WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 196! Creativity Dreams of Intensities Beyond Systems...

Good Morning lively beings in the mi(d)st of becomings,

Here it has been raining again, thick clouds low to the ground, a wonderful all-pervasive dampness–

In the fifth-month rains

no trace of a path

where I can make my way,

meadows of bamboo grass

awash in muddy water

~ Saigyo + B. Watson (translation)

Then in the afternoon it clears, and the next morning dawns with falcons screeching on what promises to be a hot and sunny ever intensifying day. Kids playing soccer in the streets, and traffic building up all around. And for no reason we come across these words:

…I will do lovely things in taxis

and count myself among the lucky, I will

comb the pale hair of boys with muttering

hands wanting only the satiate fact

of that silk, I will discuss perfidy

with scholars as if spurring kisses, I

will sip the marble marrow of empire.

I want sugar

but I shall never wear shame

and if you call that sophistry

then what is Love

~ from Debbie: an Epic, Lisa Robertson

We’ve been mentioning we have a special anniversary coming up on July 11th, we will publish our 200th Emerging Futures Newsletter! And because of this, to celebrate our two hundredth issue, we would like to publish some personal reflections from you, our readers, on what the newsletter has meant to you.

If you wish, please take a moment to email us a reflection – it could be in any format (a letter, a video recording, an audio file, a drawing, a photo). And it could be any length – short or long. For our 200th issue, we just want to focus on you and what you have done with it.

This week, we continue our engagement with “Systems Thinking” and its relation to creative practices. Last week, we looked critically at how it deals with – or to be more blunt: does not deal with the radically contingent nature of reality – with surprise.

Some might say that things get messy, but that gives too much attention to the illusions of neatness. We prefer to recognize that life is lively – the surprise of the new and the surprise of the same is what it does. Its regularities are not the moments it relaxes. Everywhere and at all times, there is creative activity. Being similar and stable takes enormous creative work. How could we ever assume otherwise? Why is effort associated with transformations, and little or no effort associated with things staying roughly the similar?

Regularity is not the revealing of some deep set of stable structuring essences or the deep unchanging effortless identity of some underlying causal thing. No, what is seemingly unchanging is equally a contingent state acquired and maintained with great and ongoing lively creative effort. Think for a moment how much ongoing beautiful creative engagement it takes to keep a house or your personal being in becoming.

This week, we want to build upon this to bring a critical curiosity to the question:

Before answering this question, we want to clarify our reason for critiquing Systems Thinking – first, there are many critiques out there that focus on the practical problems with the approach:

And additionally, from the universe of business consultants dabbling in Complex Adaptive Systems, it can be easy to dismiss all Systems Thinking out of hand as quaint, reactionary, and irrelevant. Like we said of a stopped clock – it might be hypothetically right twice a day, but it is never helpful…

We are not interested in either of these positions. While we do fundamentally disagree with Systems Thinking, when we re-read Donella Meadows' wonderful book “Thinking in Systems: A Primer” in preparation for writing this newsletter series, we found that there is much that we would, from a very pragmatic perspective, fully agree with. Her final chapter, Living in a World of Systems, offers fifteen helpful suggestions:

Now we would agree with much she offers here, as well as disagree with her answers to some of these – and yes, some of these disagreements would be profound – but what a helpful reminder of where to focus!

Our critique is from a systemic perspective – everything is process, everything is relational, and everything involves emergence’s strange loops. But what this means is difficult to grasp without falling back into historical approaches that profoundly misrecognize what this might mean. We are still in the early days of developing this approach out of the essentialist Greco-Christian traditions. This is an exciting emancipatory project that connects to many other traditions and approaches globally that have a much longer and far richer engagement with these propensities. We imagine our work as an experiment in this collective endeavor.

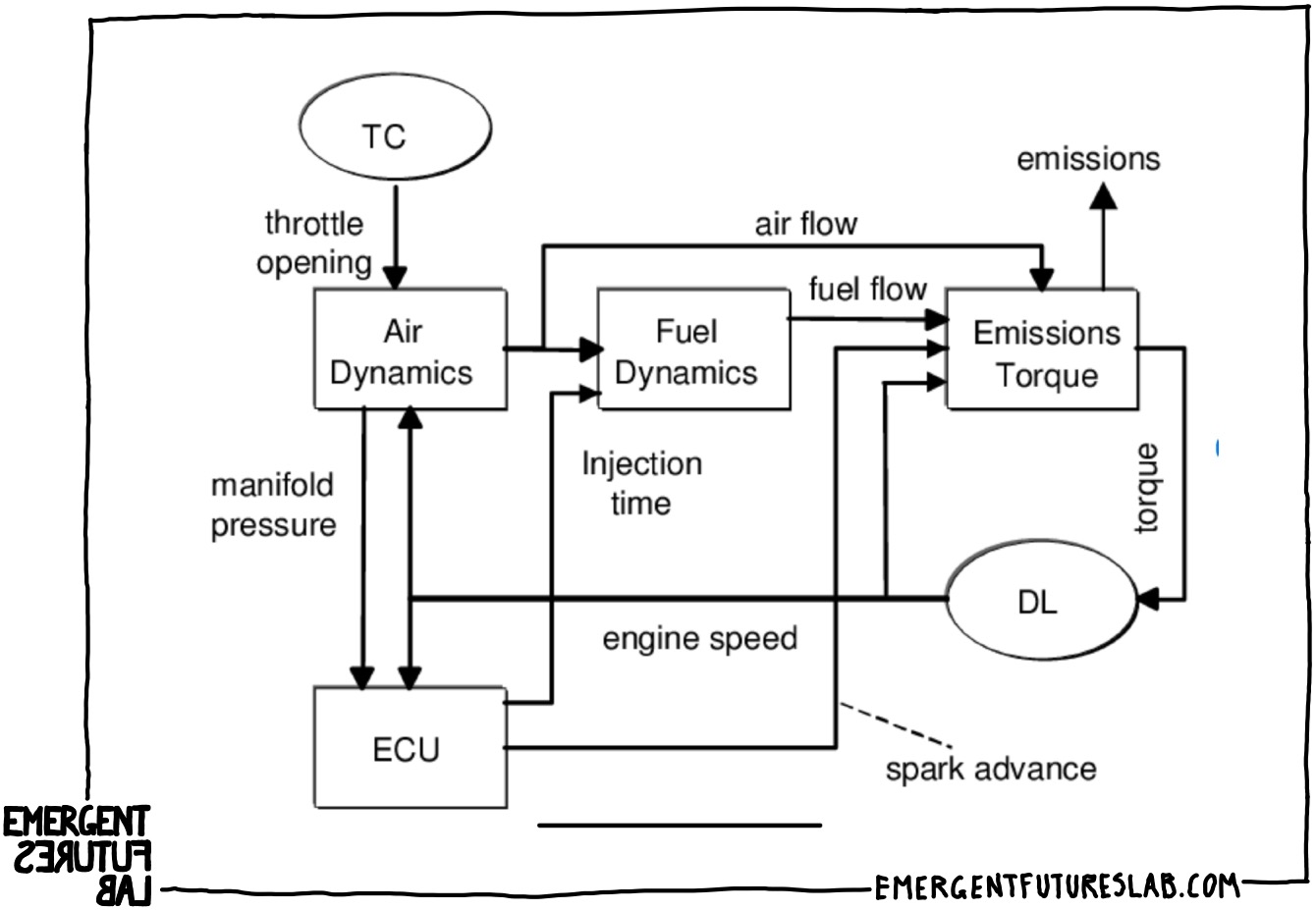

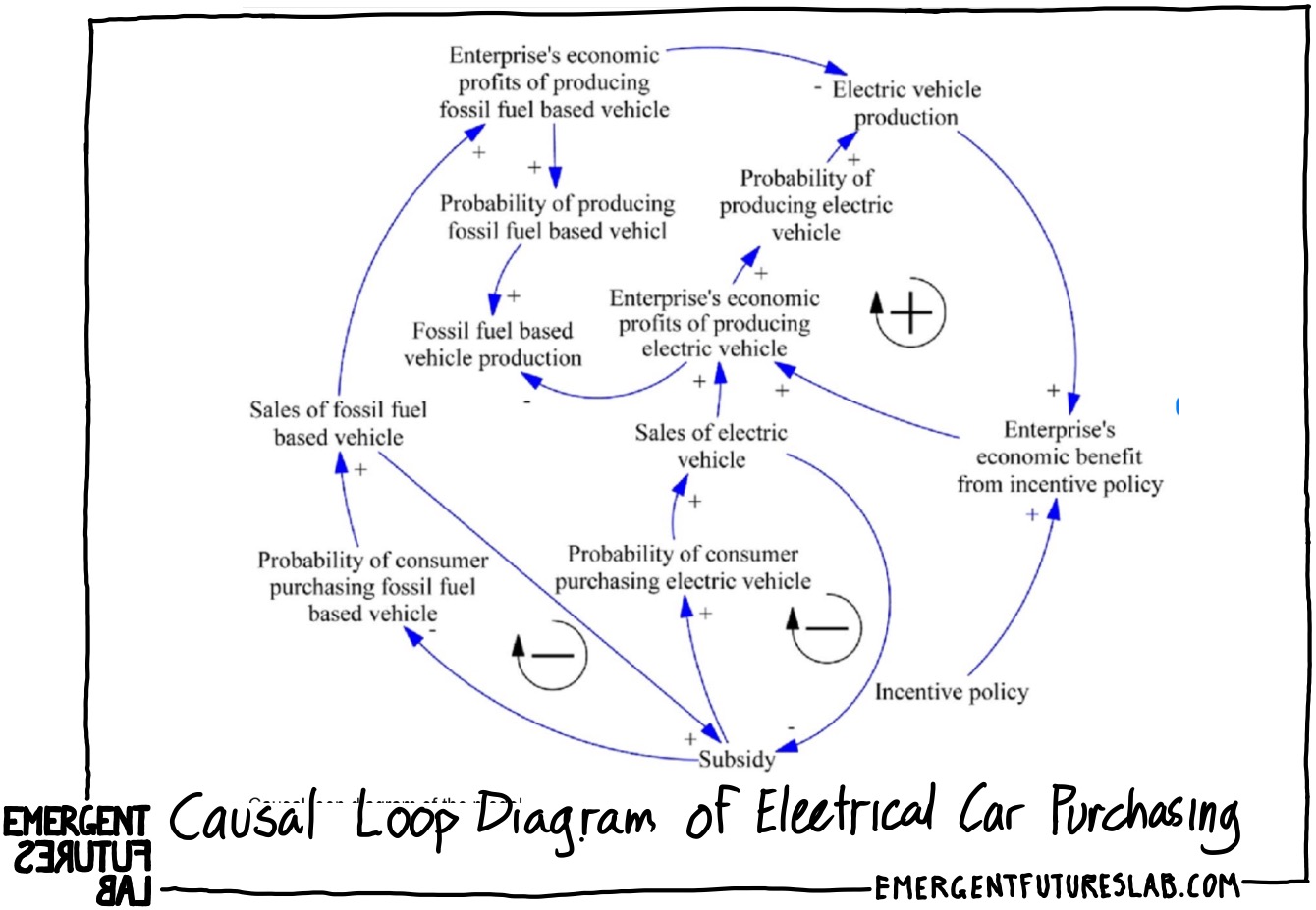

Systems Thinking, or what is it is more accurately called Systems Dynamics, is perhaps most well known and used for how it maps, really diagrams, to engage with “systems”. The goal of these maps – or what are called “causal loop diagrams,” is threefold: to understand how a system functions, which is to say what causes what, and then how we might be able to work with the system to bring about change. It is thus in the most general sense an approach to creativity – change making.

So how do things function – cause a regular outcome according to this approach? Let's start with a simple example: We can understand how an engine functions, and we can accurately diagram this:

/

In such a diagram, each component has a given, fixed, and usually singular function. The function of the piston, for example, is to convert high pressure/heat into an up-and-down motion. And the piston is connected to the crankshaft via a rod, which converts the up and down motion into rotational motion. And the crankshaft rotates, and this rotation causes the wheels of the car to turn, and this turning moves the car forward.

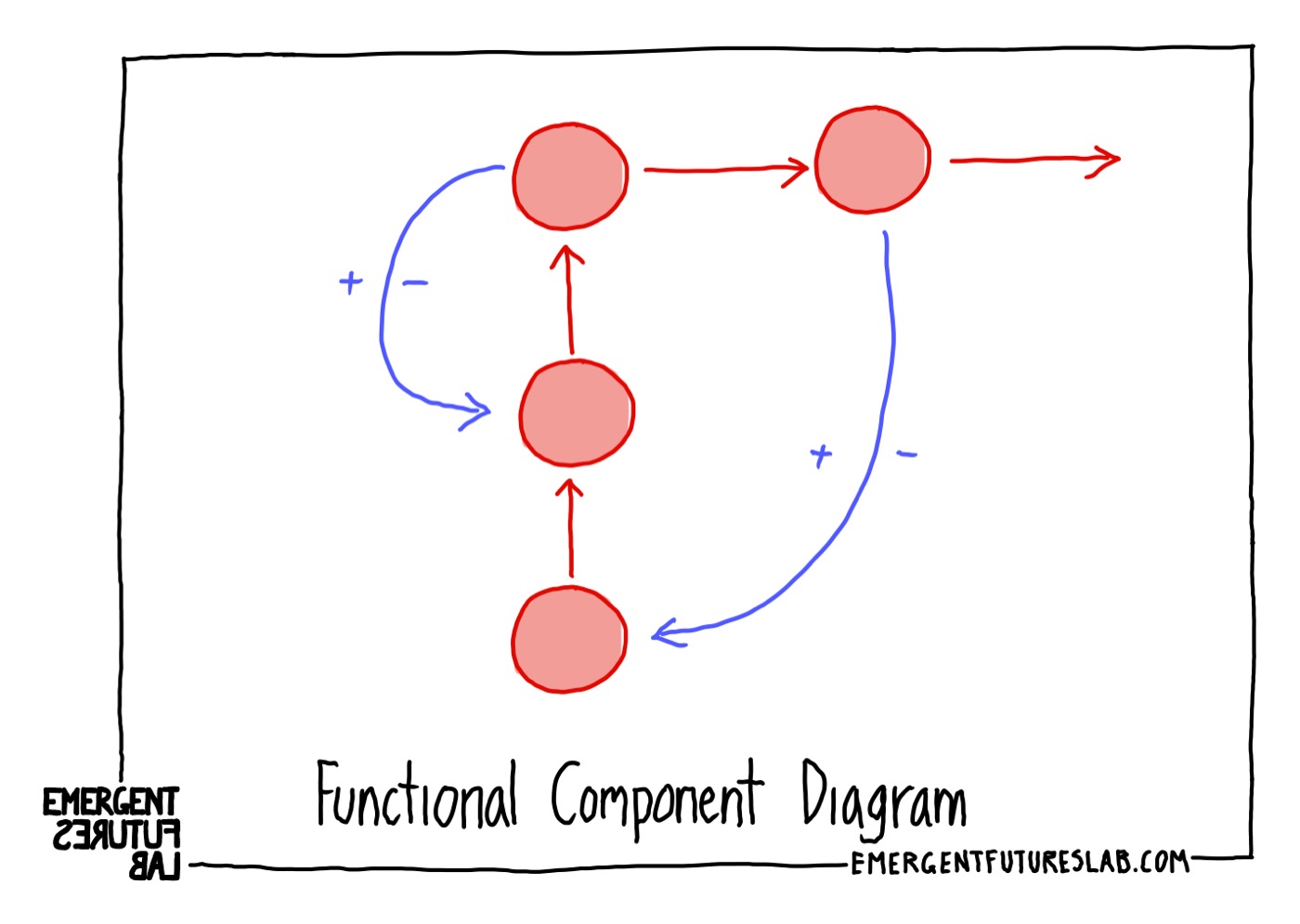

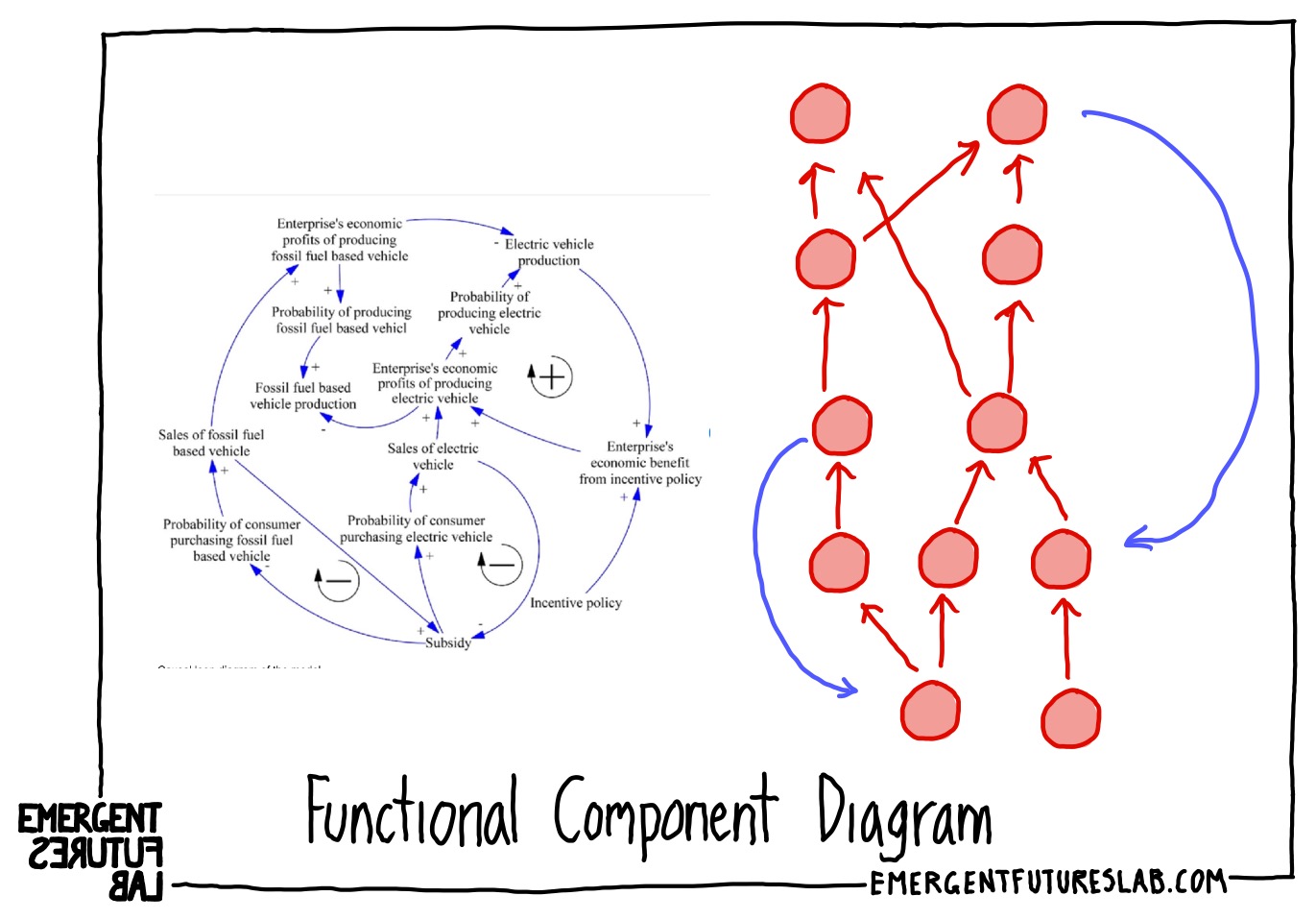

This logic of “how things work” understands outcomes as being the causal end product of many sequentially arranged components that each have a singular inherent function and are combined with feedback loops. We could diagram this at its simplest this way:

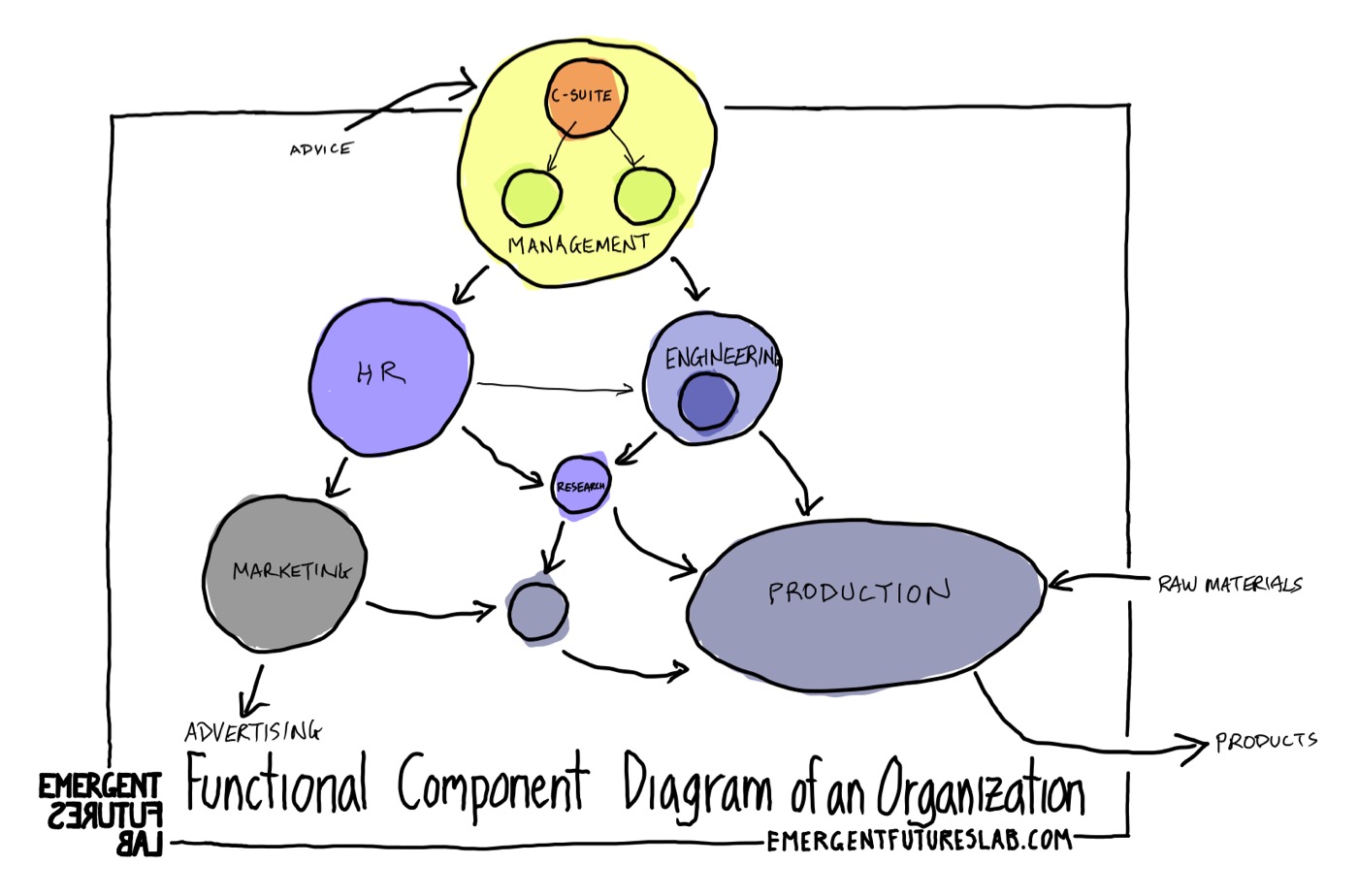

Culturally, we have applied this logic very broadly. We find it used to understand businesses and organizations: A business is a bounded system composed of various discrete functional components (e.g. departments) that work together in a sequential manner to produce an outcome:

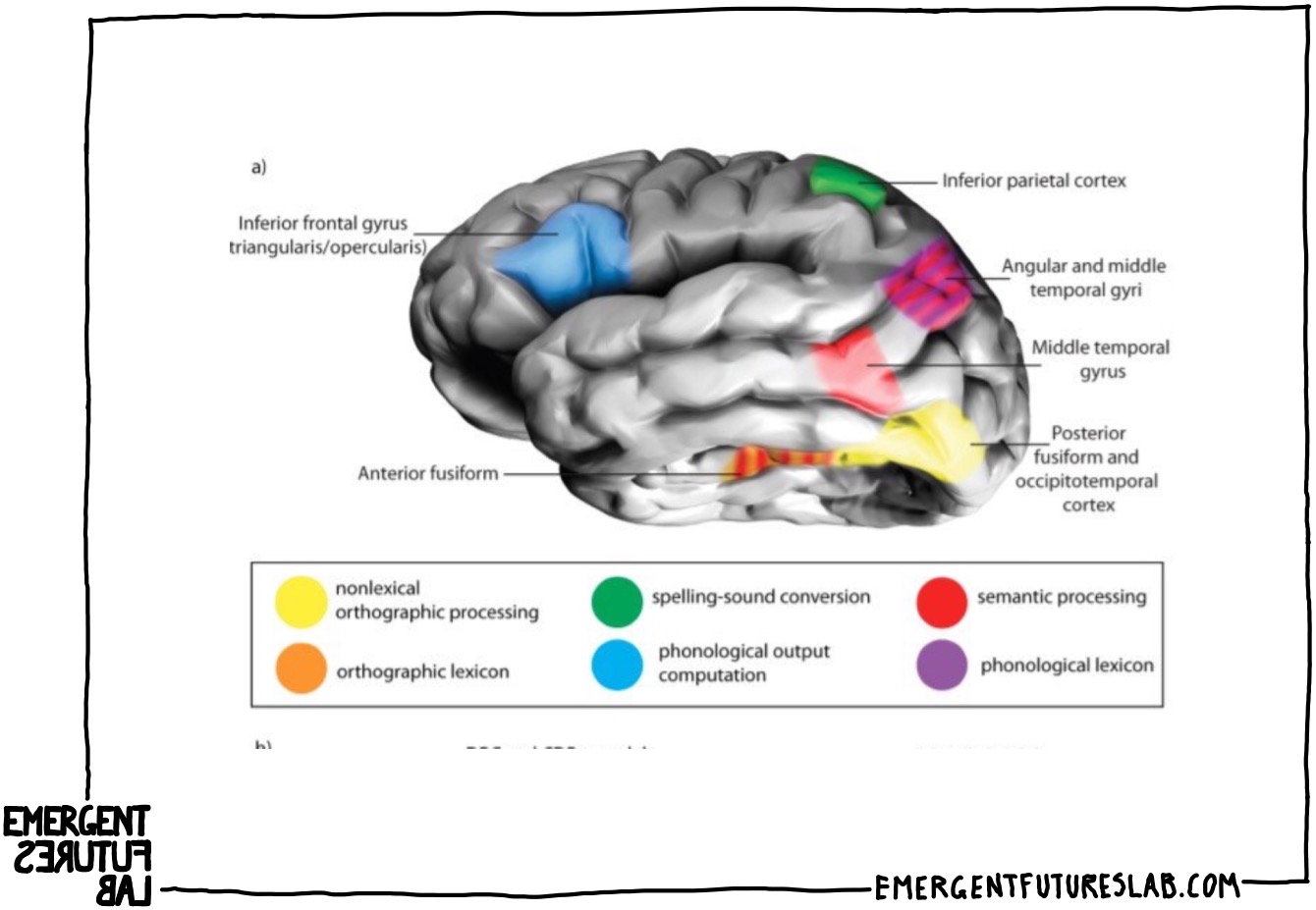

We have applied it to understanding living beings and brains. We understand ourselves to be composed of many discrete functional units: hands for grasping, eyes for seeing, hearts for pumping, stomach for digesting, etc.

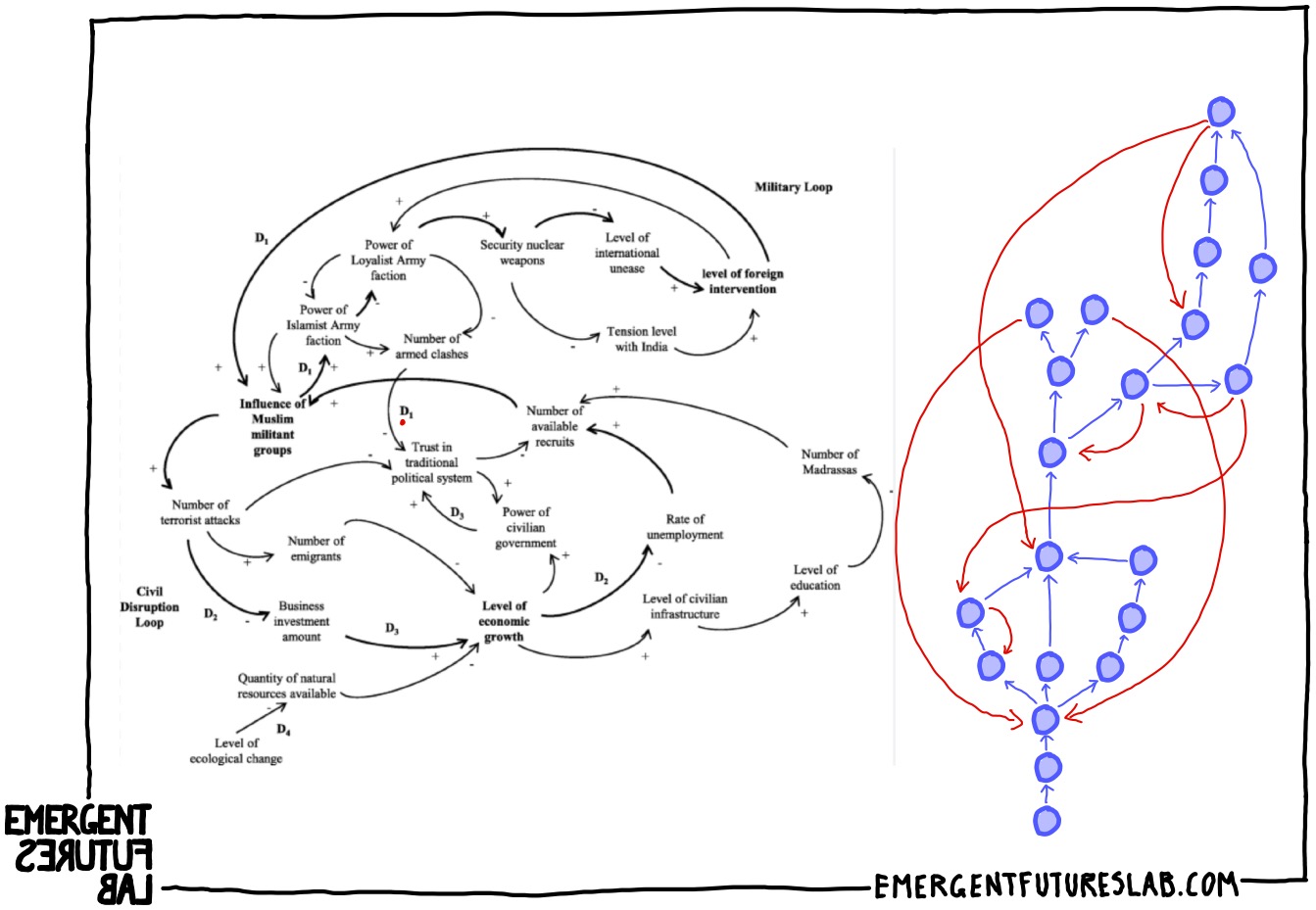

And we have applied it to understanding large social systems:

Now, this might be hard to see. After all, when we look at the above causal loop diagram of Systems Dynamics, it looks nothing like our exemplary functional diagram. But this is only because Systems Dynamics employs a drawing style that emphasizes the circularity of feedback loops. But this is just a drawing convention. If we use a more linear convention, this is what we would see - how it is in fact fully congruent with our Functional Component Diagram:

And this is equally true of the far more complicated causal loop diagram from last week’s newsletter:

From Org Charts, to Biology Diagrams, to Systems Dynamics, these models all surprisingly share three key attributes:

The question we want to answer today is:

Is this model realistic in ways that could be useful in complex circumstances? And to spoil the fun, no – in all the examples, other than motors, these systemic contexts – whether they are brains, bodies, businesses, or bustling cities do not operate via clear functional components working in linear causal chains modulated via feedback.

Now we have already extensively focused on the problems of confusing such complex adaptive systems with conditions in which something like linear causality may apply in very limited and highly circumscribed circumstances (see discussions of emergence, non-linearity, system causality, and Volume 195). And because we have already spent so much time digging into this set of issues, we will focus on what we feel is the most exemplary and overlooked problem with systems approaches: “the illusion of functional components”.

Before arguing against discrete functional components, let’s start with the argument that is made for the existence of discrete functional components: if we can purchase a product from an organization, then that organization must have a process by which to make it. And if we analyze any product we will see that it is composed of very distinct parts (advertising, packaging, testing, fabrication, shipping, development etc) – the same department cannot be doing all of this thus there must be the right series of sequenced departments (functional components) to produce this outcome. And this would also be equally true of something like human speech: there must be some set of connected functional components that are sequentially dedicated to the production of this outcome.

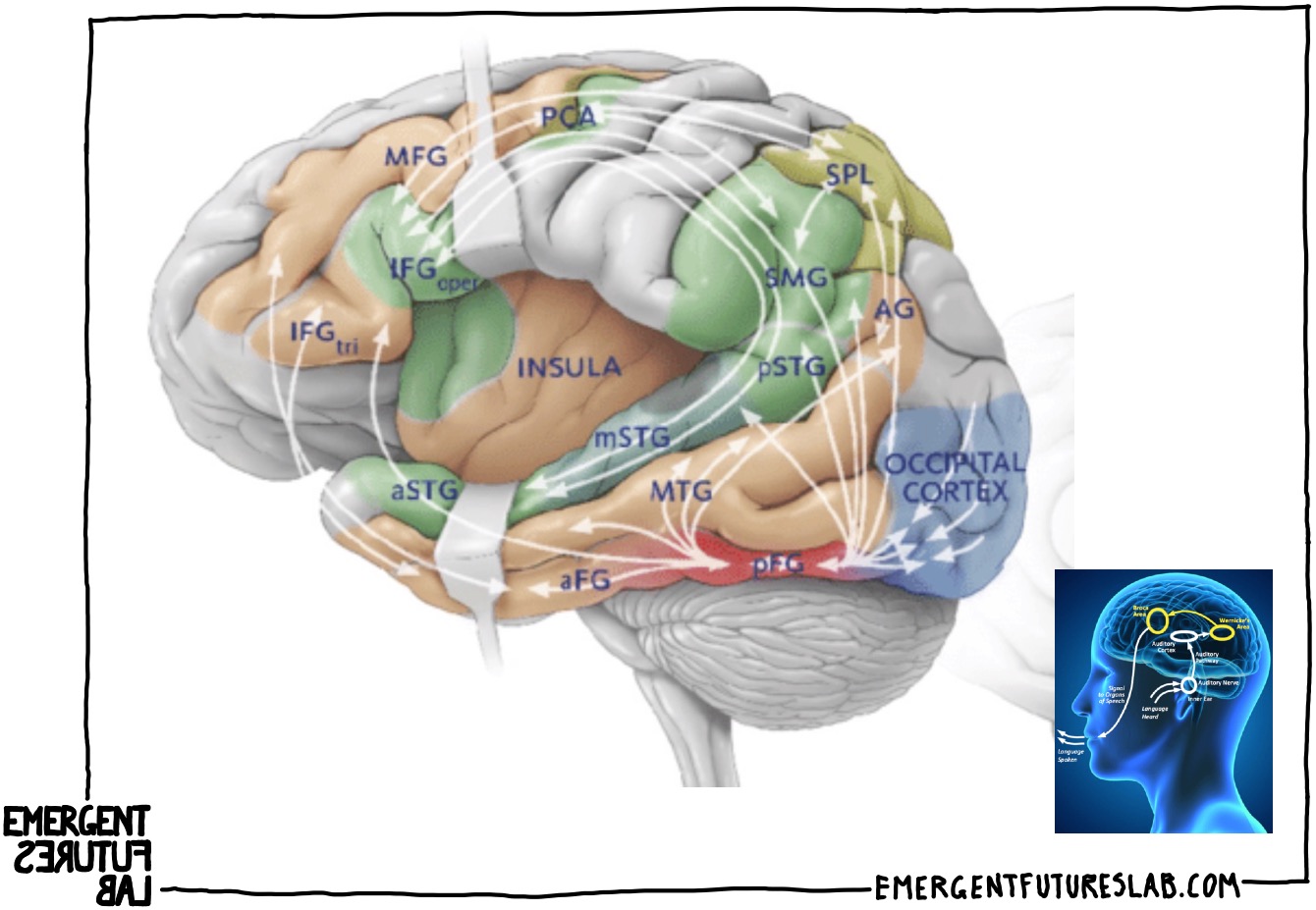

Let’s dig into the example of human speech, for it is so counterintuitive and simply utterly fascinating. For the longest time, it was assumed that there is a dedicated region or set of regions that control speech – the Broca and Wernicke’s areas. Gradually, the regions that participate in speech have expanded to contain a number of discrete functional modules:

This expansion was based on countless independent brain imaging research projects in which test subjects were asked to speak while in a brain imaging machine. And when all of these countless subjects spoke, the same areas of the brain would light up on the imaging machine. And from this, we can diagram the system. We should be able to see the clear, similar logic to these Functional Component Diagrams:

This singular function modular approach was the accepted understanding of how brains worked until the early twenty-first century. It was then that brain researcher Michael Anderson and his team began to ask the question: what happens if we overlay all of the location-based research, not just that associated with speech, but all of it? And by all of it, they meant every brain location study for touch, math, reasoning, smell, visual recognition, memory, etc., etc.

Now, if our brain had discreet functional units or modules, then we should see very little overlap between the areas each of these studies would pick out. But the research showed something very different:

Very different activities co-opt the same areas of the brain, but as part of very different temporary assemblages. There is no dedicated module or area or unit in the brain dedicated to any one task. Put simply, there are no modules in the brain dedicated to speech, for example. Rather, temporary assemblages form and shift as activities shift. Think about how astonishing this is and how radically counterintuitive it is to a culture steeped in a reductionism of functional essences.

One thing that is immediately interesting is that this is how the organizational theorist, Robert Cooper, described organizations. He argued that to conceptualize “generic organizations require that we relax the requirements for specific, locatable things that have specific, functional roles. Instead, [we should] think of organizations as loose and active assemblages of organizing – not static structures but dynamic acts that are always on the move”. (We explored this concept drawing on the work of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in more detail in Volume 162).

Now, one could argue that even if this dynamic shifting assemblage approach is correct, we would still be correct to diagram how speech functions exactly as we did previously – it's just that some of these areas also have other functions. But that would be to miss critical things that make this Functional Component Approach – and by extension, Systems Dynamics a misguided solution. With a singular functional component approach:

To really grasp how radical and transformative this dynamic co-optive assemblage approach is, we need to take things further.

Consider the game of football/soccer. It consists of a field activated by two goals on opposing ends, on which a ball is moved into or away from each goal via two teams of 11 players.

One way to define the players in this game would be as having fixed functional roles: the “Left Defender” has a fixed position (the left back area of their team's side of the field) and a fixed task (stop the other team’s players from getting the ball into the goal).

But this logic is not in any way essential or originary to the game. In fact, it is the strong reification and hardening of emergent properties of temporary assemblages into one status.

Now let’s shift to our dynamic assemblage perspective. Consider for a moment: the opposition has brought the ball near your goal – this situation creates a temporary functional assemblage:

And any player on your team near the ball, no matter what their formal position might be, takes on a temporary function: “defender”. The dynamic configuration produces new functions from old in a continuous dynamic. It speeds up players, slows down others, activates novel body parts, and bits of the field come into the status of a difference that makes a difference. Meaning, function, purpose – is in and of the intensities of the dynamic assemblage.

And as the ball is moved out of your end, the same players shift to become “offense”. The functional contribution being selected (or better said: created) always varies over time as a function of the specific dynamics of the configuration of the shifting assemblages.

To make the claim that there are fixed positions with fixed functions in soccer is to confuse the actual emergent pattern with a fictitious and ultimately non-existent underlying structure.

Another good example of this is grammar. Noam Chomsky famously argued back in the 1960s that, given the perceived nearly universal similarities in the basic logic of all human languages, we must all be born with something like a universal grammar module. The regularities we encounter in speaking – languaging do not require anything other than an intensively charged condition produced by a dynamic temporary assemblage…

Much of the apparent functionalist logic in the diagrams of Systems Dynamics are of this kind – it is the outcome of searching for idealized single-function units where there are simply none to be found.

It's not that there are no R&D departments, or Hands, or Subsidies, or Fascist Militias – of course there are. But none of these ever acts as a fixed functional unit with a pre-given causal logic. Take your hands, for example – what is their “function”? Well, they do a lot of grasping. So is this the function of the hand? What about when we put two fingers in our mouth and whistle? Or tap on piano keys? Or house fungi under our nails? Or help us add numbers, make rude gestures, or get cut off and left under a rock – what of all these very distinct functions? There is no fixed use to any thing – nor is there any use outside of how they are taken up in multiple very dynamic, differing temporary agential assemblages. This is the liveliness of life in all of its dynamic, multiple, temporary, emergent, strangely looping becomings.

So, what might be more helpful to focus on than the neat circles and lines of the functional units and linear causes of Systems Dynamics?

That is a good question. And it is going to be the exploratory focus of another newsletter.

But not to leave this totally hanging, we would start with the creative enabling differential intensities produced by the emergent dynamics of the configuration of an assemblage.

Think more “total soccer” and less functional units….

Think more enabling and stabilizing configurations and their emergent propensities, and less causality

Have an astonishing week getting out and experimentally participating in lively new worldly assemblages.

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.