WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 221! Creativity: Thick and Wide...

This week – it’s the end of the beginning so to speak: it’s the final week of our series on “How to prepare to begin to Innovate” – the tasks that we like to term loosely “Engage”.

Over the last five newsletters, we have been experimenting with this question from various perspectives:

As we come to the end of this series, we do not wish to summarize or neatly package this topic. Why not? It feels that we live in a world where this logic of summary and neat packaging has become all too ubiquitous and frustratingly stupid with the rise of AI. At every turn, we find ourselves facing neatly packaged view-from-nowhere summaries.

Everywhere we turn, these stochastic parrots repeat: “Here – this list of bullet points – this is all that it means…”

Andy Warhol was far too generous when he imagined that each of us would have “our ten minutes of fame” – now he is, a googles AI summary informs us, six elegant bullets:

This is what he means – in less than thirty seconds of reading…

But meaning does not work this way – it is never generic, it is never a view from nowhere – despite what it might seem.

Meaning begins in creative engagement. And this form of engagement – the activity of coming to (a novel) meaning – requires something very different and far more open and experimental of us.

Remember, as John Cage points out, “It is only experimental if we do not know the outcome”. And if we can summarize it without doing anything, then it is not an engagement.

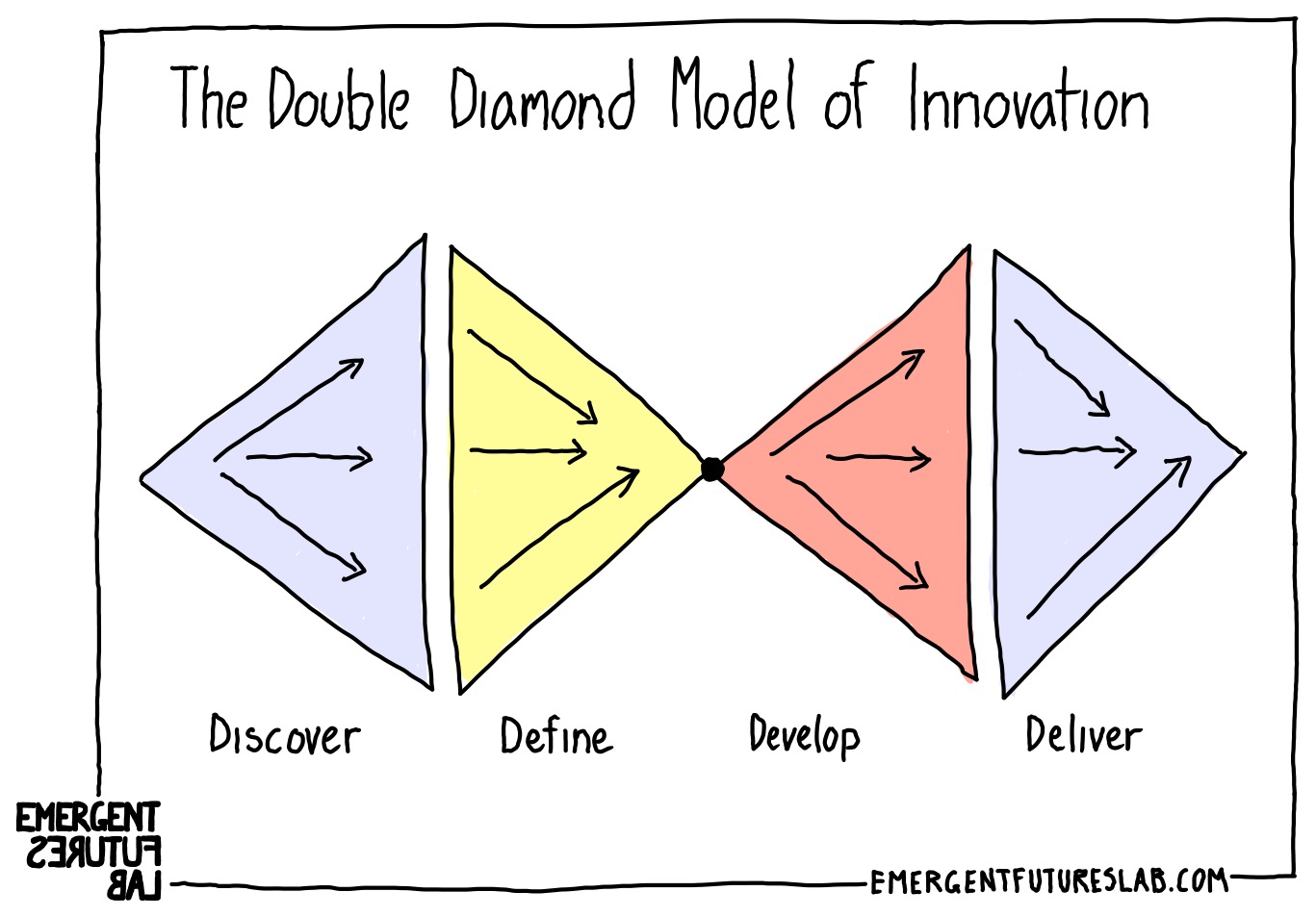

And it is because of this that we have deliberately chosen this word – “Engage” as a way to describe the early activities of creative actions. We use it to strongly contrast with how the early aspects of creativity are far too often framed. Too often, approaches to innovation begin in what feels like very disembodied and highly abstract practices: Research, Discover, Define, Empathize, Imagination, and Ideation. All things that could be easily carried out, summarized, and effectively bulleted by your favorite AI tool.

This is very much the contemporary world we live in – when the prompt comes: “be creative” the habits, rituals, practices, concepts, tools and environments are already configured towards board rooms, flip charts, whiteboards, sticky notes, interviews, questionnaires, and now AI – these are the ecosystems that kick into high gear (see Volume 218).

And it is in this very real and problematic context that we, like this term, engage to reframe the beginning of a process that engages creative becomings because it reminds us that everything comes from and cycles back into actions – engagement (see Volume 216).

Engagement is not some added extra. It is not something we do after we have figured out a plan. Engagement is not a form of late-stage product testing – it does not come after we have figured everything out conceptually (see Volumes 219 and 220). Here we take a strong embodied sense of direction from the works of a pioneer of enactive cognition, Humberto Manturana, who said,

“To live is to know.”

Such a seemingly simple statement – but one that is so radical, especially today. Without the condition of being alive, there is no knowing – no meaning – no intelligence.

To creatively come to “know” anything whatsoever requires that we participate in things as precarious contingent beings. While we certainly feel that this is a universal truth, we don’t say this generically. In this nascent age of AI, it is more relevant than ever to stress that meaning, knowing, and intelligence are ultimately not something wholly abstract and accessible to algorithmic statistical pattern recognition. It takes a unique engaged creative act that is fundamental to living and only to living beings.

While Artificial “Intelligence”, which is, as Johannes Jaeger argues, more aptly termed AM – Algorithmic Mimicry, can effectively mine tightly circumscribed realms for patterns (see Volume 138). Meaning lives and emerges from open, nebulous, and very hard to define lived experiences. So while AI can work with clearly defined problems and parameters, life and creativity live within the reality that nothing we do will turn out the way we think, imagine, know, or can predict.

We are fated to engage things from one perspective and follow things in ways that will always exceed what we predicted and that will ultimately co-emerge in ways that exceed the knowable.

Surprise is our creative fate as living beings. Only “to live is to know”...

Unfortunately for AM (AI) and our hopes of a rational and linear world: creativity begins with the realization that no so-called problem or question or occasion is what it seems...

Over the last few weeks, as we have discussed and experimented with this topic of “what should we do to prepare to begin to innovate?” – and this has led us to think a lot about the question of relevance and creativity: how do we come to decide/create what is relevant? (See Volume 217). The emergent creation of relevance precedes and gives rise to meaning and knowing.

This is something we raised in our community of practice, World Makers this week: with the seemingly simple question: what comes before knowledge?

What is the creative process that leads to knowledge? (It is also something that we experimented with in Volume 218: Engagement: Stepping into the River we are already in).

When we engage with things – when we do things – we meet a creative relational reality as neither objective nor subjective – it is neither fully separate from us (objectivity) nor is it reducible to us (subjectivity). Rather, we are of it – and it is better understood as what Veraeke and Mastropietro term “transjective”.

“What is relevant to an organism in its environment is never an entirely subjective or objective feature. Instead, it is transjective, arising through the interaction of the agent with the world. In other words, the organism enacts, and thereby brings forth, its own world of meaning and value.” (Jaeger et al).

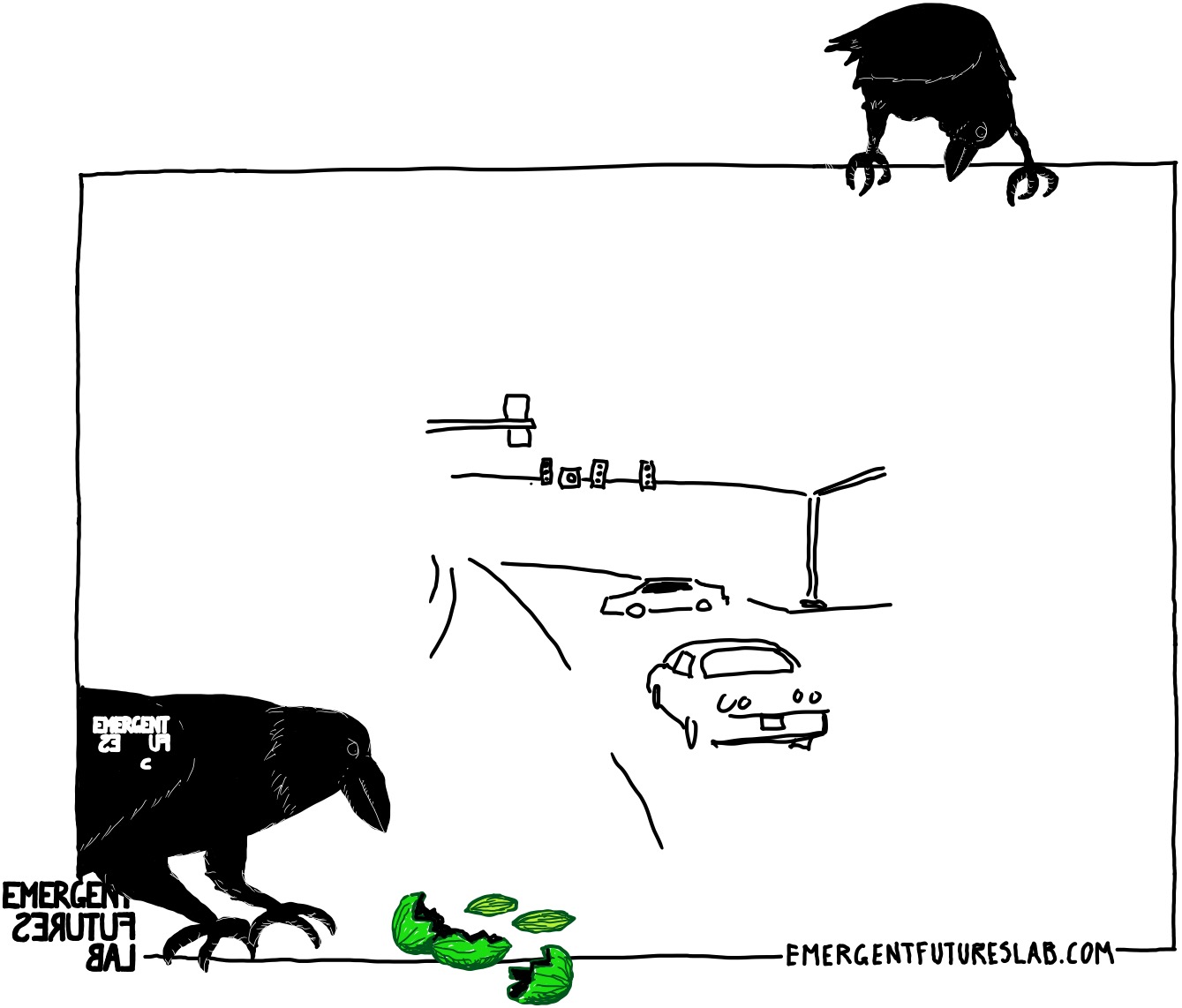

An example: If you think about the crow story – our favorite one – where they are using an intersection with a traffic light to crack nuts. The reason that we humans do not see the intersection as affording nut-cracking possibilities is because it’s not relevant to us.

Relevance makes things show up for us in the way they show up. This happens because we are precarious, specifically embodied beings that always find ourselves in a concrete environment with some general active concern. For example, we are biking down the street – now that crack, bump, or pothole shows up as relevant and significant in a new and very real manner.

This is equally true for the crow. When they have a nut in their beaks, the world looks and feels different. Now the car shows up as relevant in a new way. Now the traffic lights show up in a new and relevant manner.

Relevance is created and realized by our exploratory actions in a context. Relevance is not something objective or subjective or pre-given. It comes into being via our embedded actions. Relevance – and from it, meaning – and from this, knowledge – is all a transjective creation of an engagement.

It is highly context sensitive. It is a fundamental form of our mundane everyday creativity. It’s a creativity you sense and see when you are in the thick of some activity – how you improvise in nursing your baby, cutting vegetables, or rushing across the street in the rain. Your elbow just turns inward to cradle your baby's head. Your knife and wrist spontaneously change angles with the softness of an eggplant. Your feet find a unique purchase on the crack in the sidewalk to push off in a way you would never have considered – or noticed. A word comes out in a new way in the middle of a deep conversation…

It is a critical aspect of creativity that cannot happen outside of action – outside of engagement. To engage with this critical aspect of creativity requires that we do things. Which is why we love the axiom from John Cage that Bruce Mau articulates so well in his Incomplete Manifesto for Growth:

“BEGIN ANYWHERE.

John Cage tells us that not knowing where to begin is a common form of paralysis. His advice: begin anywhere.”

What matters is that we begin – we do something. We engage. But it is more than that: for creativity, we need to show up in a very unique manner: We need to “act like crows” – we show up with a nut in our beaks in an odd context (so to speak). And now novel things begin to happen – to become relevant.

Our creative lives involve relevant invention and, more importantly, creative relevance switching.

Think again of our crows – cars already had a relevance to them, perhaps in how cars skillfully killed creatures that they could then pick at and eat from the relative safety of the side of the road (the glories of roadkill). And the powerlines and traffic lights also had a relevance to the crows as safe places to perch and observe roads for roadkill. The move to cracking nuts involves an experimental creative activity of relevance switching: once the crow has a nut in its beak, now the stopping and starting of cars has a new and quite different emergent relational relevance – different qualities spontaneously emerge as relevant in the midst of this new event.

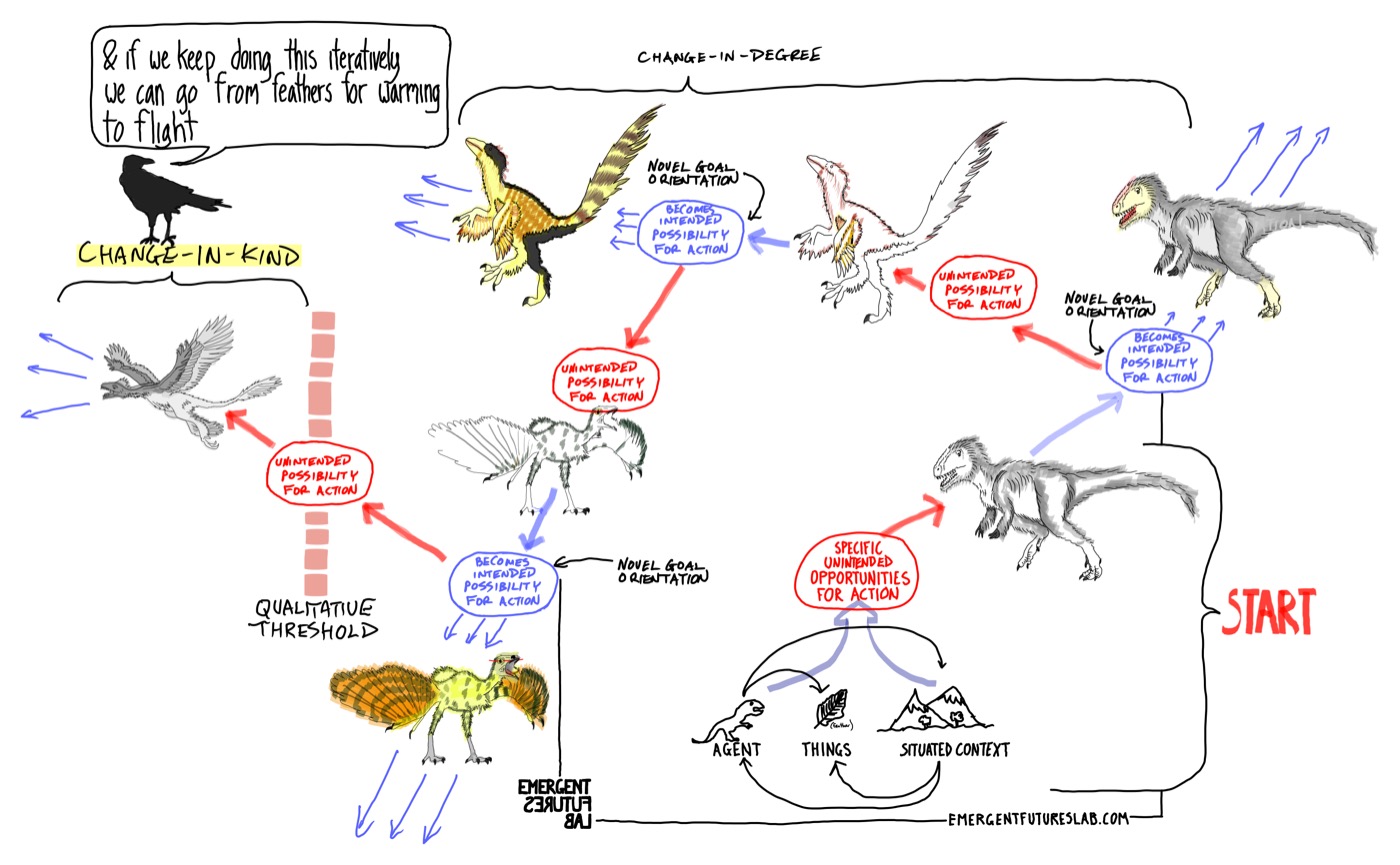

We see this iterative making and changing of relevance in the story of how a dinosaur becomes a bird:

– or how the Wright Brothers invented wing warping:

This story is worth retelling: Very early on in their experimental interest in flight, the Wright Brothers were experimenting with box kites, trying to develop a way for pilot-based control to work, and all the while working in their bike store.

While changing a bike inner tube and chatting with a customer, Wilber is fidgeting with the inner tube box sleeve – twisting it. And then, mid-conversation, it strikes him that this twisting of a box is how a pilot could control a glider.

The twisting of the box sleeve becomes relevant in a totally new manner. It is this mix of having a general concern plus doing something in an odd context that leads to novel relevance creation.

Now the box and how it twists becomes relevant – meaningful, and a concept can emerge. Here, engaged experimental making is thinking. And what is made in the doing is novel sense-making via relevance creation. E.g., Now the Wright brothers can actively and experimentally make sense of the question: what is pilot control with a box kite? Sense is being made – both physically in a new design and conceptually in a new set of concepts…

Of course, once relevance is fully realized, it becomes established as something that could be explicitly stated or translated into forms of knowledge. Now we can talk about a clear concept, e.g., “wing warping.” But this knowledge tells us nothing about how it came to be realized…

“Contrary to an algorithm, the most sensible… course of action for an organism does not simply follow from logical rules of inference, not even abductive inference to the best explanation. Before they can “infer” anything, living beings must first turn ill-defined problems into well-defined ones, transform large worlds into small ones, and translate intangible semantics into formalized syntax... And they must do this incessantly: it is a defining feature of their mode of existence”.

This process is called relevance realization…

Organisms actively explore their world through their actions. For an organismic agent, selecting an appropriate action in a given situation poses a truly formidable challenge. How do living systems—including us humans—even begin to tackle the problems they encounter in their environment, considering that they live in a large world that contains an indefinite (and potentially infinite) number of features that may be relevant to the situation at hand? … It is not simply the external physical environment that matters to the organism, but its experienced environment, the environment it perceives, the environment that makes a difference for choosing how to act.. In other words, the organism enacts, and thereby brings forth, its own world of meaning and value… This grounds the process of relevance realization in a constantly changing and evolving agent-arena relationship, where “arena” designates the situated and task-relevant portion of the larger experienced environment… (Jaeger et al – this essay was very inspiring to the whole of this newsletter)

Life – creativity – is an experimental engagement – because it can never be anything else. All our actions – all our engagements are a play with novel situated concerns – curiosities – in environments that only come to be what they are (which is neither subjective nor objective – but very real) because of what we collectively and collaboratively do.

But to end our discussion of the profound importance of engagement here would be to miss the critical distributed nature of the agency of our actions. We become who we are as creative beings in and of a rich, thick, entangled, diverse configuration (see especially Volume 219 and the discussion of the Fundamental Attribution Error in Social Psychology).

Over the last week, I have been reading Brian Merchant’s astonishing history of the iPhone: The One Device: The Secret History of the iPhone. We in EFL tend not to read much about Steve Jobs or Apple because it is far too often written from a narrow and profoundly parochial perspective. But I (Iain) was reading Merchant’s other brilliant and critical book, Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech – a deeply informed and insightful new and challenging history of the Luddites (I was reading it as part of critically thinking our way into the vast ecology of impacts AM (AI) is participating in).

All that aside, what is remarkable and relevant to this discussion of how we prepare to begin to engage with creative processes, Brian Merchant cuts through all of the origin myths – and we get to something like the real story of now novelty emerges and what is happening before the beginning:

“Like many mass-adopted, highly profitable technologies, the iPhone has a number of competing origin stories. There were as many as five different phone or phone-related projects—from tiny research endeavors to full-blown corporate partnerships—bubbling up at Apple by the middle of the 2000s. But if there’s anything I’ve learned in my efforts to pull the iPhone apart, literally and figuratively, it’s that there are rarely concrete beginnings to any particular products or technologies—they evolve from varying previous ideas and concepts and inventions and are prodded and iterated into newness by restless minds and profit motives. Even when the company’s executives were under oath in a federal trial, they couldn’t name just one starting place.”

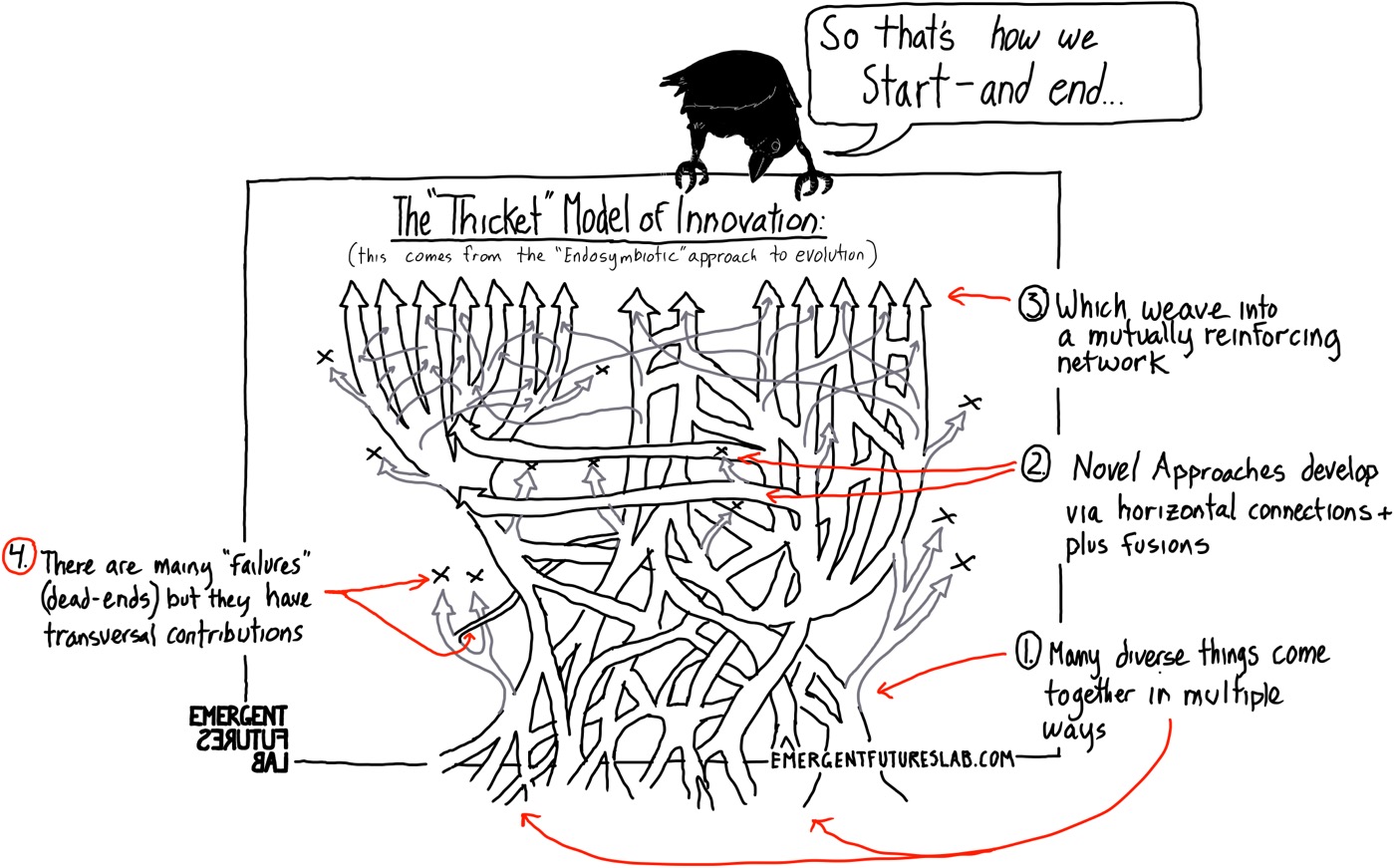

When we ask the question: How should we prepare to begin to innovate? The answer is that innovation begins thick and wide. It is never one thing, one idea, one experiment, or one person. It is going to emerge from an already ongoing dynamic, rich, diverse, and deeply horizontally entangled ecology where novel possibilities of new relevance realization can co-emerge in startling ways.

It will never reduce to a single point (as the double diamond approach to creativity might imagine). But instead, it will be the thick and wide transformation of many entangled ecosystems – ultimately without end.

The question is not how to have a great idea or imagine a revolutionary outcome. No, creativity asks us to collectively engage in ways that find, support, develop, collaborate, and co-evolve with an already existing transversal thicket such that it can configure in ways that can spontaneously allow for the co-emergence of novel adventures of relevance realization.

Have a joyous experimental, astonishingly wide and thick week entangling into and with ongoing novelty towards new transjective relevance realizations…

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.