WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 219! Where Is Your Creativity?...

Good morning co-shaping relations with and of this activity,

It’s been a long and intense week for us – many presentations, events and keynotes on topics ranging from AI to Enabling Configurations. But, it's never all work – there were a few great evenings conversing with old friends, travelling from far shores on the enduring livingness of trees in Shinto ways of being alive. And, equally importantly, conversing on what a fingernail could become and how we escape childhood educations...

Now as the moon begins to reappear – all of this brings us to a Thursday evening becoming night – with the shoes off, the feet up, some old cheese, Kazuki Tomokawa on the record player, a glass of sour plum wine, open windows, winter winds, down pants and an old sweater welcoming the bodies heat, a phrase from Nishida: “Love is the deepest knowledge of things” floating back into memory – and the collected notes from the week for the writing of the newsletter are scattered on the dining table: it is time to give form to the newsletter…

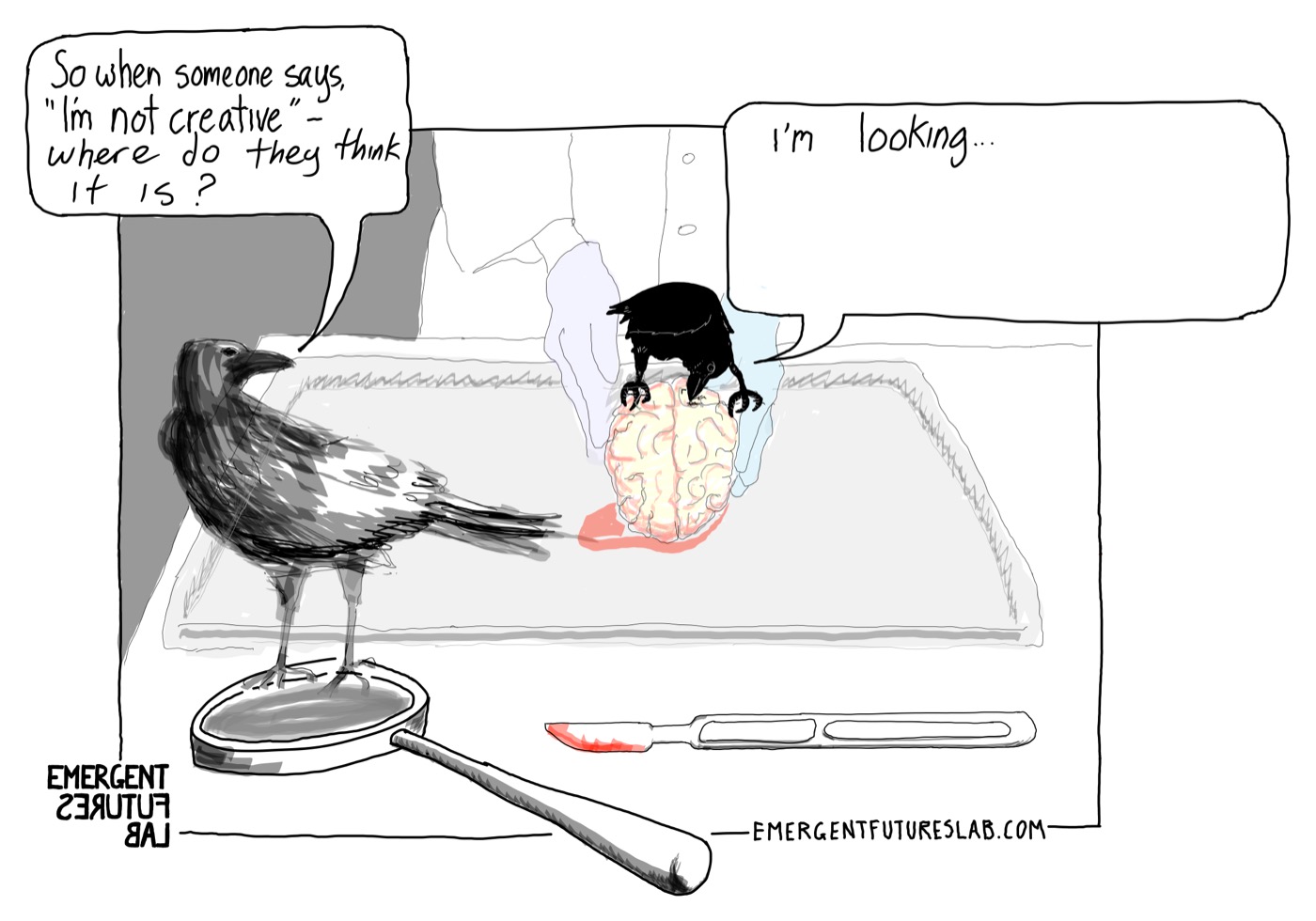

…where we reflected on a common occurrence in our workshops: When we do workshops, we will often try to begin with an informal breakfast with the participants. Almost inevitably, as we mix and talk with as many participants as possible, someone will begin a conversation with one of two statements

“I’m not creative…”

Or, “I don’t think creativity can be taught…”

To us, these answers are, on the one hand, no big deal, and they point towards a larger symptom of what is called by social psychologists a “fundamental attribution error”. This error occurs when we attribute to the individual and their character or essential identity what is better attributed to the totality of the emergent situation.

This error is a common reality – and one that we also all too easily fall into (Iain, Jason, and Andrew). It is a propensity that we recognize is quite easy – given our environment, to be pulled into. And so, we greet such discussions with the greatest of sympathy.

Additionally, we recognize that, from the perspective of creativity, this is an error that is already implicitly baked into the standard definitions of creativity.

The Oxford English Dictionary, our personal favorite of the big formal dictionaries, defines creativity this way: “the use of the imagination or original ideas, especially in the production of an artistic work.”

Now, let's take a moment to pull this apart and make visible its basic logic and how it participates in laying the ground for such an attribution error.

Here, in this definition,

These six explicit components tacitly imply a further series of outcomes:

Putting all of this together, we are led to the conclusion that creativity is some thing to be found inside an individual. Thus it comes as no surprise to us that we would get pulled into such discussions about whether creativity is some thing everyone possesses at birth or if it can be taught…

In short, the definition of creativity tells us what it is, as well as who is creative and where creativity is:

But is this the right way to approach human creativity?

Taking inspiration from one of the founding philosophers of Enactive Cognition, Evan Thompson, we like to explore this question of the what, who, and where of creativity is with an analogy to the location of “flight” in relation to birds.

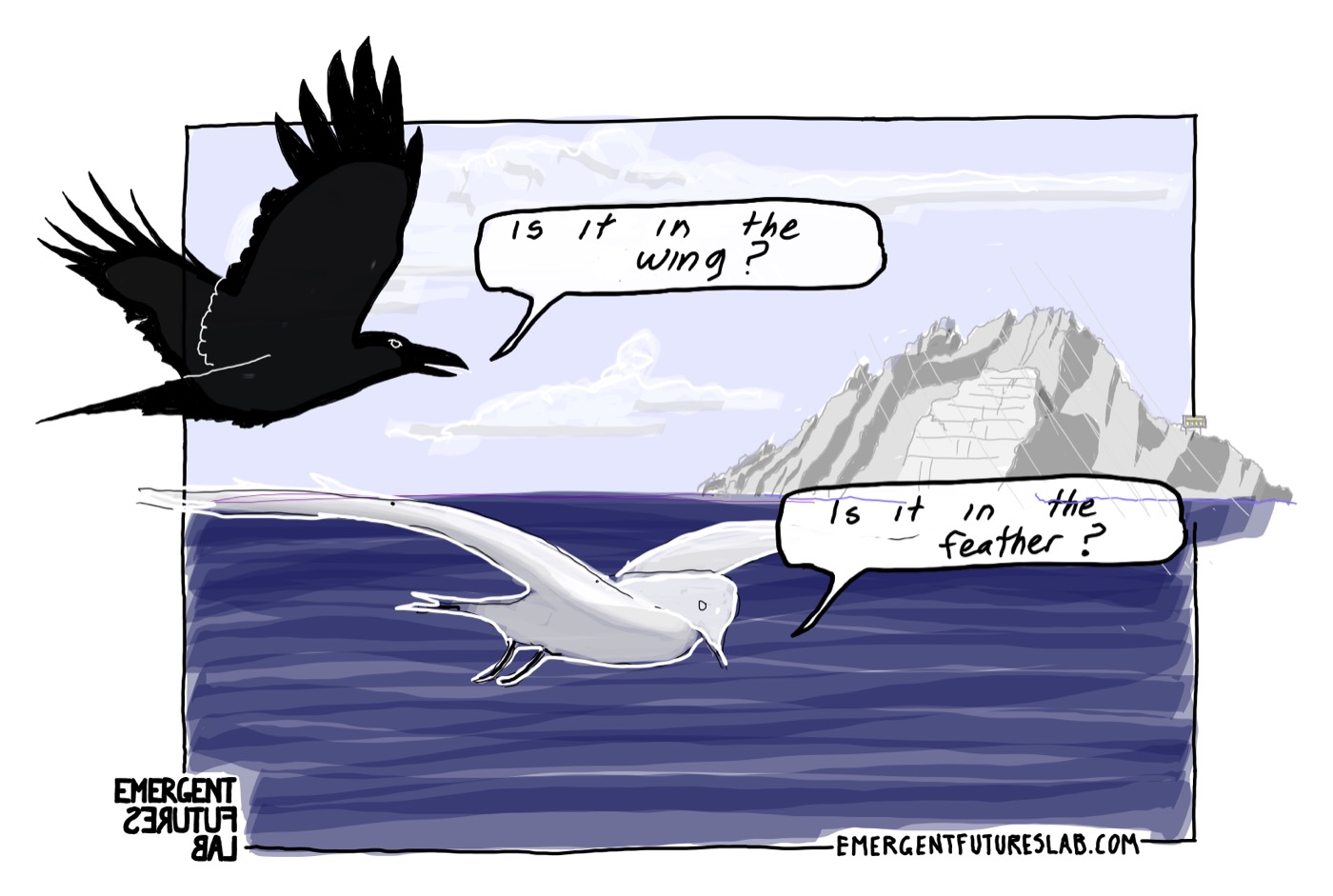

Where is flight located?

Is it in the wing? Is it in the feather?

Clearly, neither the feather nor the wing can fly alone. Remove feathers from wings or remove wings from the bodies of birds, and not much will happen.

Nor could we find “flight” in the brain of the bird. If the brain of a bird were put in a vat and hooked up to all the necessary nutritive inputs – it would not fly.

So perhaps it is in the totality of the bird?

But imagine if we could figure out how to make a bird survive in outer space – it would not be able to fly in outer space. For flight, it needs an atmosphere of a certain density that is also oxygenated to just the right amount. And for this to happen (on this planet), we need the respiration of countless plants – breathing in carbon dioxide and breathing out oxygen (and everything this entails!).

Is this then enough?

A bird and an atmosphere?

What of gravity?

What of winds?

What of the places needed to land, nest, and rest?

What of food sources?

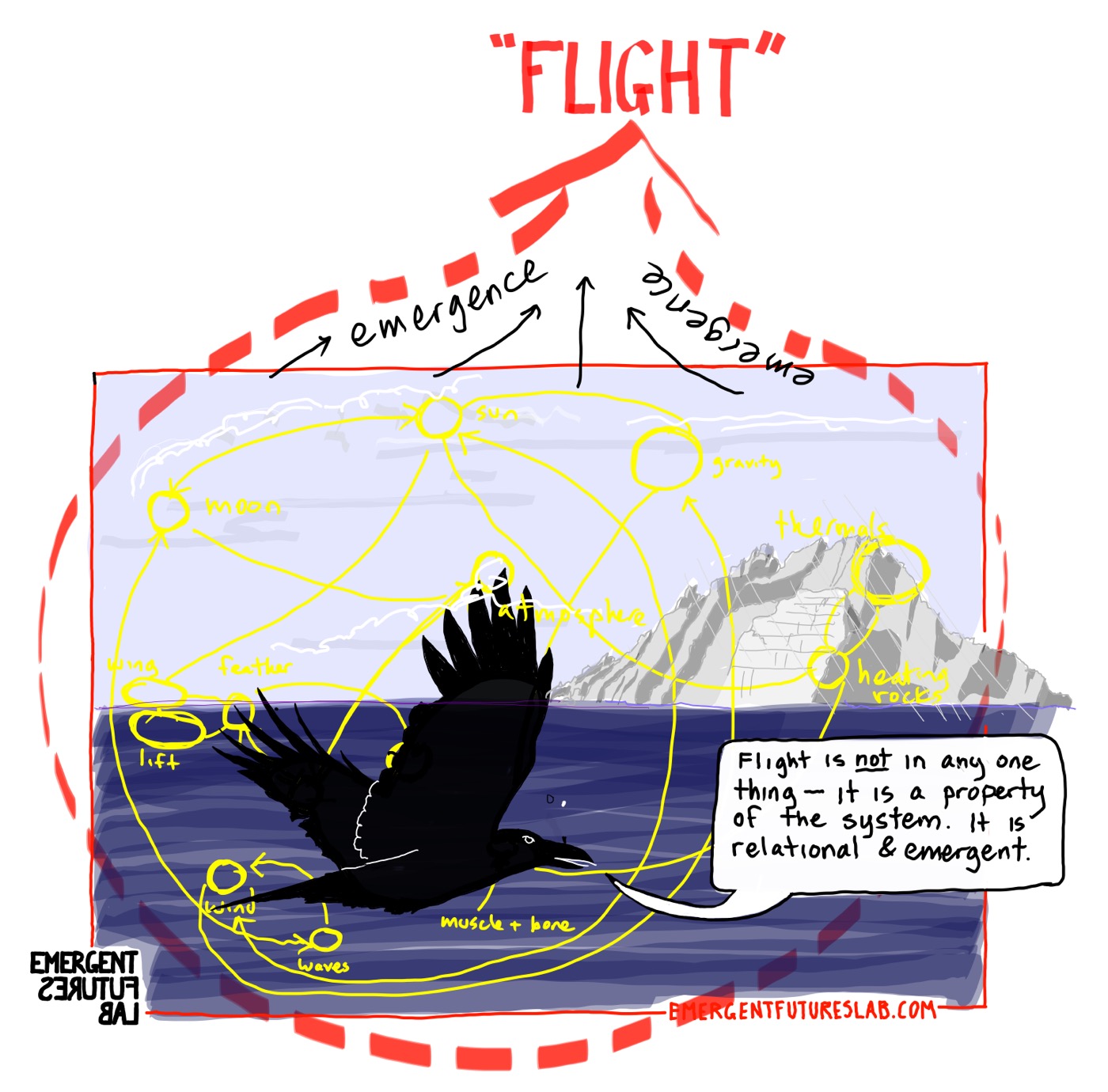

Flight is not “in” the bird – nor is it “in” anything.

Flight is the emergent relational outcome of a specific, creatively enabling and stabilizing configuration:

Now, we are not denying that for bird flight you do need the right kind of bird body, feathers, bones, muscles, and brain. In short, you do need a “bird.”

That is not in doubt. But these attributes only matter because of their relational configuration with other attributes of the environment. And because all of these attributes are relationally defined, it is the relation that takes precedence: flight is really not in any one thing – it is a property of the system – and it is wholly relational and emergent.

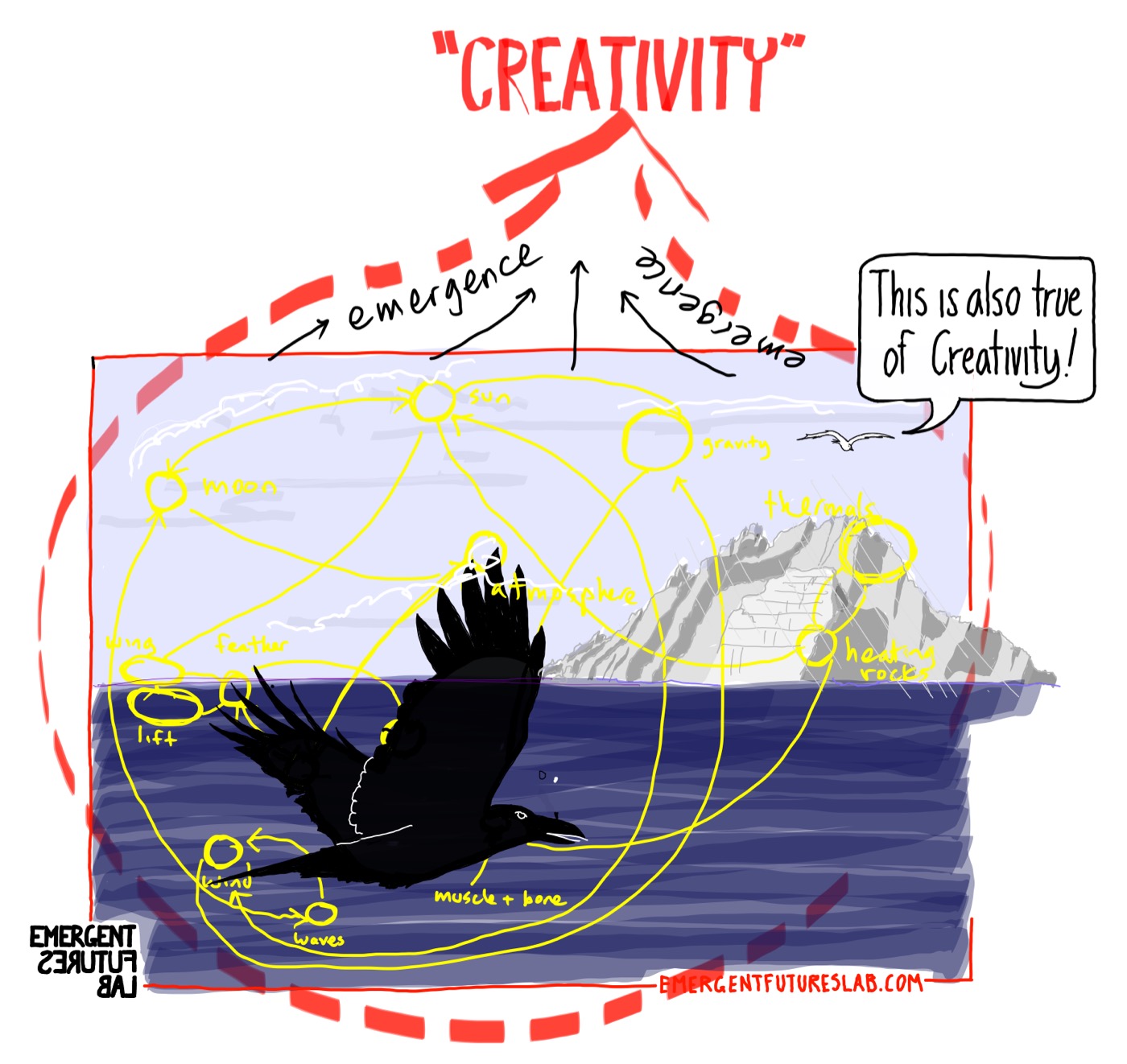

We would argue that this analogy holds true for creativity:

Creativity is equally not in any one thing – it is the relational and emergent outcome of a system.

And this brings us back to our conversation that we had before the workshops. We try to avoid entangling ourselves deeply in these questions, and strive to assure our participants that their feelings of “not being creative” or that creativity is or isn’t an innate quality – are reasonable and important – but will have little bearing on the outcomes of the workshop. And are best brought up at the end of the workshop.

Then, by the end of the workshop, everyone will have emerged from a genuine collaborative experience of relational and ecosystemic creativity. So when we explore this analogy between flight and creativity, no one tends to disagree with our ecosystem, relational, and emergent conclusion.

But – this is never the end of the story: many participants will still (quite reasonably) explain that the pragmatic thing to do as a good leader would still be to hire the best and most “creative” individual, as well as organize the environment in just the right way!

And they point out that this is the obvious conclusion of the analogy: “Even if flight is relational, and the ecosystem really matters – you would still want the best bird!”

And this reveals another deep assumption in our culture's approach to creativity that is implicit in the Oxford Definition: that creativity is one thing.

But creativity is not one thing – it is a complex process. And as such, it is a process that consists of many very, very different interwoven sub-processes. Some will involve context-specific forms of making, others critical analysis, others historical research, others interpersonal and highly sympathetic skills (and so on…). These are qualities that are highly distributed in the population, not found equally in any one individual, and profoundly co-enabled by the right situations.

The second thing about creativity's relational processes is that they loop back upon themselves. The doing shapes the doer – as the doer shapes the doing.

Strange loop upon strange loop – to such an extent that it becomes simply absurd to use terms like “nature” and “nurture” or “inside” and “outside” – and pit one against the other.

In Volume 193, we introduced one of Andrew’s favorite concepts: bio-enculturated with a discussion of the work of John Protevi on the looping between biological and the social:

The biological, bodily and the social are not separate levels “but processes linked in a spiralling interweaving at three temporal scales: the long-term phylogenenetic (we inherit a plastic capacity for living in interdependent niches), the mid-term ontogenetic (we develop our embodied capacities as we are embedded in practices), and the short-term behavioral (as developed bodies politic we act and react to our material and semiotic encounters)”. (John Protevi)

To be bio-enculturated is to exist as an inseparable weave of the biological and the cultural, where neither domain stands alone nor acts in isolation. The term signals a profound entanglement: our bodies, habits, desires, and even our sense of self are not simply given by biology or shaped by culture, but are co-produced in a living, ongoing process. We are not biological beings later draped in culture, nor are we cultural agents riding atop a biological substrate. Instead, we are always already bio-enculturated—formed in, through, and as the loops of soma and society, matter and meaning, flesh and form.

Bio-enculturation names the condition where the biological (our bodies, brains, nervous systems) and the cultural (our languages, practices, technologies, values) are so deeply interwoven that they cannot be separated without distortion. This is not a layering of one atop the other, but a dynamic, recursive process: our bodies are shaped by cultural practices from prior to birth, while those practices themselves emerge from and reshape the living bodies that enact them. We are “of things, not in them”—participants in a co-shaping that is always in the making as it makes us.

Experiences and Situations

And all of this brings us back to the question of a “fundamental attribution error.”

How often have you found yourself pulled into a conversation about why someone does a job well or poorly via the reference to some trait that it is imagined that they possess? We certainly have…

This is no different than the cultural assumption that creativity is a thing – a trait – that someone could or could not possess.

And far too many organizations hire, judge, and train employees based upon a trait-based approach to job aptitude. (The research suggests that this is over 80% of fortune 500 companies). Which is to say, they claim that the best way to understand what we will do and who we are in a situation is via the understanding of our internal and underlying personality traits (such as the so-called big five of Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism etc.).

The belief in traits is a type of cultural conceptual zombie – it just will not die no matter the evidence.

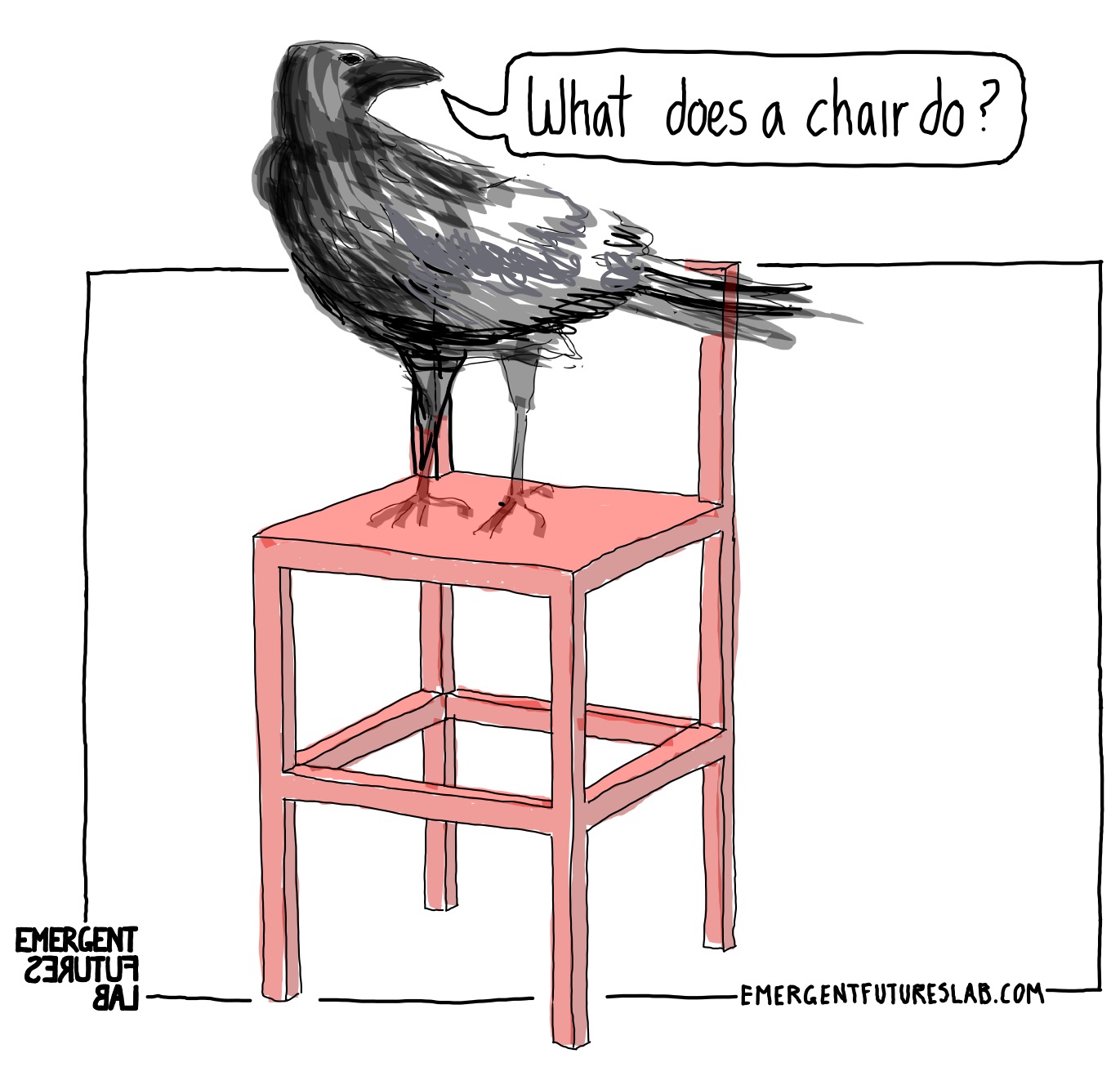

In the last two newsletters, we shared research on the role of the humble chair in co-creating our judgements: The hardness or softness of a chair, in the right context, will co-shape a judge's determination of what severity of sentence to render. This should give us pause. Is our behavior – our judgment in this case – really simply because of some internal trait?

Should we speak of deep inherent honesty, a sense of fairness, and the ability to reason…

Should we speak of a deep, inherent individual thing clearly leading to the outcome?

The research on this question is vast and overwhelmingly clear: our actions are profoundly emergent, relational, and ecosystemic.

Not only is the research overwhelming, but it has given rise to the disciplines' social and situational, environmental, and ecological psychology (amongst others). And within these fields has emerged a vast body of research on how the qualities of the situation play a profound role in co-creating our actions. The rightly famous research of Stanley Milgram, Philip Zimbardo, Hanna Arendt, and Zygmunt Bauman demonstrates how highly diverse and psychologically normal individuals will act to do everything from delivering permanently harmful electro shocks to the most caring assistance because of situational and environmental factors.

To cite one more example we appreciate: One of the great classical experiments investigating these qualities is the “good Samaritan experiment,” where the psychologists John Darley and Daniel Batson set up a situation where participants were either late or had time to get to an important meeting. And on the way to the meeting, they are met by someone in need of serious assistance. Their willingness to help was found to be predicted by time pressures and not other qualities. And this is only one of a myriad of profound experiments that demonstrate that to be human is to be ecological.

The research shows that what is co-shaping our modes of acting and sensing is situational. Why we do what we do cannot be explained or predicted with any accuracy (except at the very largest of sample sizes with the most general of outcomes) via the understanding of traits ( The research into this has a long history from American Pragmaticism to Kurt Lewin to Environmental Psychology, Social Psychology and beyond (and is certainly worth exploring in depth – but is beyond the scope of this newsletter).

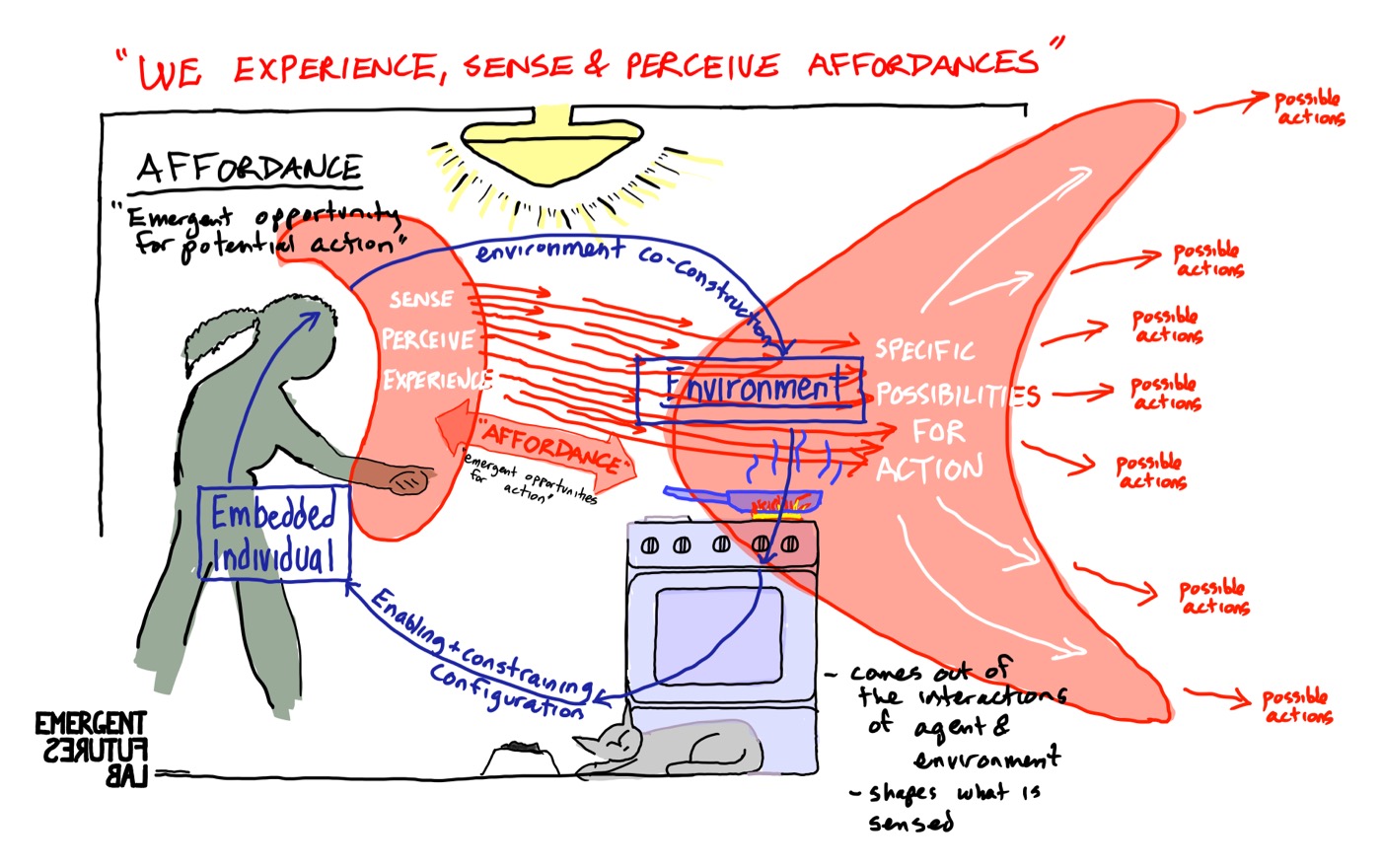

In our last newsletter, Volume 218, we explored how our immediate and direct experience, perception, and understanding in a situation (what it “affords”) – is the emergent outcome of an engaged relational practice – how we are bio-enculturated.

Putting all of this together, there should be little doubt of the immense importance of paying attention to the relational contextual circumstances of our actions.

This newsletter is the fourth in our series exploring and experimenting with the question:

How should we prepare to engage with creative experiments?

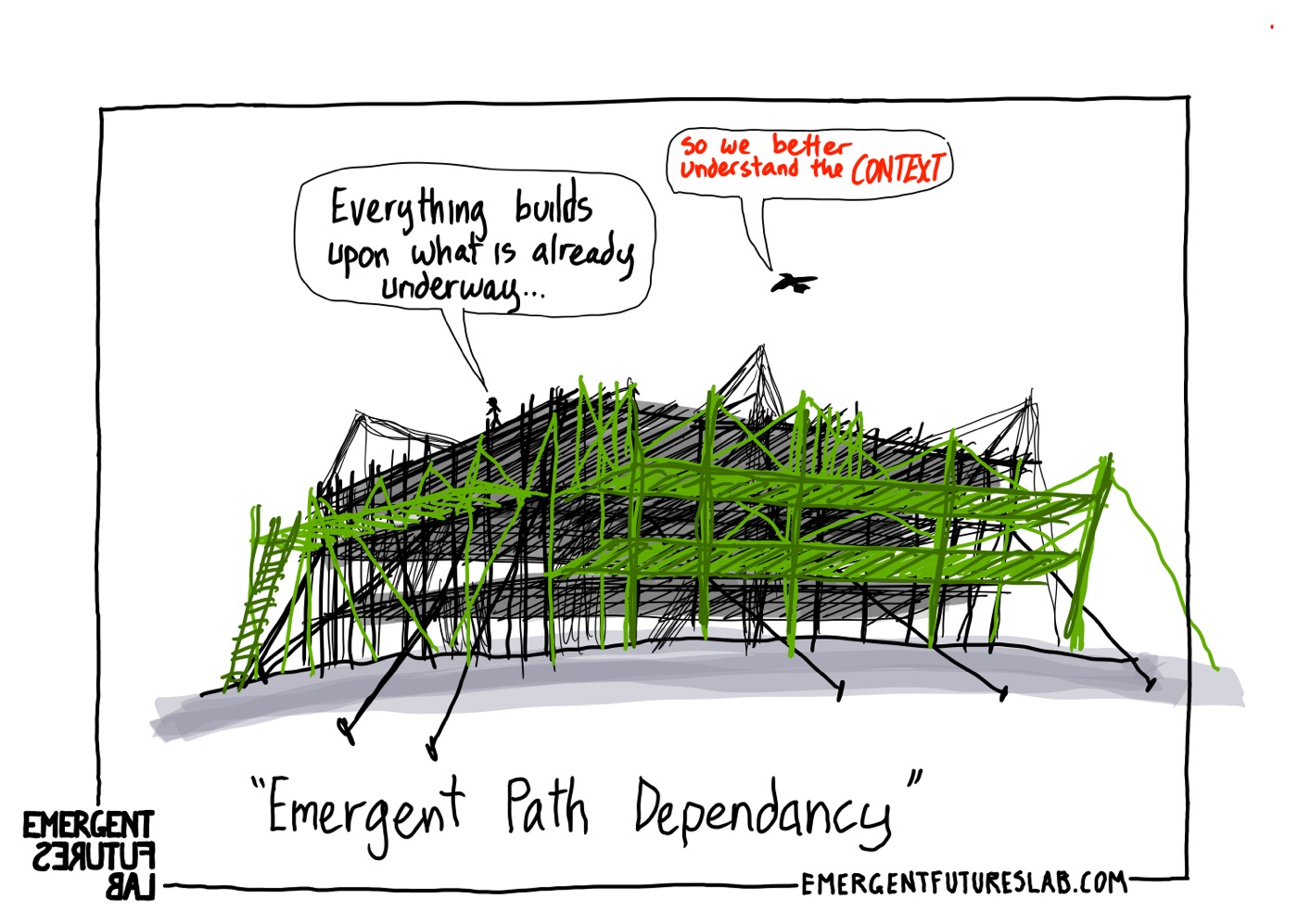

And as we have been stressing over the last three newsletters, the agency of the context cannot be ignored…

And this week, the newsletter is motivated by the desire to critically challenge an all too common answer: hire the most creative individuals, inculcate a creativity mindset, and develop a supportive creativity culture.

Our hope is that you see the absurdity of such an approach...

Our question in such a context is always: What is “leadership” when the ecosystem is always already leading?

Last week, our answer to this question, as we ended the newsletter, was what might feel like a daunting challenge:

“To begin organizational engagements with creative processes (and all our engagements are organizational), we first need to work diligently at a configurational level to set the enabling ecological conditions in place that would build a generic capacity for following novelty into transformational becoming. Make no mistake – this is a major undertaking. We need to consider all aspects of organizational ecosystems: the built environment, HR logics, Feedback structures, tools, boundaries, workloads, etc.

But without changing how we are Embodied, Embedded, Extended, Affective and Enactive – how we experience – we cannot open up a space for new propensities to emerge whatsoever…”

This week, we wish to end on a hopeful note – we humans have far more watery relational souls than is often imagined, and when we really deeply care for the ecosystemic conditions we find ourselves in, we can produce conditions conducive for the emergence of creative outcomes.

When we come to understand creativity – and selfhood – as a complex multidimensional thicket of interwoven and distinct processes leading to emergent outcomes, we can move away from the ethically problematic intense scrutiny of individuals for imaginary “traits” – and begin to collaboratively build creative life-affirming, enabling, and stabilizing configurations.

This week, let's take respite, solace, and creative courage from the fact that we are intra-dependent configurational beings – more dynamic webs than infinitely distanced neutron stars…

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.