WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 195! Creativity Critiques Systems Thinking?...

Good Morning dynamic and unexpectedly changing synergies,

What’s Wrong With Systems?

One of the great joys of writing the newsletter every week has been to interact with so many of you and one thing we heard from many of you when we brought up what we considered “the second error in considering technology” (which was understanding assemblages and systems in general to be like subway systems) – was why exactly are we critical of System Thinking?

And we are critical of systems thinking – but it is not for what might seem like the most obvious answer (because it is wrong)...

This topic led to some great conversations about the problems with systems in our WorldMakers community, and from there it has evolved into what felt like an important topic to address as we ended our series on technologies. So this week we begin a two-volume series on “the problems with systems” – But before we dig in:

For us, as we mentioned last week, a special anniversary is coming up: on July 11th, we will publish our 200th Emerging Futures Newsletter! And because of this, to celebrate our two hundredth issue, we would like to publish some personal reflections from you, our readers, on what the newsletter has meant to you.

If you wish, please take a moment to email us a reflection – it could be in any format (a letter, a video recording, an audio file, a drawing, a photo). And it could be any length – short or long. For our 200th issue, we just want to focus on you and what you have done with it.

In writing this week's newsletter we have been referring to its topic informally as “Why Systems Thinking Sucks”. If taken literally and without context, it is a very unkind and reactionary claim. And in our media landscape, where many propensities are towards polemic avalanches, it would be a mistake to add in any way to all of this.

That said, for us, when we encounter Systems Thinking – it is complicated – and we would say that “Systems Thinking Sucks” is an accurate claim, but only in an ironic and ultimately playful manner.

The thing is, as many in the change making community have come to realize, everything is interwoven – every thing is, you might say: complex and systematic. So we do, generally speaking, require “systems thinking” approaches. But a big part of the problem is that systems approaches have not been part of our intellectual history for long, and systems are profoundly and emergently messy. It is more accurate and fair to say that all of our current approaches to systems suck. They all fall victim to generalizing far too far from their initial scope of applicability – or repeating the patterns of essentialist approaches in the couture of an avant garde systemic fashion.

But, this claim lets nothing off the hook. While things might suck in general – each thing must ultimately suck in its own unique way.

So what of this is ironic? The irony is not that it is not just that System Thinking alone sucks – it is that even if Systems Thinking was wrong – it would not mean that we could discount its utility. In complex situations, we cannot say in advance what the impact of something will be. What could be more wonderfully ironic from a systems perspective than that a factually wrong approach might have a positive impact? And that a factually correct approach might have a disastrous impact. This is the, perhaps bitter for us, but joyful to us, irony of the situation. Effects and truth claims are very different things.

This is very different from saying “even a broken watch is correct twice a day” – for the effect of a broken watch is that it is never useful as a watch (never mind that it is theoretically correct twice a day). That effects are distinct from factuality is closer to the powerful effects of so-called “placebos.” Ultimately, there are only effects. To paraphrase William James: everything that has an effect is equally real. And all effects are highly contextually co-created (we are back to worlds-in-the-making, assemblages, and strange loops).

Thus, in one context something might work – that is to say, have a desired effect – but in another very similar context, almost identical context, it could be a very different story. And that effect is never the end of the story:

There’s the famous parable of the two farmers. Each has a son, and it is harvest time. One son has just been kicked by a horse while harvesting.

“It is really tragic that your son has broken his leg, right at harvest time – how will you be able to collect the harvest in time before winter? …”

“We shall see…” is all the other farmer says. “We shall see…”

Shortly after, the local government declares war and calls up all the able-bodied young men.

“I have lost my son to this foolish war and don’t know if he will ever return. How shall I continue to farm? You are so lucky that your son broke his leg…”

“We shall see…”

While Systems Thinking can be thought of as a useful catchall term for all the myriad of approaches to thinking about systems, it also names a very particular approach to systems. And it is this particular popular and widespread approach that we wish to critically explore in the next two newsletters.

Systems Thinking, or as it is more accurately known, Systems Dynamics, which was developed in the mid-twentieth century, is a way of understanding, modeling, and intervening in complex dynamic events. It uses the powerful abstractions of Stocks, Flows, Positive and Negative Feedback Loops, and Leverage Points – with the basic assumption that if you can model a dynamic system accurately, then you can develop effective ways to intervene in the system to shift it in desired directions. Major figures in its development include Jay Forrester, Donella Meadows, and Peter Senge (we have discussed Donella Meadows' work on Leverage Points in a previous newsletters: first in Vol 53, and her approach to systems: Vol 105).

The power of the Systems Dynamics approach is that it lets us very quickly visualize systems as multiple cycles held in dynamic equilibrium.

Here is a simple example: Coffee Drinking.

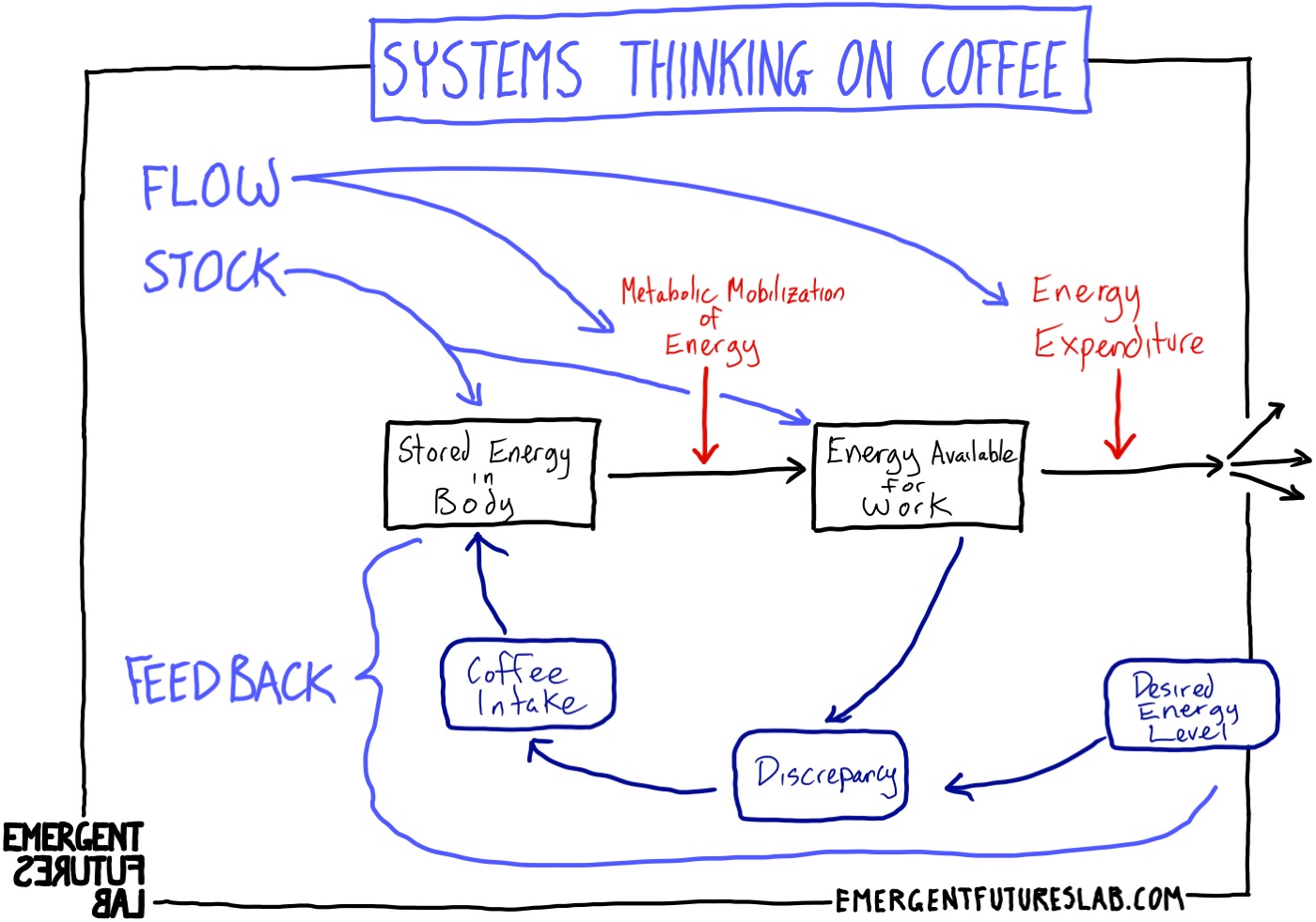

This is something that I do quite a bit of – as I imagine many of you also do – and so it can act as a familiar test case. Donella Meadows models this practice as a form of stabilizing feedback:

“If you’re a coffee drinker, when your energy level runs low, you may grab a cup of hot black stuff to perk you up again. You, as a coffee drinker, hold in your mind a desired stock level (energy for work). The purpose of this caffeine-delivery system is to keep your actual stock level near or at your desired level… It is the gap, the discrepancy, between your actual and desired levels of energy for work that drives your decision to adjust your daily caffeine intake.”

And this is diagramed as a series of connected stocks, flows, and feedback loops:

Now, while both this Systems Dynamics approach to explaining why one drinks coffee, and its subsequent modelling is deeply flawed in how utterly devoid it is of lived complexity and larger eco-social processes, it is highly seductive in its simplification/abstraction. It does make coffee drinking understandable as a dynamic process of seeking energy equilibrium by conflating an aspect/perspective of an open system with the vast contextually changing dynamic, open, processual “system” (this is partially why the concept of an assemblage is far more effective – but that is for next week).

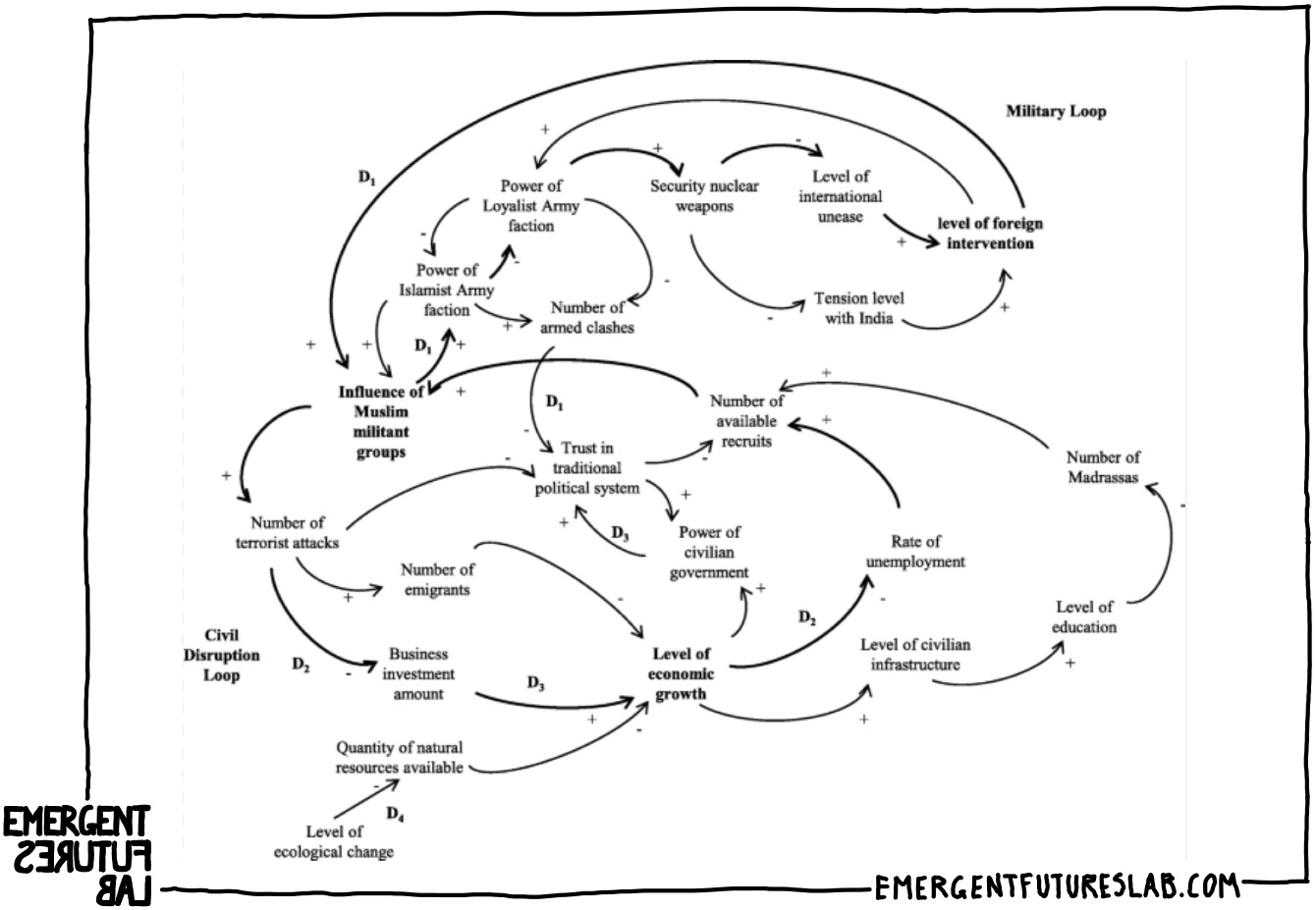

It is the seductiveness of this demonstrable process dynamics and the subsequent illusion of control that has helped the widespread adoption of this approach. Where coffee drinking is a fun test case, most System Dynamics work takes on much more consequential subjects. Here is an exemplary consequential application of this approach: “Using systems thinking to design actionable futures: a nuclear weapons example” by Leon D. Young from the European Journal of Futures Research. In a nutshell, this use of System Dynamics claims to have uncovered effective ways to de-escalate the Nuclear Arms race in Pakistan. Here is what Young claims Systems Thinking will allow us to do in general:

“This paper contends that the use of evidence-based methods allows foresight (futures thinking) work to be immediately operational and useful. Using a case study of nuclear weapon security within Pakistan, this paper explores the structured use of systems thinking, scenario development, and options analysis to develop plausible, feasible and actionable strategic policy options. The case study demonstrates that it is possible to develop quantifiable options derived out of traditional foresight methods. This paper argues that useful foresight needs to be tangible and provide feasible options.”

The critical claim is that one can understand, predict the futures of, and thus accurately intervene in a complex and highly contested system.

The approach is grounded in a four-step process of determining:

The whole process pivots on both the assumption that we can ascertain what will probably happen and that this can be modeled effectively. This is how Young describes the “What is Probable” step:

“This step draws from the systems thinking literature to model and simulate the environment. The aim of this step is to understand the points in the environment that can be influenced – the levers of change. This will be achieved, in this case, through the use of stock and flow models.”

And here is the diagram that is the outcome of this step in the Pakistan nuclear context:

There is something profoundly good about the hope that underpins this approach – the sense that we can have agency and improve things.

Young concludes in this exact spirit:

“Being able to generate future scenarios has always been a useful exercise; however, it appeared to lack a clear link with action. This demonstrated method allows for plausible future scenarios to be generated, analysed and used as a strong foundation to generate feasible strategic options. Where this method differs is the strong emphasis on developing a logical evidence chain that clearly links environment with option and preference. This then enables the analyst to confidently present their recommendation or amend the work should circumstances in the environment change dramatically.

The key advantage to this four-step process is the logical development of a chain of evidence. The key disadvantage is that this process requires more tools or methods, then would normally be expected from a foresight practitioner. That said, these methods are relatively well known and it is strongly recommended that foresight practitioners develop their systems thinking and understanding of systems dynamics.” (emphasis added).

The problem is the belief that this kind of mapping will lead to understanding and predicting outcomes on the mistaken assumption of how to understand “all things being equal”. If “all things being equal” is understood as radical unpredictability is rare, then we (and Systems Thinkers) are in for many a surprise. Now, it is not that mapping is never worth engaging with – this mapping does not and cannot do any more than help us begin to attune to the most general dynamics of a situation. And this is often good enough. The main failure in the causal application of this approach is that this is simply not how complex systems work.

Complex systems, to start with, are open and adaptive. That is to say, they are qualitatively changing in active response to what is happening – hence the term Adaptive (as in Complex Adaptive Systems). When something happens, the various other agents co-opt and transform effects in new and unexpected ways. Then they are doing this in an open, radically contingent manner, which is to say we cannot predict with any accuracy what will happen, even in the near term.

The final aspect of all of this emergence (which is what the use of the term “complex” is meant to denote in this context). Emergent systems are complex because one plus one is not two but something entirely different, and this difference is one that cannot be traced back to any component parts. And this traceability is precisely what the logic of leverage points assumes and ultimately why the Systems Dynamics mapping technique is deployed.

But the logic of emergence does not end there in its expression of a “bottom-up” logic. The emergent qualitative difference then exerts a “downward” or systems causality to transform the parts. None of this can be represented by a static diagram to begin with – nor is this something that one can “amend” should the circumstances change.

The cyclical, globally transforming nature of emergence redraws the diagram as it follows both the emergence of new agents and relations.

What System Dynamics does not consider is that fundamental to Complex Adaptive Systems is that in this condition of open adaptivity – when “everything is being equal” – new agents emerge, old ones transform (often qualitatively), and also disappear. And that the actual effects of all of this are untraceable back to any one aspect (and are thus non-knowable in advance).

This is the norm – the “all things being equal” of our reality. Despite any promise of developing a “logical chain of evidence” to plan for and execute from a distance towards a knowable in advance set of probable outcomes, the emergent, as yet non-existent and thus non-knowable radical possibilities are always ultimately outside of prediction. The illusion is that we can “effectively anticipate the unknown “unknowables” in planning – and we cannot.

That sense of hope is important but it is transmuted into an approach that assumes we can gain a full abstract understanding of a large-scale open and highly dynamic real world scenario and that once we accurately map it we can plan an effective set of interventions that will with a fair deal of statistical certainty have a net positive outcome.

Let's take a moment to consider how to understand the future and probabilities. The future, the new, is non-existent. The radically new is a “non-existent non-knowable”. It is not an “unknown unknownable”. Nor is it to be found in the explication of present probabilities by the logical chain of evidence developed by a Systems Dynamics process.

The known, the knowable, and the imaginable are all activities that extend the present into the future along lines that can be postulated by probabilities and possibilities. But there is a clear limit to knowable futures, and that is in the realm of probabilities. And the logic of probabilities can never exhaust the always-present contingencies of what might emerge. But more importantly, the making of the future does not have a default setting where “more of the same” requires any less a creative effort than something radically novel. The future is not a vacuum where the same will continue until interrupted. It is always in-the-creative-making.

Ultimately, neither the logic of probabilities nor the speculative techniques of the imagination can assist us in relation to working with the radically contingent aspects of the creative processes of the emergence of the qualitatively new. Why? Both the calculus of probabilities and techniques of speculation are extensions of the present into the future as if it were not always in the making.

One part of the issue in dealing with the non-knowable is that we think, plan, and imagine in terms of “the possible”. This becomes really clear when we think about how awkward our language becomes in trying to describe the "non-existent non-knowables” – we don’t even have a good vocabulary for the non-existent! While we have so many great terms like the probable, possible, and potential to deal with the new but knowable…

We need to remember our farmer – “we shall see…”

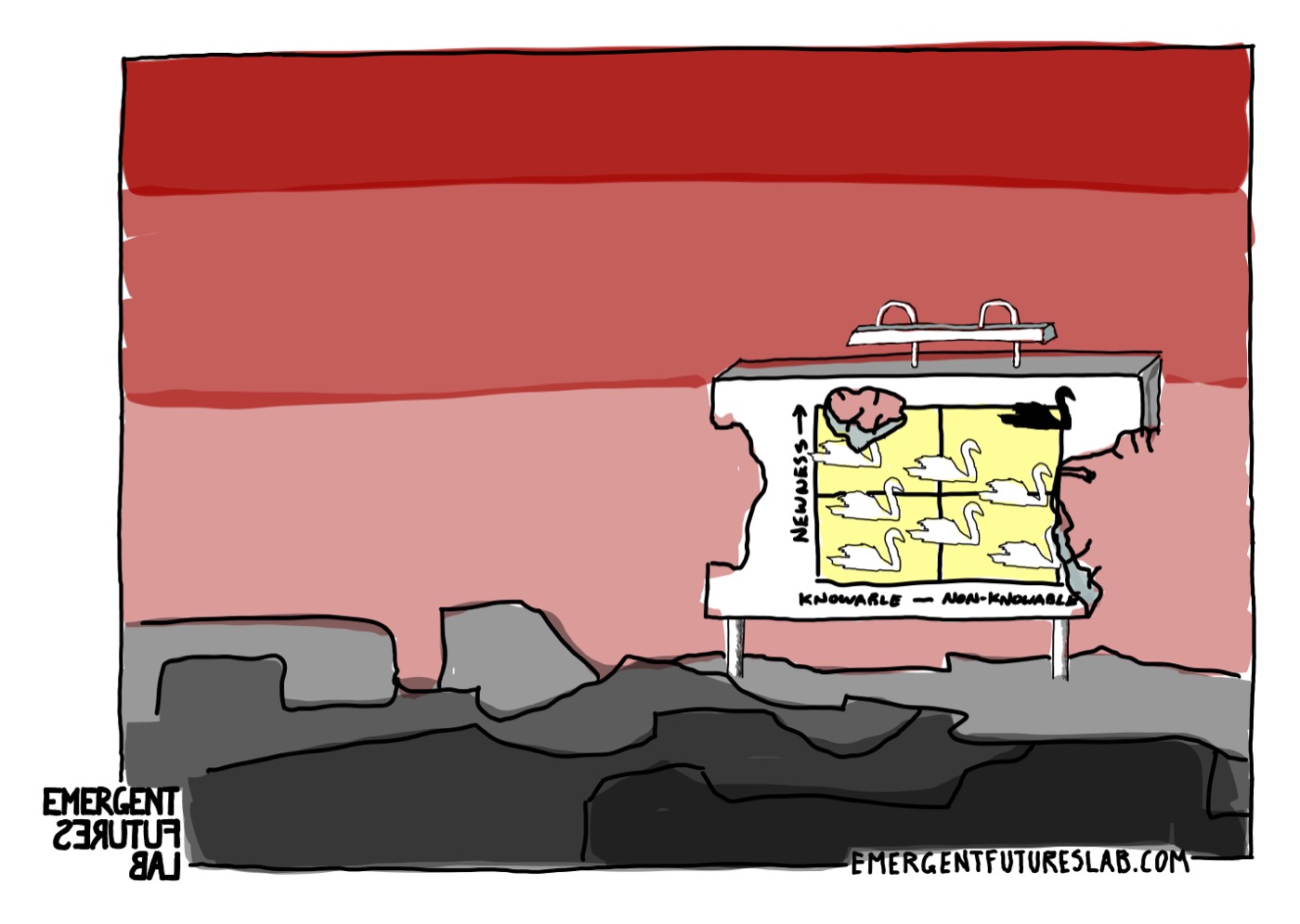

One approach to all of this is to categorize the radically new as something rare – a Black Swan in a mostly White Swan world.

So, how should we, the inhabitants of a seemingly mostly White Swan world, deal with Black Swan events according to Systems Dynamics?

The recommended practice is that:

Which can seem like sound, pragmatic, and rational advice. But is such conservative advice adequate to come to terms with the radically contingent and utterly excessive nature of our non-knowable future reality? It is a bit like getting school children to practice for a nuclear attack by getting under their desks…

Being humble, yes. Being anti-fragile is also good, but we should not consider this as a relevant response to radical contingency.

Why? We would argue that there is no neat division between black and white swans. Perhaps all swans are black…

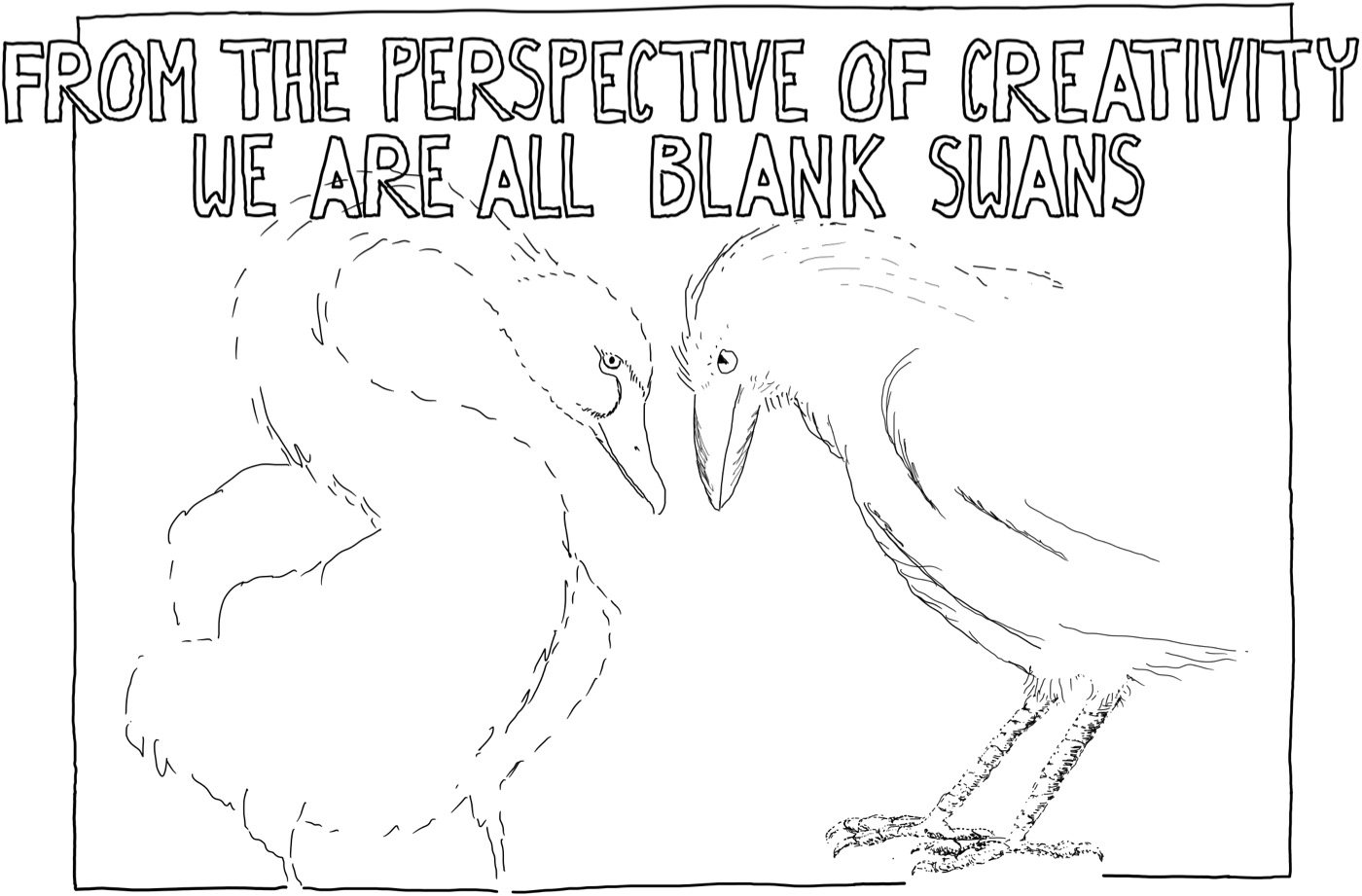

Here is the problem: the categories of the “probable” and the “unlikely” are false categories, as reality is radically contingent. We cannot say in advance with any certainty what is actually unlikely. Then all swans are black. Or to be a bit more accurate, all white swans are also black swans. Elie Ayache, who we draw upon along with the work of Jon Roffe, calls all swans “Blank Swans” in the wonderfully provocative book Blank Swans: The End of Probability.

We tend to use a spatial logic for forms of change, often with neat quadrant diagrams. The White Swans will always get three quadrants, and those shocks to the system (the black swans) that come from the outside to disrupt everything, they will get some small corner of one quadrant. But the radically new is not something spatializable – it is not lurking like a black swan just out of sight around some corner. Rather, it is nowhere or better: everywhere: it is the “blank swan” that could be either black or white depending on anything...

We have misunderstood our history – imagining always that “only now” is everything uncertain – that only now we live in a “whitewater” of VUCA world (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous). We have made it all White Swans…

We need a history that shows how the radically contingent and different is already immanent in everything. That everything is of a history but is also untimely. The new in all of its forms “haunts” everything and every moment of the present. Our challenge is that all swans are both white, black, and also blank.

The challenge to Systems Dynamics and all probabilistic modeling is that the future is not “just” the non-knowable as the correctly surmise but is also not something other than this.

Because of this, it can seem like we are totally working in the dark (which is true and not-true).

It might be more useful to consider that we are working at the emergent edge, we are always at a “blank edge” – a true edge where there is nothing beyond. And that the new, whether mundane (white swans) or radically qualitatively novel futures (black swans) are made as a “path is made in the walking” – with great creative effort either way. We are, despite what it may seem like, always taking a step into the co-emergent non-existent…

And this is nothing new – all life is lived this way – ask any mother giving birth – it is always a path made in walking or pushing – or waddling at the edge…

Well, that is it for this week – we are currently co-emerging towards our next newsletter, which we hope to focus on how to make sense of radical contingencies beyond the limits of Systems Thinking…

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.