WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 207! A Thousand Creativities...

Good morning multiplicities forming imperceptible consistencies,

This week we are back with you: those who are also “several” and doing the creative work of the “making of the unrecognizable” – experimenting as Deleuze and Guattari suggest “to reach, not the point where one no longer says I, but the point where it is no longer of any importance whether one says I.”

There is something so refreshing about this phrase in relation to questions of creativity – to be at the point where it is no longer important whether one says I…

“A Thousand Plateaus… was our most ambitious, most immoderate and worst received work” (Gilles Deleuze 1986)

Yes, we are back with D & G and the event of lightly surveying the book, A Thousand Plateaus. Last week, we began this series by introducing some relevant contextual information on the work of Deleuze, Guattari and their collaborations. Our hope in this series is to both bring this important book on creativity to your attention in an interesting and catalyzing manner, and to offer a series of concepts, tools, and practices that come from this work that we have found to be really relevant and helpful to our engagement with creative practices.

To this end, we recommend a quick review of five key concepts (from the perspective of creativity) from last week's newsletter:

Representational thinking is a thinking that, by definition, turns the new into the given. We see, recognize, and know in one act – and if there was something totally new in the midst of all of this, how would I even begin to recognize it?

“Something in the world forces us to think. This something is an object not of recognition but of a fundamental encounter” (Deleuze in Difference and Repetition). We are forced to think by the shock of an encounter. Here, there is no correct answer, no understanding, no words, no concepts – nothing we can imagine – unless we turn the new back into the known. Thinking – creative thinking – is an involuntary adventure that begins at the limits of our re-presentational ideational thinking. In the shock of an encounter, beyond your knowing, your ways of sensing are pushed in new directions…

We hope that some of you will now have this book in hand – or managed to get your cat to let you have it back...

Creativity is all about going slow to go fast. So, let’s go slow: before even cracking the book open, let’s pause and consider the cover and the very short and enigmatic title:

Mille Plateaux

or

A Thousand Plateaus…

What of it?

Where can this take us?

The indefinite article: a…

A Storm, A Hurricane, A Riot, A Love…

D & G seem to love the indefinites, the third person plurals: one, it, a:

“one seems to…”

“it is raining…”

“a thousand plateaus…”

It is a silent, an invisible “a” – we could just as effectively say: storm, hurricane, riot, love or “thousand plateaus" (as is done in the French)

The indefinite article here connotes a specific event –the event of a thousand plateaus. The indefinite article designates it as a specific thing that is of a general type – but of which nothing determinate is said – or perhaps can be said. They do not write “THE Thousand Plateaus” – as if it were definitive. Nor do they write THIS Thousand Plateaus as if it were identifiable. Rather, it picks out something specific: “a thousand” – but it remains indefinite in terms of which exact ones are being picked out from a potentially larger set.

Still, the question remains: Which thousand? And of this we can, because of the indefinite article, expect nothing.

This is something unique. Philosophy books, in the Western-Asian tradition, tend to be descriptive – they take it as their task to describe truthfully and fully what really exists at a fundamental level. But Deleuze and Guattari already announced with this indefinite title that this book cannot and will not be a work of description – it will not tell us what “is”. It is already calling into question the totalizing descriptive goals of this tradition.

Additionally, philosophy, in this tradition, tends equally to be proscriptive – it moves smoothly from total claims of “what is” to exact claims of “what should be done” – of what we should do. But in the face of an indefinite – can this be the case here? No.

So what is left?

This leads to an important set of questions for how we approach creative practices: Why, from the perspective of creativity, don’t we want to say either “what is” or “what should be done?” And if we do not do this, what is left? Let us take this newsletter to explore this question: What could a book A Thousand…

Yes, there are a thousand somethings – plateaus (more on that later). Why a “thousand” say versus nine-hundred and eighty or two thousand? What tendency does this concept of a “thousand” possibly suggest?

The forty-second chapter of the Dao De Jing begins in a seemingly precise and austere manner of numbering:

Way-making (dao) engenders one,

One two,

Two three

And three, ten thousand things

This is a translation by Roger Ames and David Hall – who also offer a second reading,

“This might also be read:

Way-making (dao) gives rise to continuity,

continuity to difference,

difference to plurality

and plurality, to multiplicity.”

Ten thousand things – multiplicity

Here too is a conceptual number: ten thousand activating the space of a conceptual difference that cannot be reduced, summarized, or made to correspond to one thing, to one source. It is an active continuity of difference. A non-quantitative number – the many.

Ames and Hall, in a very helpful passage that gets at both the uniqueness of Daoism as a philosophy and what is perhaps necessary to a radical creativity, have this to say about multiplicity and the “ten thousand things” in Daoism:

“The Daoist… cosmology begins from the assumption that the endless stream of always novel yet still continuous situations we encounter are real, and hence, that there is ontological parity among the things and events that constitute our lives…

We might say that for the Daoist… "only becomings are." That is, the Daoist does not posit the existence of some permanent reality behind appearances, some unchanging substratum, some essential defining aspect behind the accidents of change. Rather, there is just the ceaseless and usually cadenced flow of experience.

In fact, the absence of the "One behind the many" metaphysics makes our uncritical use of the philosophic term "cosmology" to characterize Daoism, at least in the familiar classical Greek sense of this word, highly problematic. In early Greek philosophy, the term "kosmos" connotes a clustered range of meanings, including arche (originative, material, and efficient cause/ultimate undemonstrable principle), logos (underlying organizational principle), theoria (contemplation), nomos (law), theios (divinity), and nous (intelligibility). In combination, this cluster of terms conjures forth some notion of a single-ordered Divine universe governed by natural and moral laws that are ultimately intelligible to the human mind.

This "kosmos" terminology is culturally specific, and if applied uncritically to discuss the classical Daoist worldview, introduces a cultural reductionism that elides and thus conceals truly significant differences.

The Daoist understanding of "cosmos" as the "ten thousand things" means that, in effect, the Daoists have no concept of cosmos at all insofar as that notion entails a coherent, single-ordered world which is in any sense enclosed or defined.

The Daoists are, therefore, primarily "acosmotic" thinkers.

One implication of this distinction between a "cosmotic" and an "acosmotic" worldview is that, in the absence of some overarching arche or "beginning" as an explanation of the creative process, and under conditions which are thus "an-archic" in the philosophic sense of this term… difference is prior to identifiable similarities.

Here in these two books, we encounter two multiplicities: a “thousand” and “ten thousand” – two distinct radical perspectives on creativity meet: If creativity is everywhere and everywhere ongoing, there can be no unfounded beginning. And if there is no beginning, we are in a creative situation of difference – and the swarming buzzing multiplicitous becomings of differences differing prior to and in excess of identities.

“A Thousand” then is a cue, bringing us towards a multiplicity of lines of creative becoming that brings us into and through this book experimentally – co-constructively – where we will encounter the irreducibly qualitatively many in many ways: the several, the multiple lines of flight, the flows, assemblages, swarms, packs, hordes, etc.

This “thousand” is a non-numerable multiplicity, as they make clear, saying this already in the second paragraph of the book:

“It is a multiplicity [referring to the book] – but we do not know yet what the multiple entails when it is no longer attributed, that is, after it has been elevated to the status of the substantive… all we talk about are multiplicities…”

Key to all of this is to remember that both their collective work and Deleuze’s singular work has one pragmatic and experimental aim:

“...the aim is not to rediscover the eternal or the universal, but to find the conditions under which something new is produced (creativeness)” (Gilles Deleuze. Note, it is Deleuze who uses the English word “creativeness” here.)

And this brings us to the challenge: creation and creativity – if it really involves the wholly novel and wholly different, will always exceed the known, the knowable – and all forms of identity – all naming and numbering. Why? Identity operates via a logic of “this corresponds to that” – and this requires that we know what the “that” is before we begin – it has to assume something pre-given and unchanging – something fixed and specifiable that has always been there. But the logic of radical creativity leaves nothing outside of change and becoming. If we begin with something that we can identify and know, we have artificially put this outside of becoming: outside of “way-making.” Becoming without identity gives rise to continuity: A Thousand…

Paradoxically – well it could seem paradoxical after all this talk about irreducible multiplicities – but as we have seen by the above quote Deleuze and Guattari want to develop a single experimental constructivist process philosophy that can experimentally engage all creativity as one – from the big bang to Nina Simone – a multiplicity that can resonate towards all possible becomings: “creativeness – to find the conditions under which the new is produced.” And it is this project that makes this book so interesting and important to those engaged with creative processes. This book is an attempt to write a constructivist speculative philosophy engaging all worldly becomings – all creativities. This is one of the joyous qualities of this book: bacteria, wolves, lobster, rats, roads, mountains, fictions, quilts, children humming, wasps, faces, novellas, set theory, and sorcery…

But, this desire to engage with and experimentally stabilize the conditions under which all (the new) is produced as a “singular process” requires, at the very least, a brief comment:

West-Asia philosophy beginning in the 1700’s came to focus on the human and the problem of human access to reality (what is the human and what can we properly know?). Here, René Descartes, with his famous claim, “I think therefore I am,” is emblematic of this radical subjective anthropocentrism. He argues that we cannot be certain about anything about reality or ourselves beyond the reality that we think. But if all I can know is that “I think” – what is the world doing?

Of the world in itself, seemingly nothing can be said…

This human-centered and immaterial thinking-centered approach that begins with us dematerialized and divided from the world around us – and then strives to explain how we can have some limited access to reality has dominated Western philosophy, the cognitive sciences, and creativity studies up to the present moment. Creativity studies, for example, are profoundly human-centered, thinking-centric, subjective, and hyper-individualistic.

Deleuze and Guattari want to invent new problems beyond the recent West-Asian construction of the problem of how do we gain a true connection to the world outside the immaterial thinking self. They want to invent creative problems that begin with a focus on all life – organic and inorganic life – and its creative becoming: “to find the conditions under which something new is produced.”

For D and G, an all-encompassing creative reality means we need to experimentally consider the nature of all reality to be perspectival. Once every thing is active and every action relationally shifts things, then there can not be a view from nowhere. We are always partial – in the thick of things. That, in an ongoing co-creative reality, there are no “things in themselves” and therefore no access to “things in themselves” does not mean the human is forever outside of the world into a radically solitary and uncertain prison of radical subjectivity. Rather, any knowing (really sensing) is connected to an ongoing co-creative entangled activity. An activity that is a concerned, embedded, and extended doing (really co-creating). And in this, all action is emergent from the middle – and this is always already collective. For D and G to be able to experiment in this manner, we need to invent new problems, practices, and tools that can help us cross from the geological to the biological, from the chemical to the social, from the social to the symbolic… How else could we experimentally ask the question “what radically new possibilities can any life become?”

And then we are back to the myriad, the thousand, and the ten thousand…

So what of this last word in the title?

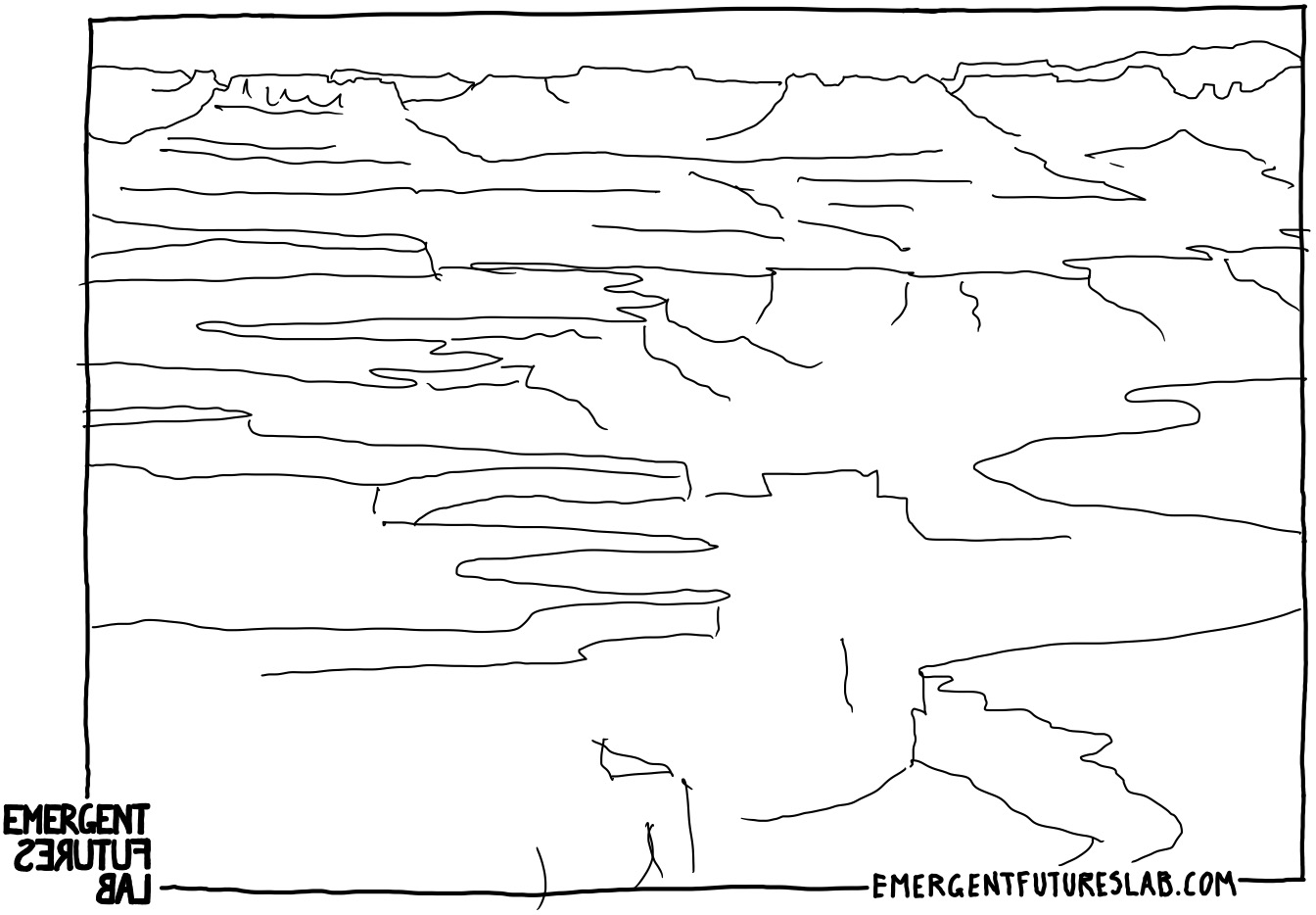

Plateaus?

Here, we give the floor to Deleuze from an interview in 1980 discussing the recent publication of A Thousand Plateaus, where he is answering a question about what they mean by plateaus:

“It's like a set of split rings. You can fit any one of them into any other. Each ring, or each plateau, ought to have its own climate, its own tone or timbre. It's a book of concepts… But there are various ways of looking at concepts. For ages people have used them to determine what something is (its essence). We, though, are interested in the circumstances in which things happen: in what situations, where, and when does a particular thing happen, how does it happen, and so on? A concept, as we see it, should express an event rather than an essence…

…In what situations does this happen, and why? Thus each ring or plateau has to map out a range of circumstances; that's why each has a date-an imaginary date-and an illustration, an image too. It's an illustrated book. What we're interested in, you see, are modes of individuation beyond those of things, persons, or subjects: the individuation, say, of a time of day, of a region, a climate, a river or a wind, of an event. And maybe it's a mistake to believe in the existence of things, persons, or subjects. The title A Thousand Plateaus refers to these individuations that don't individuate persons or things.”

A plateau is also a geological event. It is a raised plane. Neither a mountain nor a valley – but a limited raised field condition. It is a terrain without a high point – without a peak – nowhere one could say “we made it! We have arrived at the summit” – a plateau has no finality, no bottom or top – it is rather as they say elsewhere “a zone of intensity.” Plateaus make a patchwork of consistencies. Discreet territories at the edge of eroding into new forms. Becomings – creativities are acts of deteritorialization and reterritorialization.

An experimental geo-philosophy:

“Thinking takes place in the relationship of territory and the earth… we have seen that the earth constantly carries out a movement of deterritorialization on the spot, by which it goes beyond any territory: it is deterritorializing and deterritorialized… The earth is not one element among others but rather brings together all the elements within a single embrace while using one or another of them to deterritorialize territory.”

We have perhaps overstayed our experimental welcome with the cover. Let’s gently open this book (after all, we want it to last at least 20 years before it all falls apart). The English edition has a wonderful introduction by the translator and great philosopher, Brian Massumi. He notes some important complexities in translating certain words. It is worth a careful read.

But for now, we will skip over this and go straight to the first page.

If a radical creativity requires experiments that are neither descriptive nor prescriptive – but our habits of reading are – then how should we proceed with reading?

Here we should recall that thinking is not something that comes naturally to us:

“Something in the world forces us to think. This something is an object not of recognition but of a fundamental encounter”

And that's what emerges – thinking is a creative act. It is never a passive act of absorption – in an ever-creative reality, there is no still spot – no non-active spot – no action that does not have an effect – not even reading…

So what new art of creative reading do we need to co-create?

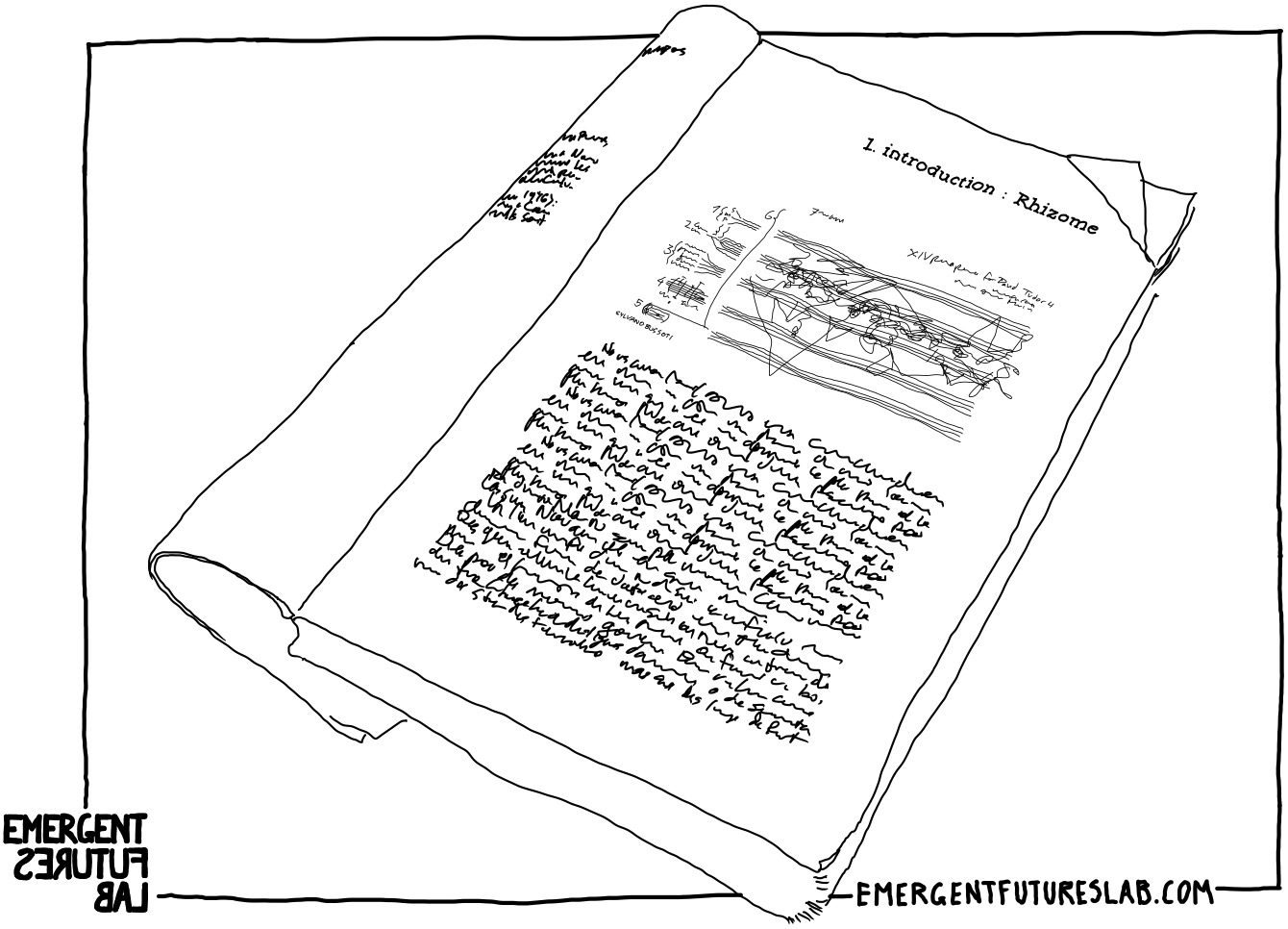

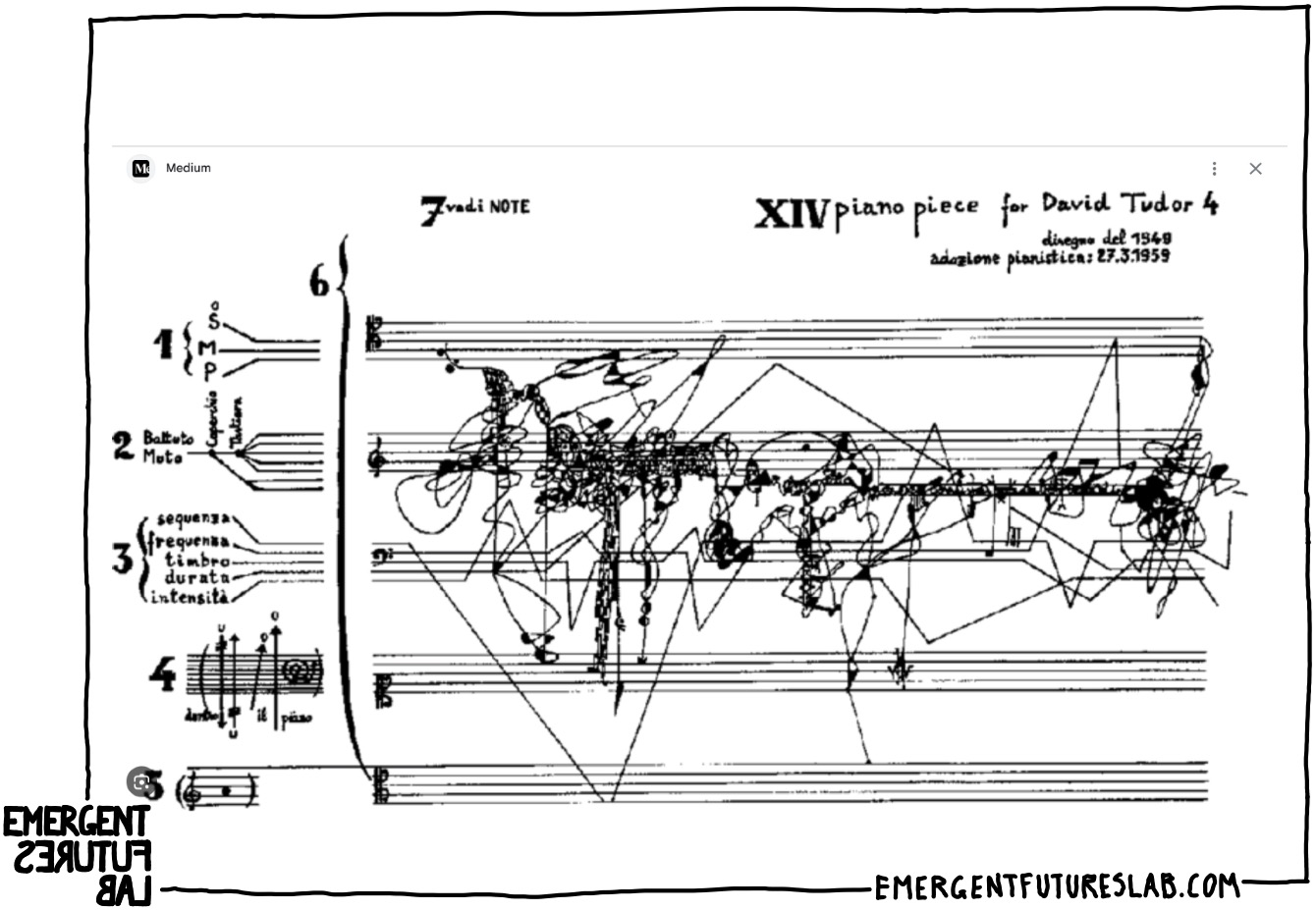

Now that we have opened the book to its first page, before any writing, we are confronted with a musical score:

It is a composition: Five Piano Pieces for David Tudor” by Sylvano Bussotti. And it is the first part of the fourth piece. Now, if one has a sense of classical European musical notation, this piece looks like spiders that fell into an ink pot have crawled across the page.

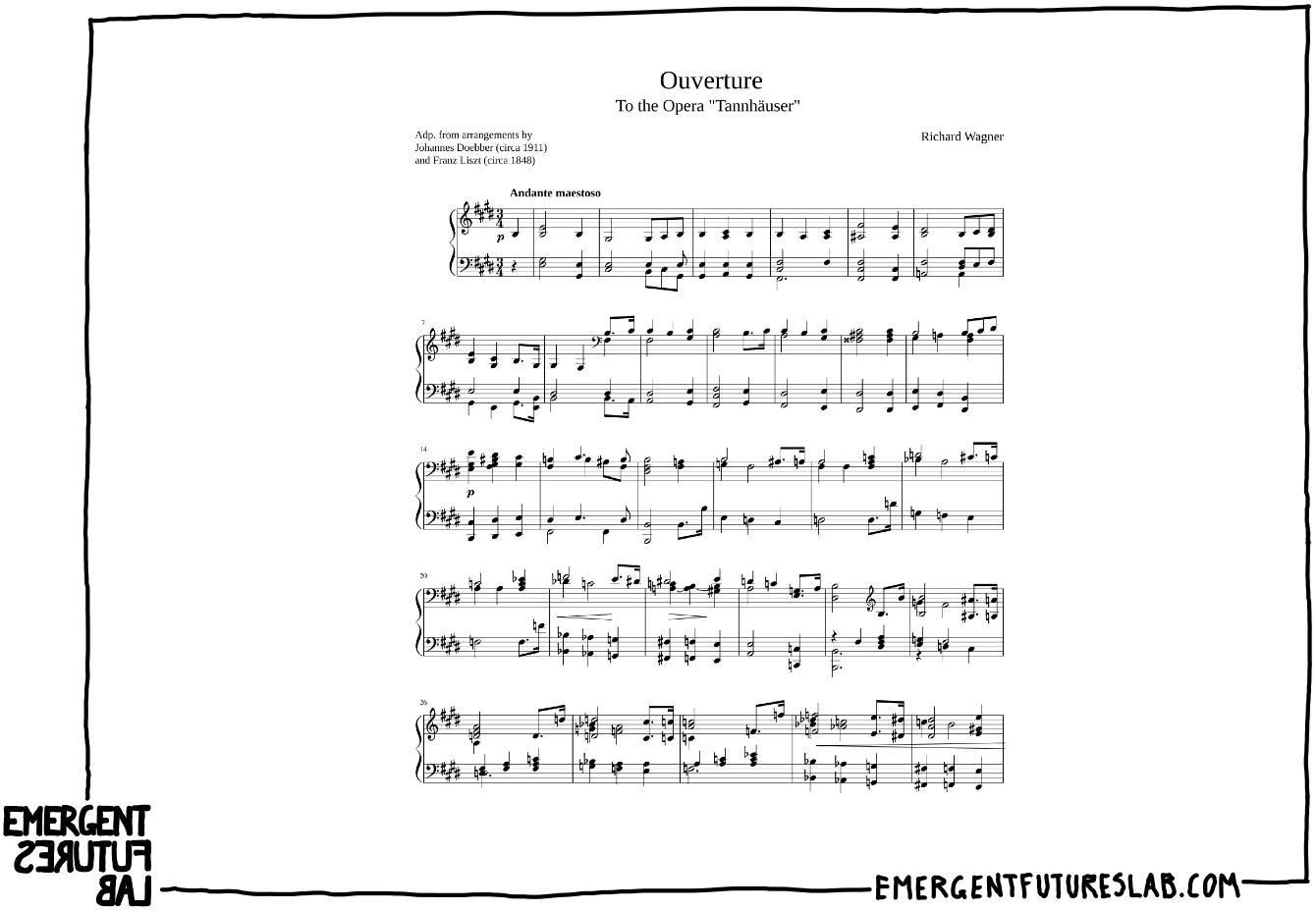

For comparison, here is another piece for solo piano that is notated in a more conventional manner:

Here, we can see each note and all of its qualities are exactly laid out – this score acts as a clear tracing or representation of what the composer intends. Of course, there is a space – a flexibility for interpretation. But we are in the realm of a pre-given entity where a limited range of variation is all that is accepted. The score acts as a fixed point, the unchanging anchor. It is both descriptive and proscriptive.

But what of “Five Piano Pieces for David Tudor”? Does it allow one to do anything? Not really – it is equally exact – we equally have every line drawn out. There are even lines for intensity, duration, and timbre. But what is missing is any imposition of instructions on how to activate these lines into sonic actions with a piano.

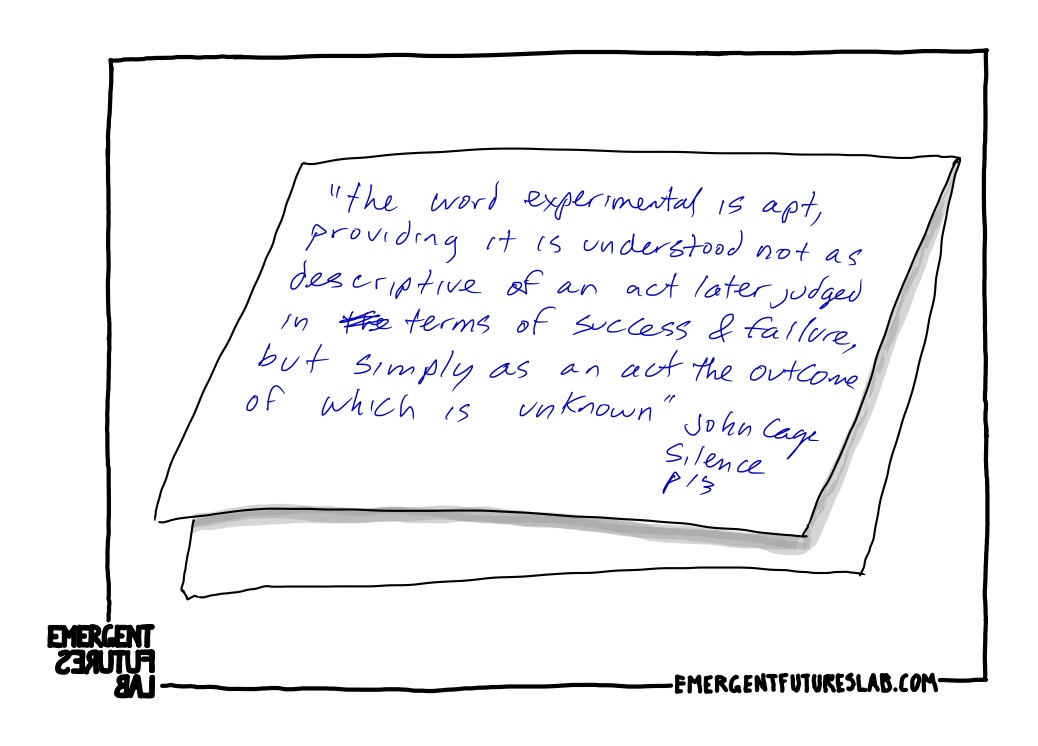

The title offers us an important clue: “for David Tudor”. Who is David Tudor? He was an important experimental musician and pianist who was famous for the careful creative effort he put into the experimental (in Cage’s sense, see above) realization of these indeterminate works.

Importantly, in advance of any actualization of this score, there is no determinate sound to this piece – even for the composer. The composer has produced a specific problem, and left open how it is activated and creatively actualized. Here we have what Deleuze calls a “problematics,” an invention of new problems – rather than a situation of imposed description and proscription.

This work calls for a sensing, joining, following, and co-creating. Over the week, Jason and Iain experimented with ways of actualizing it. Below is an early draft of Iain’s initial experiments to attune to the score:

Here is one of Iain’s Experimental realizations.

Jason went in a different and fascinating direction: here is a video of one of Jason’s experimental ecologies, and here is the full actualization.

And here is a video of Diego Petrella actualizing this work. He begins with a wonderful introduction to the piece and his experimental approach.

Now neither of us would ever claim that our actualizations are anything but amateur experiments of the simplest kind. But what matters is that they attune one as a reader to a new image of creative action that is called forth by the novel problematizations – plateaus that this book presents us with as terrains for rigorous experimental actualizations. Our readings, similar to our actualizations of Bussotti’s work, are works – actualizations in and of themselves.

So here is our thought: One way we have found to experiment with this book is to see that each plateau invents a novel problem in one of a number of general areas of concern (the creativity of inorganic life, collectives and creativity, self-creativities, etc.). One of these we term: New Approaches to Creative Action (in General).

Deleuze speaks of it in this manner:

[We need] a new image of thought - or rather, a liberation of thought from those images which imprison it: this is what I… sought to discover... [in] subsequent books up to and including the research undertaken with Guattari where we invoked a vegetal model of thought: the rhizome in opposition to the tree, a rhizome-thought instead of an arborescent thought”

This work can be found in three plateaus:

1. Introduction: Rhizome

12. 1227: Treatise on Nomadology – The War Machine

14. 1440: The Smooth and the Striated

We would like to propose that we read this for next week. Now this might be a lot to read for next week – but let's try. If there is only time for a bit, we would suggest sticking to the Rhizome – or finding a way to skip across all three – dipping in here and there (the table of contents is helpful in this).

Just remember – it is a creative dance: they are inventing novel problems without regard for what the answers/actualizations might be – how could it be otherwise in a creative situation? And we, as creative dance partners, are tasked with the careful inventing multiple experimental novel actualizations… The key is we are partners in a dance – sometimes they lead, sometimes we lead, other times the dance takes over… but it is always in relation – otherwise it is just AI parroting or us becoming small gods doing as we wish…

Do say: I’m working with a Bussoti score

Don’t say: Is this Beethoven, and I’m really confused – or is it anything goes and I’m really lost?

Have a wondrous experimental actualization of an astonishing week.

PS – if inspired, share your actualizations of the score!

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.