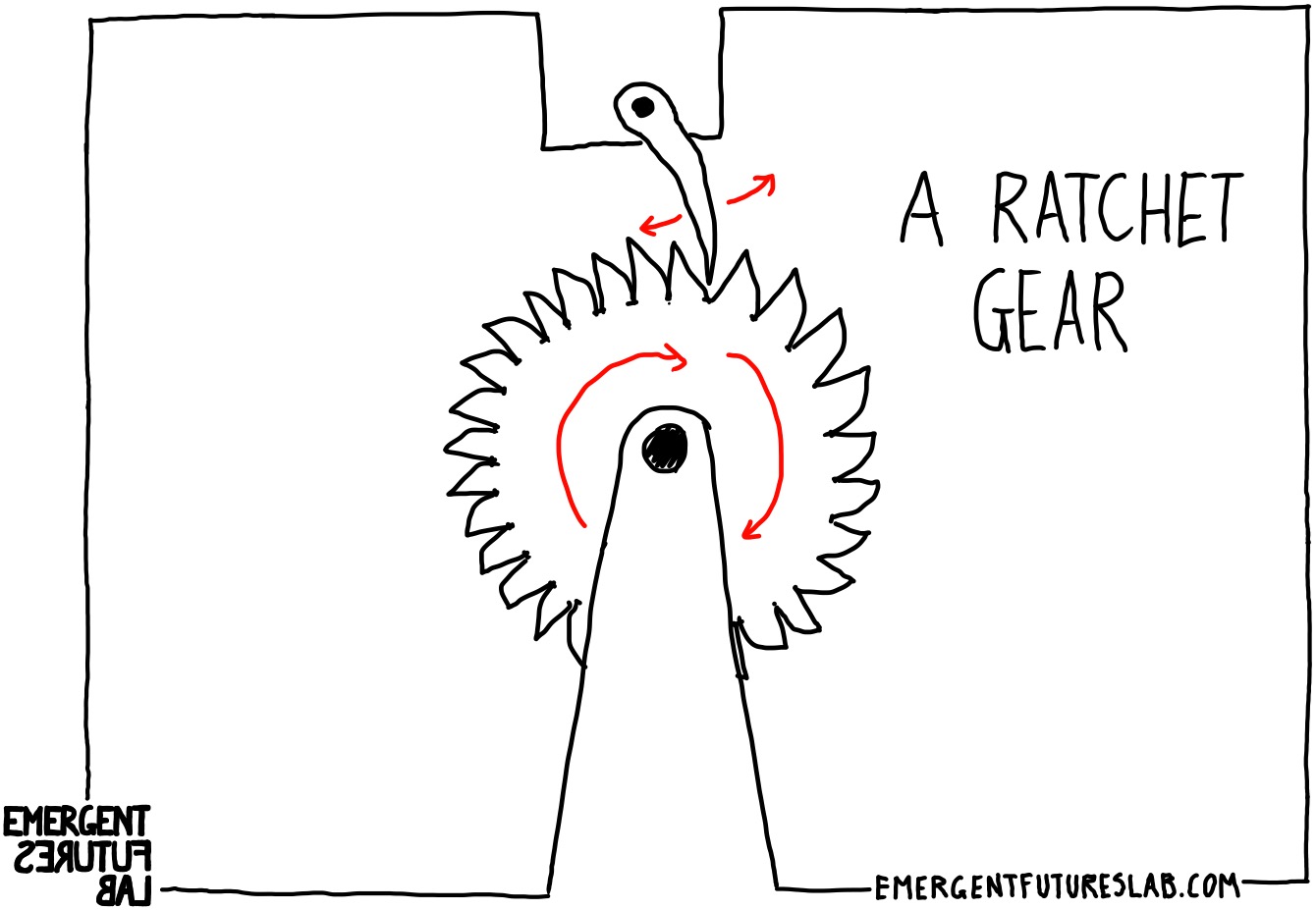

When we get into organizational contexts, the configuration of these two E’s – the extended and embedded world of tools, architectural environments, institutional habits and practices, daily job requirements, the divisions of labor, reporting structures, and feedback loops produces a very powerful set of directly experienced action-intuitions and system-wide propensity that act like a “ratchet effect.”

The concept of “ratchet effect” is critical to understanding how propensities for action (affordances) play out in concrete organizational contexts.

A ratchet is a type of gear that only moves in one direction– as the wheel turns, the arm moves to allow the forward movement but braces against the cogs of the wheel to stop it from going backwards:

And a “ratchet effect” refers to how, in many organizational contexts, because of how they are configured, no matter the input, only certain outcomes can ever be developed. In short, the system almost always moves in one direction.

Perhaps the most oft cited example of the ratchet effect in the American context is one of political organization: if there is a two party system in which one party (the “left”) tends to be the party of “moderation” and centrist in their orientation such that they always marginalize their extremes – and the other party (the “right”) tends to push towards their core which is inherently right of center – then the system can only move to the right – such that “moderation” and the “center” are on the whole ever rightward moving propensities.

Now our interest is not in deconstructing the systemic failings of any political system – these are already well documented in great detail. Rather, we wish to bring attention to an ecosystemic quality of organizations: organizations and their practices are not simply path dependent (what has been done in the past is more likely to repeat in the future). They are also organized in ways that most often, no matter what the inputs, certain outcomes are far more likely than others. We could, in relation to creativity, term this type of ratchet effect: “stable negative enabling configurations” (or what our colleague in WorldMakers, Mark Stowlow, terms “disabling constraints”).

Now it does not take radical and extreme configurational conditions to produce such ratchet effects: We see the ratchet effect of negative enabling conditions for creativity in organizations when (for example):

This is by no means intended to be a complete list.

Rather, we present these examples to highlight the ubiquitous nature of these highly directed negative propensities (in regards to creative outcomes). It takes very little to have a ratchet effect move propensities in this manner.

When we ask in an organizational context, how should we prepare to engage with creative experiments? – If we do not begin by experimentally disclosing and coming to terms with ecosystemic ratchet-like effects of certain organizational configurations, creative possibilities will simply never materialize as anything more than a cultural aspiration.

To begin organizational engagements with creative processes (and all our engagements are organizational), we first need to work diligently at a configurational level to set the enabling ecological conditions in place that would build a generic capacity for following novelty into transformational becoming. Make no mistake – this is a major undertaking. We need to consider all aspects of organizational ecosystems: the built environment, HR logics, Feedback structures, tools, boundaries, workloads, etc.

But without changing how we are Embodied, Embedded, Extended, Affective and Enactive – how we experience – we cannot open up a space for new propensities to emerge whatsoever…

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.