WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 222! Trans-Wor(l)dly Thickets...

Good morning becomings of conceptual labors,

This is the time when we really become winter (and summer) adapters.

Patterns shift in the whole configuration. We are organizing a new field of stable affordances and propensities. For us in the Northern Hemisphere, it’s boots for shoes. Socks get thicker and, on occasion, double up. We are all rummaging in the back of closets for favorite coats, sweaters, touques, and gloves. The tires need to change on the bike. And a battery conditioner is added to the motor.

The rituals of dressing and undressing at work, and in coffee shops, are getting complex – the multiple layers might be great for winter hiking and ice climbing, but not so much for city life. Big coats are far better.

Sensations in parts of the body emerge and are felt again for the first time in a year – the frozen nose, the pain of fingers and toes thawing out.

The relevance of the shape of the ground and building changes with us changing. Some buildings protect from winds, and others co-create piercing winds. The architectural stonework warms up so differently from the glass facade that we really feel the difference as we wait for the bus. The slight dips in the sidewalk welcome water, which will now stay frozen most of the winter – a new, dangerous slippery being we come to recognize and fold into our habitual patterns.

Winter – such a rich, dense, thick, and wide process of ongoing adaptation.

It is a beautiful word: adapt.

A word that speaks of change, processes, attunement, organization, affordances, propensities, and ultimately an ongoing co-creative world. We are, at every moment, engaged in creative responsive processes in a context that is equally involved in creative responsive processes.

So many critical terms come to swarm around the word “adapt”:

change

process

attunement

ongoing

responsive

involved

creative

And all of this brings us back to words. Words matter to creativity.

We in Emergent Futures Lab often think that in the development of words and concepts, not enough attention is given to prefixes.

Consider how things change when we add “co-” to creativity, for example: co-creative. Or co-adaptive…

The tone, feel – and what becomes relevant completely shifts. If we were to simply have the root, “creative” by itself – it would be all too easy to slip into the all too well-trodden path of individualistic and mind-centered approaches, patterns, processes, organizational logics, and propensities. Adding the prefix “co” to the root “creative” changes all that.

Co-creative.

Now we sense the pull of the agency of the environment, our tools, and others.

The great outdoors opens up:

Co-creative

Co-emergent

Co-adaptive

One of the significant challenges in developing a new approach to creativity is being able to develop concepts that alert users to their key difference – and keep users from slipping unconsciously back into an older usage of the term – we need to disrupt path dependencies.

For example, we can collectively redefine creativity to be a more expansive, non-individualistic, and collaborative set of emergent processes without changing the word.

But when we leave the word unchanged: “creativity” – in our current environment of organizational tools, practices, and propensities – it is hard not to allow it to slip back into the far stronger dominant logics of human internalistic individualism. Try it out: ask someone about “creativity” and then ask someone else about “co-creation” – we bet the answers will be worlds apart.

We often wish English were not what is called an analytical language (conveying the nuances of meaning via auxiliary words and word order), but rather an agglutinative language – where we could seamlessly add multiple discrete morphological units of meaning together to create new words. In German, we could fuse these words into one: “always-already-ongoing-emergent-co-creation” – and in a true agglutinative language such as Japanese, Inupiat, or Turkish, the fusion would be even more complete… Now we could easily get an alternative!

But we work with what we have – we hope that, as a longstanding reader of the newsletter, you are sensing these tacit compoundings of hyphenations and fusing in when we write “creativity”:

Creativity – it is always already underway, it is always ongoing, and without end, it is always collaborative, emergent, and exceeds prediction. And that even when things stay the same, that is also an astonishingly active ongoing creative processual achievement. Creativity is not something special we can occasionally add to the world through our unique gifts – it is what the world is and does – an ongoing worldly creativity.

We will often hear: “All of this is unimportant – it’s just words!”

“It's just semantics.”

But let’s not fall under the spell of this stupidity. First, semantics is about the meaning of words, and meanings do matter.

But perhaps the bigger tacit misunderstanding is to think that words are not fully and totally connected to practices. Meaning is use. Using words is never about “just words.” Because words are worldly. Words work very hard in all human systems. Words live in the thick of things. Words are in the dirt under our fingernails. And in the strange sounds we make to call our cat. Words resonate deep in our bodies, pulling us into action. They connect and activate, unlike practices and processes. They hold together and open up nascent propensities. Words leap between bodies, muscles, and actions on a sailboat in a storm to activate and co-ordinate disparate practices through tone as much as semantic meaning.

Words find their agency in heterogeneous networks – they do not live in some removed ethereal gated community of scholastic angels.

Words are never “just words.”

Words are tools – very much like a hammer, alphabet, or an ocean current – while they are neither good nor bad, they are most certainly never neutral.

We work with words – concepts – and as we do, concepts work on us. Using words is never about getting a definition right (a dangerously purified semantic violence of headmasters)-- or just as problematically emptying words of meaning (here is a good example of this from our orange poet, start at minute 2:55). It is not about demarcating, enforcing, or obfuscating the so-called correct usage. Nor is the “natural” essential usage of language “communication” (the relaying of abstract information accurately between two parties). Rather, from the perspective of creativity, it is, like with all tools, about figuring out what they can creatively do in a certain larger heterogeneous configuration.

This week, we are returning to our occasional series on concepts (see our experimental glossary on the website). And in this newsletter, we look back at some of the conceptual tools we have introduced in the last three newsletter series: On Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus, On Blocking and On Engage (from Volumes 206 to 221). This week, our goal is to introduce a few key terms that can help us contrast the classical Western human individualistic and essentialist approaches to creativity with more distributed and emergent practices.

Let’s start with two words that use another of our favorite prefixes: the wonderful trans:

When we, as precarious embodied beings, engage with things – when we do things – we meet a creative relational reality as neither objective nor subjective. Reality is neither fully separate from us (objective – simply “out there”)) Nor is it reducible to us (subjective – our illusions, imaginations, or “best guesses”). Instead, because of how we are actively of an environment relationally, it shows up (really simply exists) with relational but very real qualities. And these real relational qualities are better understood as what Veraeke and Mastropietro term “transjective”.

“What is relevant to an organism in its environment is never an entirely subjective or objective feature. Instead, it is transjective, arising through the interaction of the agent with the world. In other words, the organism enacts, and thereby brings forth, its own world of meaning and value.” (Jaeger et al)

A simple example: To a person jumping into a swimming pool on a summer day, they are met by a liquid that surrounds their body, slowing them down and ultimately suspending them in the water buoyantly. But to a small water skimming insect – a Water Strider, it is not experiencing that very same water as a liquid that they float or sink in whatsoever, but rather as a tensile surface they can skim across as they are stuck to it electrostatically. Then, changing scale again – to a paramecium, the very same water that is a very thin fluid to us – is quite a thick, syrupy substance. And to a single-cell bacterium, this very same “water” is experienced as something that is not a liquid at all – they are bounced around by molecules.

The reality of our experiences profoundly shifts relationally as well: if we as embodied humans now decide to dive into that same pool of water from a very great height, nothing about the objective physical properties of the water will change, but when our diving body now meets the water, it will not part around our body and gently slow it down. The transjective experience will be one of hitting a very hard, solid object that will crush our bones and organs, no differently than hitting a concrete sidewalk from a great height.

In all these cases, it is the same “objective” physical thing, “water” – but the very real and consequential experiences are wholly qualitatively transjectively different. Another way of saying this is that given the relational organization of our practices, bodies, tools, and environments, reality will show up in ways that afford us very different real experiential possibilities (see Affordances).

Additionally, what is relevant about our embodied selves, our practices, tools, and environments will radically shift. Importantly, especially from the perspective of creativity, we – like all living beings – live in a dynamic, concretely real co-created transjective world. We do not experientially ever meet an “objective” world – nor is our subjectivity ever separate from this transjective reality (see World-Making).

See Affordance, Organization, Relevance Creation, World-Making, Assemblage, Emergence, Bio-Encluturated

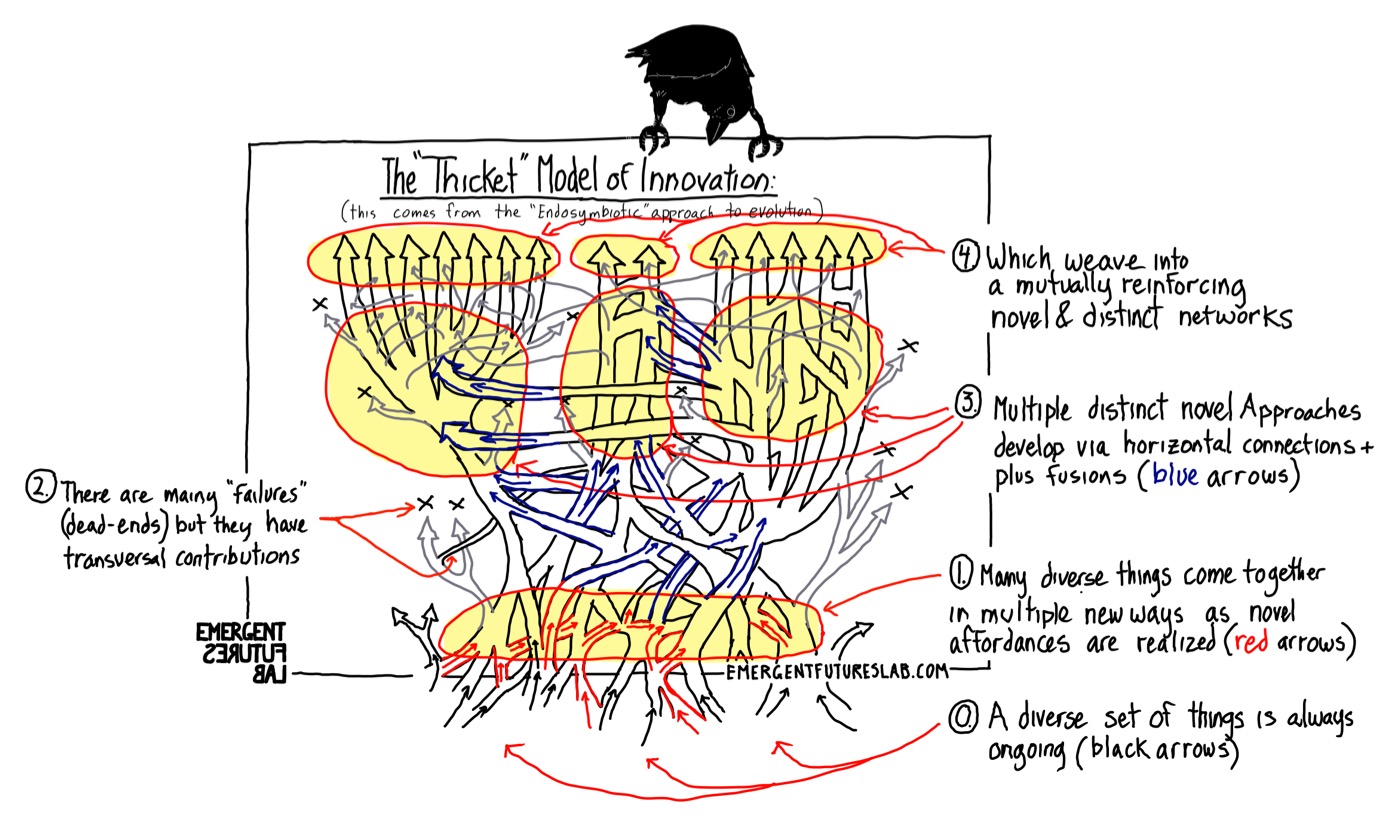

Innovation begins thick and wide. It does not have a single source that sets it all into motion – there are no silver bullets. It is never beginning in one thing, one idea, one experiment, or one person. The linear and future backwards approaches to creativity that begin with projective ideation cannot objectively lead to the new (see Emergence). Creative novelty emerges from an already ongoing dynamic, rich, diverse, and deeply horizontally entangled ecology where novel possibilities of new relevance realization can co-emerge in startling ways. Of course, in human engagements with creative processes, there will be many unique moments of insight and inspiration – but they are never separate from a thick and wide entangled milieu.

This dynamic, rich, thick space of diverse becomings is our ongoing reality. As a novel “matter of concern/curiosity” develops in the midst of ongoing life, new transjective possibilities begin to emerge as relevant and transversally connected.

Creativity can never be reduced to a single point (as the double diamond approach to creativity might imagine). But instead, it will be the thick and wide transformation of many entangled ecosystems – that will always remain a thick, wide, and deeply transversally entangled rhizome without end (see Transversal).

For creativity, the question is not “how to have a great idea” or imagine a revolutionary outcome. No, creativity asks us to collectively engage in ways that find, support, develop, collaborate, and co-evolve with an already existing transversal thicket such that it can configure in ways that can spontaneously allow for the co-emergence of novel adventures of relevance creation.

See: Transversal, Thickets, Rhizomes, Enabling and Stabilizing Configurations

If linear, projective, future backwards approaches to creativity will not give rise to novel outcomes (see Psychological Creativity) – what is an effective alternative way to engage with creative processes?

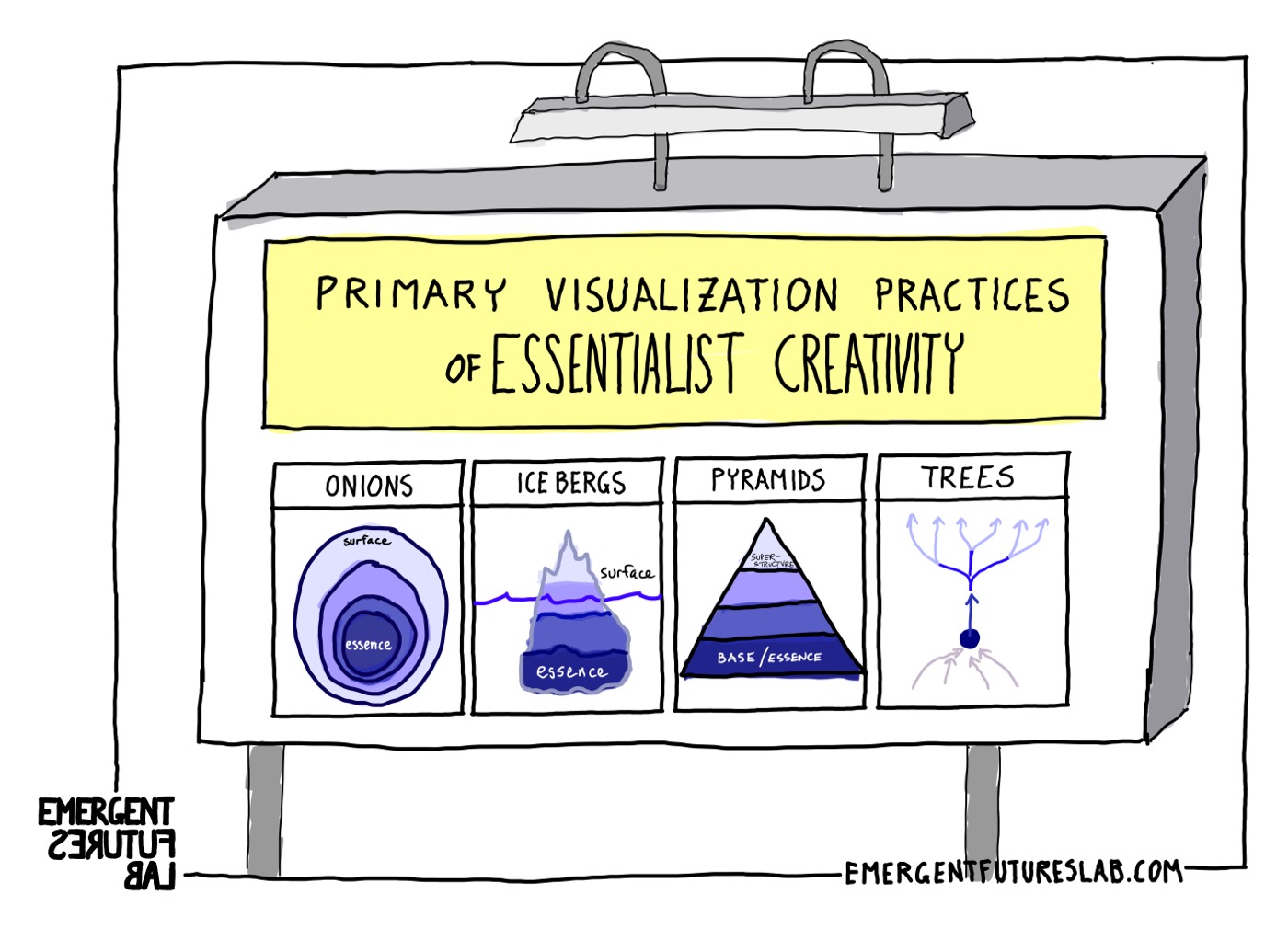

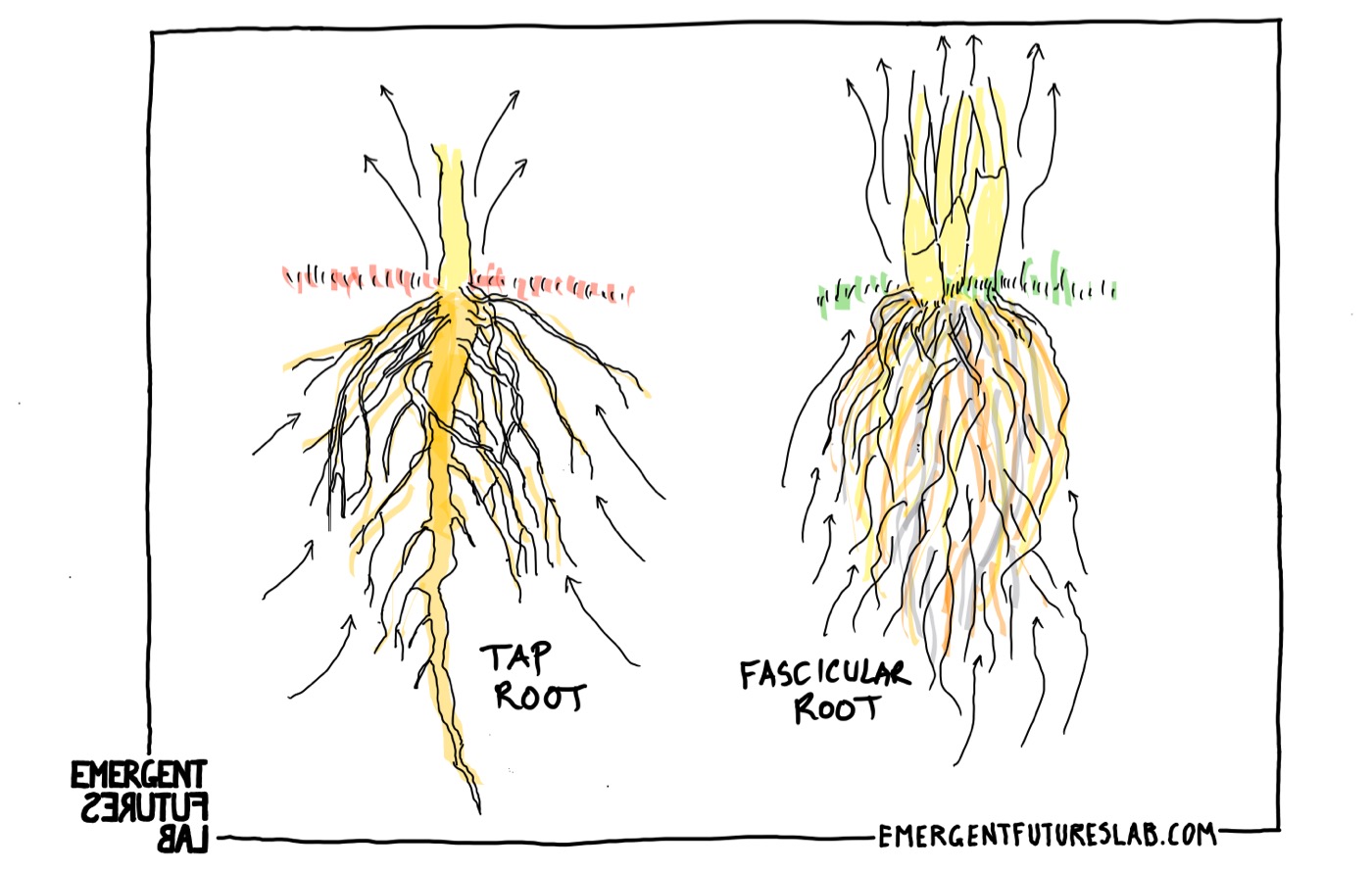

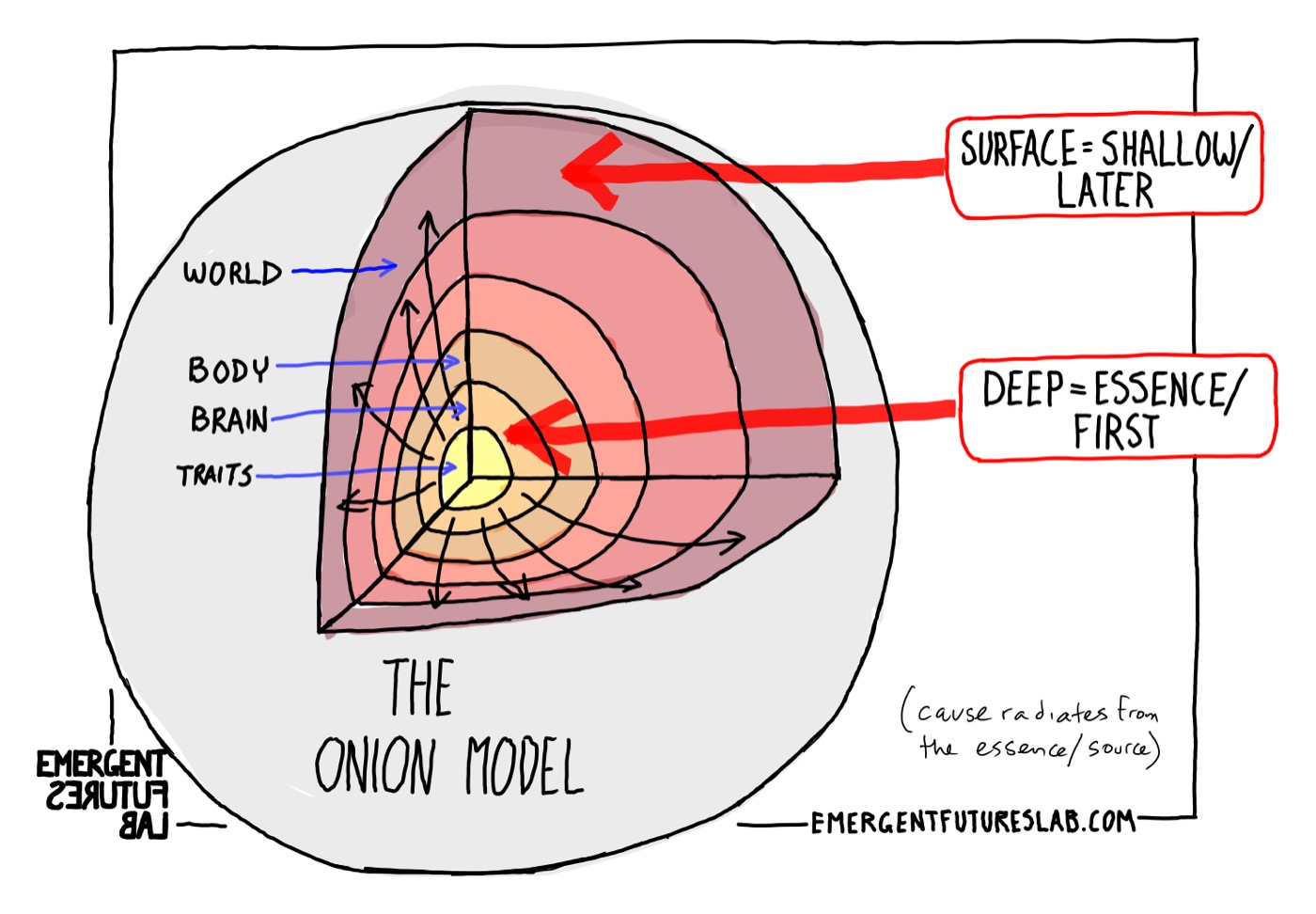

For this, we need new guiding metaphors. If the reductive and essentialist metaphors of classical individualistic creativity – the tree, onion, pyramid, and iceberg all lead us astray, where can we turn? A very helpful contrast to the tree with its convergent roots is the Rhizomatic root with its transversal spread.

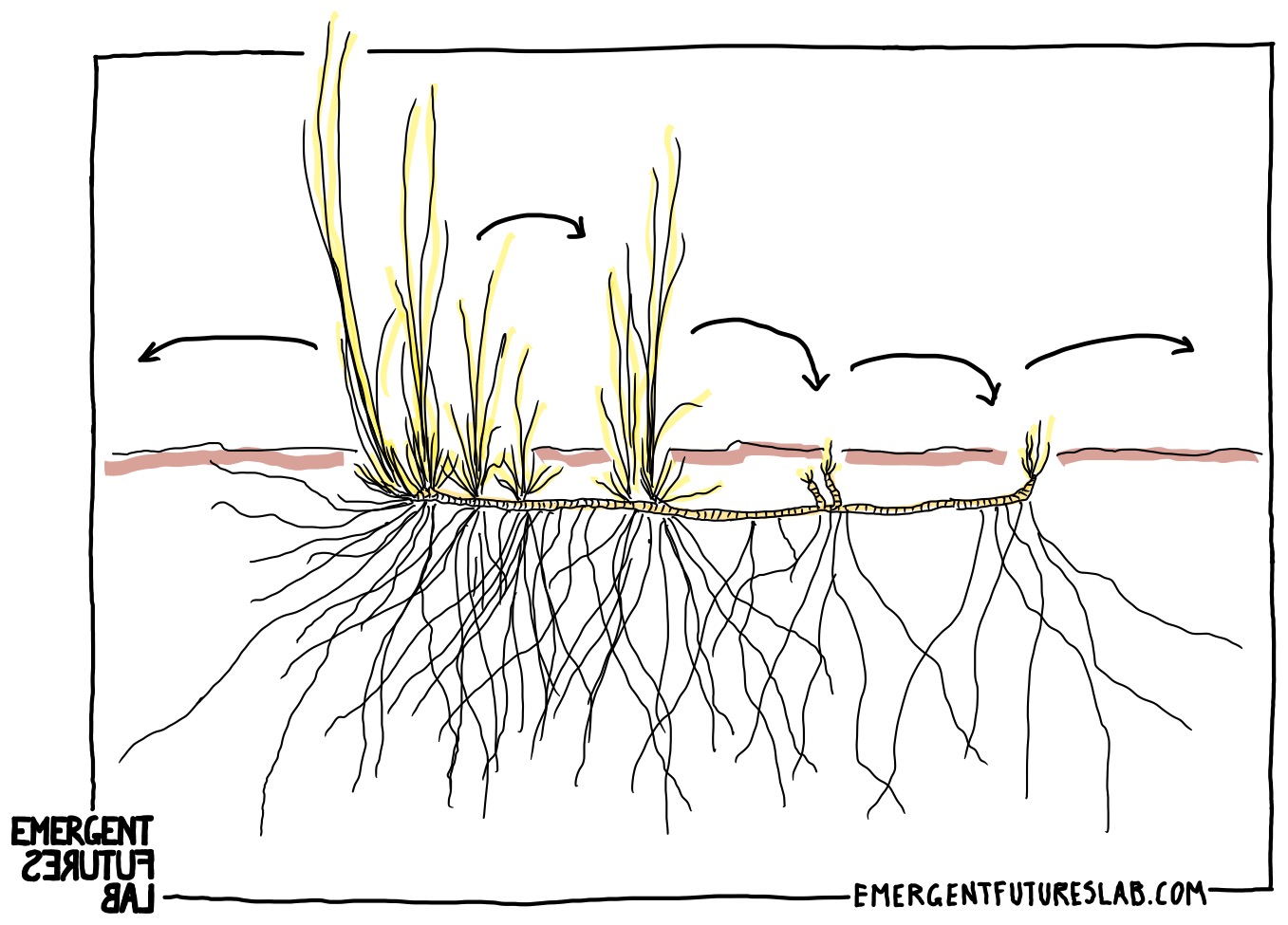

Rhizomes are also rooting processes, but they do not converge on a single plant stem or tree trunk – rather, they can infinitely diverge, wander, and multiply. Rhizomic plants have no center, no single source, nor final form:

The examples are vast: corn, dandelions, bulbs, tubers, mushrooms, and some trees (such as aspen) are all rhizomatous. And to this, we should, following Deleuze and Guattari, add: rats, wolf packs, and even their burrows.

Here we have a new image/metaphor of creative processes – as an open-ended, relational, and ever-changing creative process, which can be understood as:

See also: Transversal, Transversal Thickets, Thickets, Trees

What if creativity began not with the individual, but with the field of relations?

A collaborator is not simply a person who joins a team, nor a discrete actor who brings their skills to a table already set. Instead, a collaborator is an emergent participant in a dynamic, ongoing process of co-creation—a node in a web of relations, shaped by and shaping the collaborative event itself. To be a collaborator is to be made by collaboration, as much as to make through it.

A collaborator is any agent—human, non-human, material, conceptual, environmental, or technological—that participates in the emergence of a novel assemblage. Collaboration is not a secondary act added to pre-existing individuals; it is the primary mode of being from which individuals, ideas, and outcomes emerge. The collaborator is both a product and a producer of the collaborative process, inseparable from the relations and processes that constitute the event.

A collaborator, as a node in an emergent ecosystem, is ultimately created by the relations.

See also: Emergence, Ecology, Configurations, Organization

The Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ) is a rhizomatic concept first coined by Hakim Bey in his 1991 book of the same name. The concept offers a vision for an alternative creative process: a momentary assemblage where dominant structures and practices are set aside, roles are reconfigured, and something new, messy, and uncertain can potentially emerge. Temporary Autonomous Zones are where highly transversally linked networks can gain autonomy and agency to disrupt more well-established linear and neatly segmented practices. Their logic is temporary by necessity. They run in parallel – often within dominant structures, and are highly ambiguous. But if and when novelty might emerge, they can transform to stabilize into a novel ecosystem.

See also: Rhizomes, Transversal Thickets, Emergence, Apparatus/Dispositif

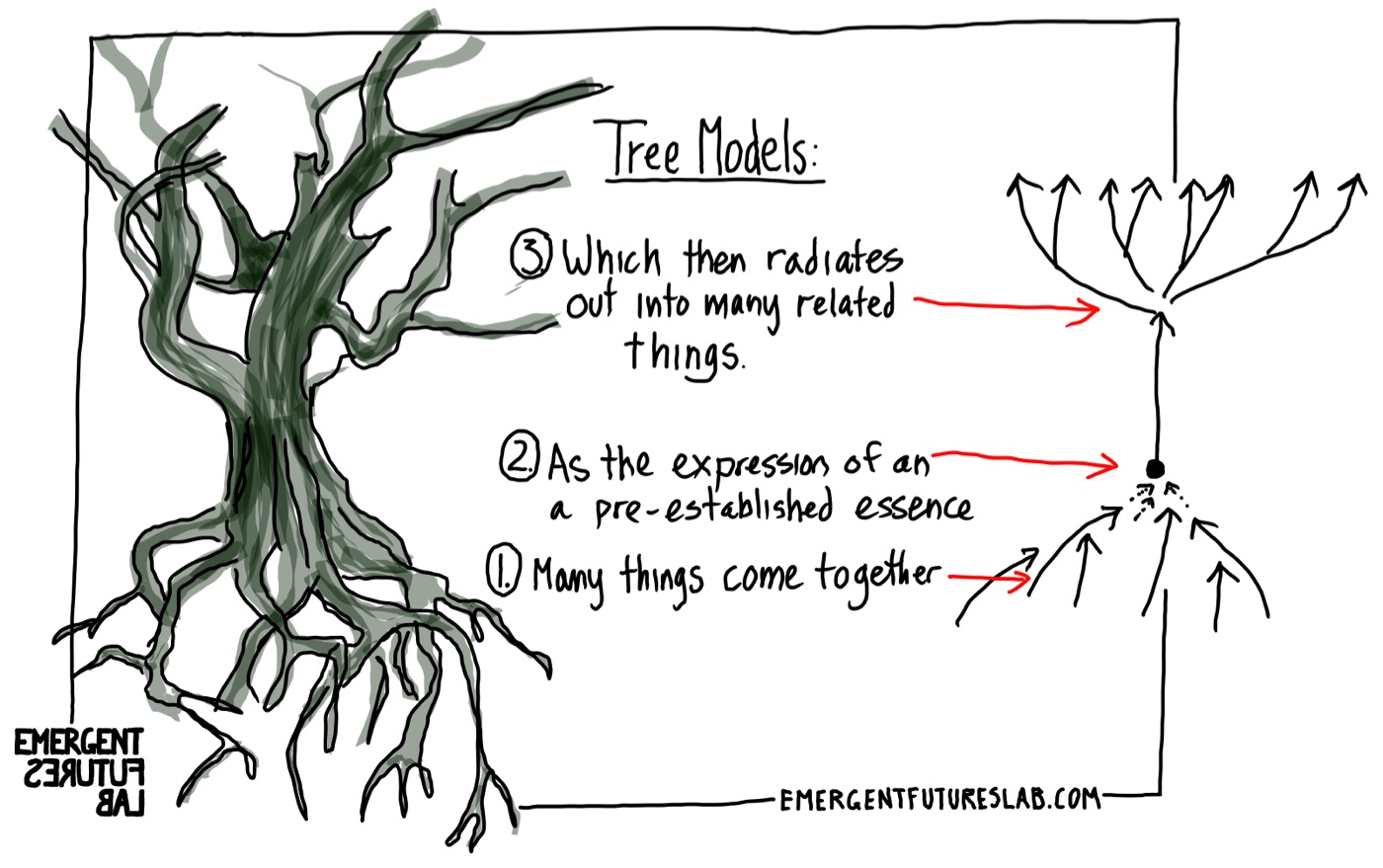

Tree models are one of the four classical and deeply problematic reductionist/essentialist ways of presenting the creative process (the others are the multi-level pyramid, the iceberg, and the onion).

Tree metaphors have two operational logics in relation to creativity: (1) the Seed, and (2) the Root-Tree.

Seed Metaphors and Creative Origins: The seed gives us the paradigm image of a discrete source – a discrete self-contained essence that holds all the necessary information to generate the final outcome (the mature tree). But seeds don’t work that way – they simply do not magically turn into trees alone – humidity, temperature, fires, animal digestion, fungal networks, soil, tree relationships, and much else are required in a continuous and ongoing manner. And then we are back to the transversal thicket and its entangled emergent possibilities. Seeds as part of very specific, contingent, thick, and wide assemblages will, with great good fortune, open up the propensity for a tree becoming.

And more than that, the seed has no fixed relation to the tree. The seed does not equal a tree – it could just as easily become pig food or be used to make ink, or be crushed into soil. Or digested by bugs, fungi, and worms. And again, things always move sideways – transversally far more than linearly.

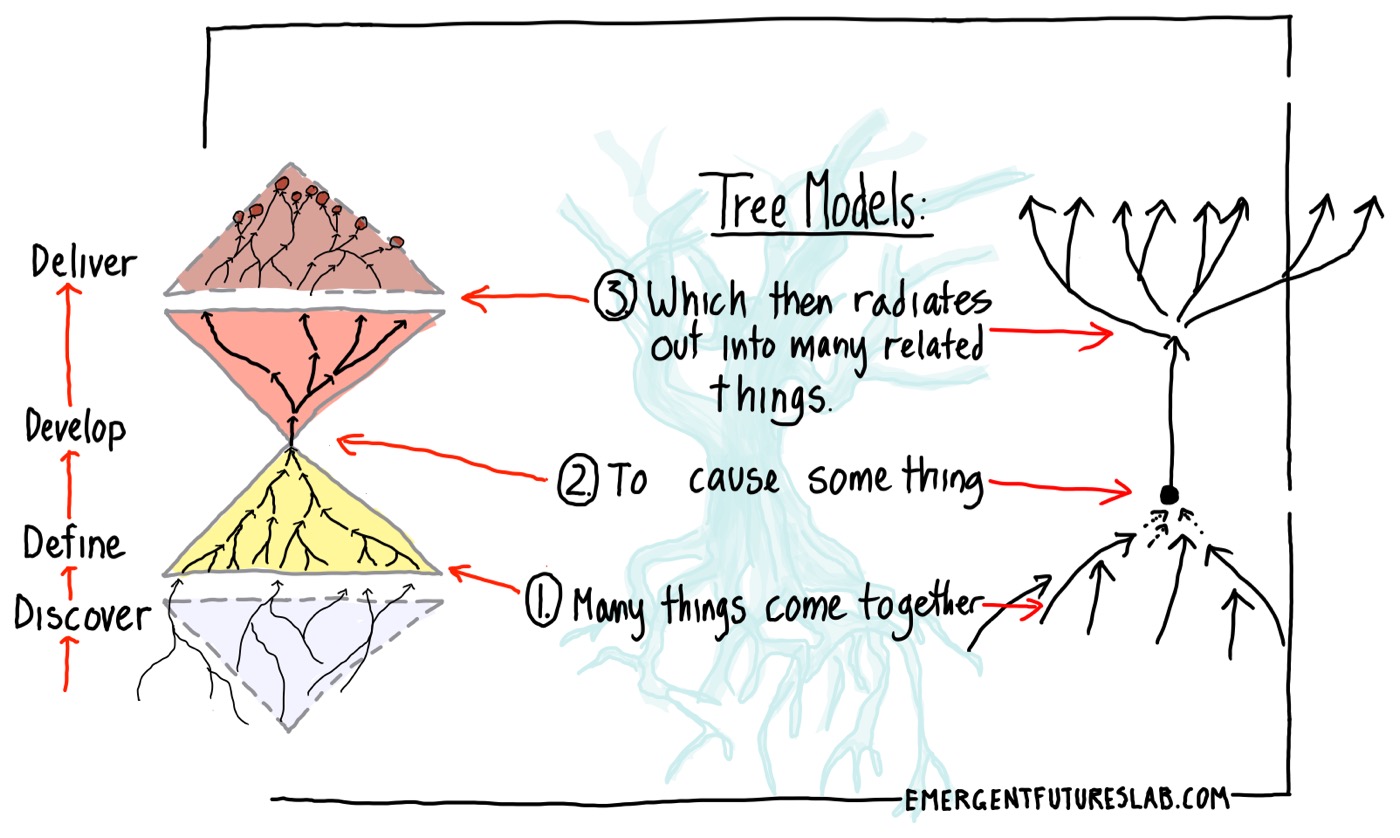

Tree Metaphors and Creative Processes: Tree models offer a three-part metaphor of the creative process: (1) Roots as Convergence, (2) trunks as the Core of the New, and (3) Branches as the Divergence and spreading of the new.

Why roots? This metaphor activates how roots lie hidden beneath in the soil and “give rise” to visible things – trees, plants, flowers, bushes, and weeds. Simply put: Roots give us one image of the creative processes of becoming: from the many to the one. The many could be research, empathy, or preparatory inspiration – any form of preparation. And then creativity bursts forth into the light as a singular, powerful thing:

And this leads to some pivotal eureka-style moments of ideation/imagination. But, again, this is more mythic than actual: The highly distributed configuration is giving rise to the possibility of ideas emerging in a thick context (and again, we are once more in the processes of transversal thickets).

But this metaphor does not end here: The Trunk becomes an image of the singularity of creative outcome, idea, and imagination. Which then radiates out into many possibilities:

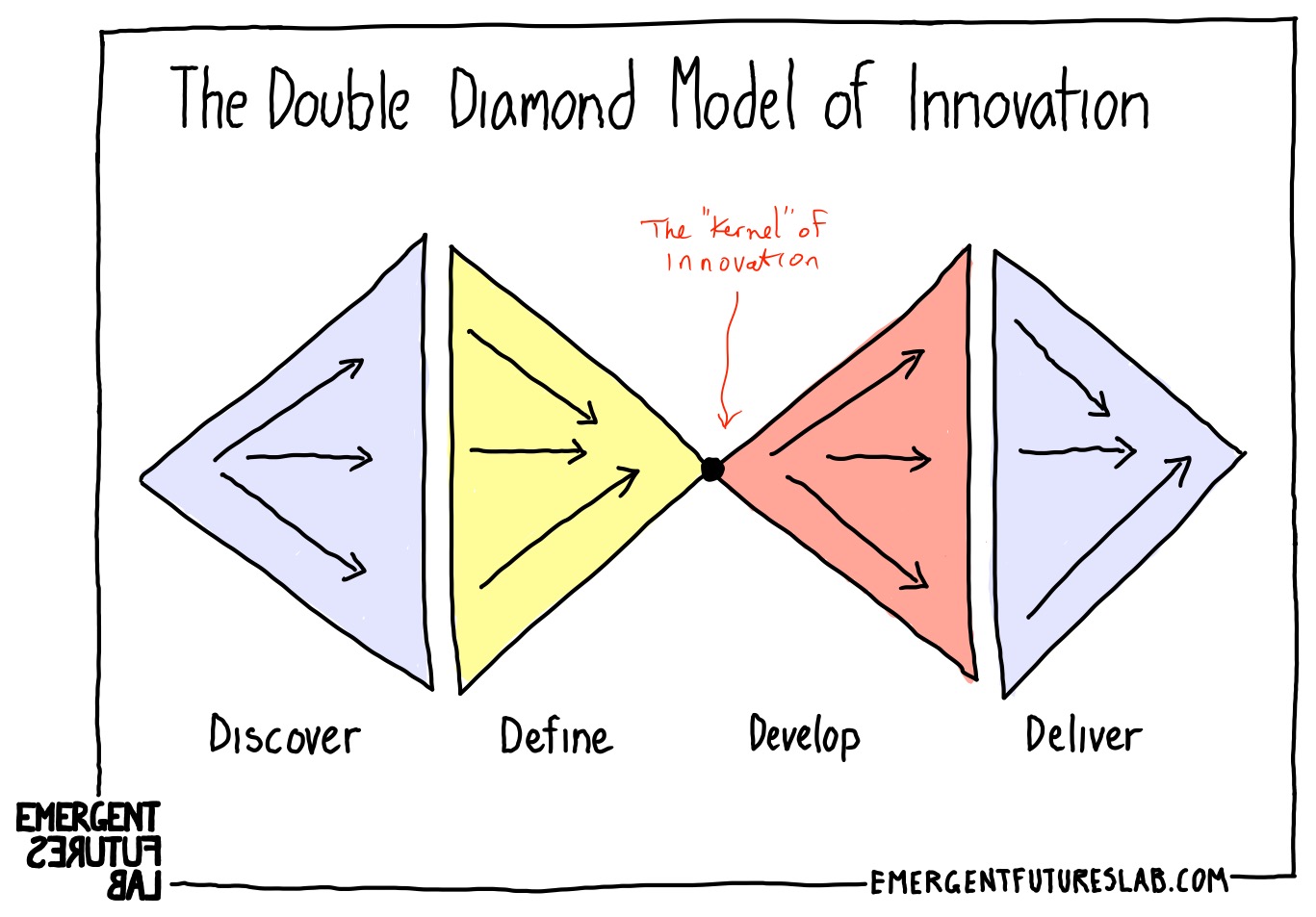

Perhaps the most famous contemporary model of these tree logics of the creative process is the “Double Diamond” (which is also one of the most ubiquitous and problematic images of a creative process):

How are these diamonds a tree? – We just need to turn it on its side to see this:

Ultimately, what is the issue with the tree model of creativity?

The tree logic is a process by which imitation, representation, and reflection work, where the many novel differences are forced to become one and then forever reflect the one. What is the problem with this process? It is a process not of creativity but of forcing differences to correspond to a tacit pregiven assumption that underneath all of the surface differences is sameness – a common essence: The many become one, and then one becomes the many as only variation in degree.

The double diamond, like so many purported creative processes, is in fact an anti-creative process unconsciously designed to produce imitation. It is unhelpful if our goal is to engage with creative processes. Trees are “over-coding” processes of producing sameness.

We need new approaches and guiding metaphors – and these ultimately start with the transversal, transversality, thickets, and rhizomes.

See also: Transversal Thickets, Transversality, Rhizomes, Emergence, Configurations, Assemblages.

Traits, as in Trait Psychology, is an approach to understanding human individual subjectivity or what is commonly termed “personality”. This approach posits that human actions can be best understood and explained via the positing of deep, fixed internal personality traits. Such a theory offers an essentialist and reductive approach to human subjectivity, personality, and actions. Why do we do bad things? Why are we late? Why are we empathic? Why are we creative? It’s the way deep down we just are… (or so this approach claims).

This essentialist approach activates an “onion” metaphor that posits that underneath the various superficial layers of the self is a deeper, unchanging core.

Despite overwhelming evidence, far too many organizations hire, judge, and train employees based upon a trait-based approach to job aptitude (over 80% of Fortune 500 companies).

The most common of the trait models is the “big five,” which classifies personality in relation to the traits of Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism.

After countless studies, there is little correlation between observed behaviors and how individuals are rated by various trait-based models. The research in Social, Ecological and Situational Psychology has shown that our actions, and “personality” are far more dynamic and variable than a trait-based approach would suggest. Countless studies, the most famous being Stanley Milgram’s teaching experiment, have conclusively demonstrated that our actions are best understood to be the emergent outcomes of many distributed environmental factors. Why we act in a moral or immoral manner is not because of any deep internal moral trait but because of an emergent interplay of environment, tools, practices, and habits.

Trait-based approaches have had a detrimental impact on approaches to creativity in that they ascribe to individuals what should be properly ascribed to the configuration of an assemblage that includes people, practices, environments, and tools (see Fundamental Attribution Error). We see this error writ large in the romantic ideal of the lone creative genius.

See also: Fundamental Attribution Error, Configurations, Emergence, Affordances, Bio-Enculturated, Onion Models, Romantic Creativity

The development of creative processes is profoundly hampered by a human, individualistic, and internalistic approach that mistakenly attributes emergent ecosystemic outcomes solely to the individual and their internal qualities (traits). In regards to creativity, this goes back to the initial development of this concept in the 1800’s as a form of Romanticism's logic of the “Genius.”

It's not that the individual does not exist – that we are just an epiphenomenon of the highly distributed relational dynamics of some system. It is simply that we exist of and through intra-dependencies that can be profoundly changed but cannot be removed.

“There is no autonomous subjectivity… Agency, when embodied in living beings, can acquire experiential content… but this awareness of agency, characteristic of human bodies, is largely an illusion. There is no agent apart from action. Agency is not a permanent feature or property that someone has independently of situated actions, but the emergent product of material engagement… as a creative tension of mind and matter or flow and form.” (Malafouris)

See Traits, Configuration, God Model, Romantic Creation, Bio-Enculturated

To be bio-enculturated is to exist as an inseparable weave of the biological and the cultural, where neither domain stands alone nor acts in isolation. The term signals a profound entanglement: our bodies, habits, desires, and even our sense of self are not simply given by biology or shaped by culture, but are co-produced in a living, ongoing process. We are not biological beings later draped in culture, nor are we cultural agents riding atop a biological substrate. Instead, we are always already bio-enculturated—formed in, through, and as the loops of soma and society, matter and meaning, flesh and form.

“The biological, bodily and the social are not separate levels “but processes linked in a spiralling interweaving at three temporal scales: the long-term phylogenenetic (we inherit a plastic capacity for living in interdependent niches), the mid-term ontogenetic (we develop our embodied capacities as we are embedded in practices), and the short-term behavioral (as developed bodies politic we act and react to our material and semiotic encounters)”. (John Protevi)

Bio-enculturation names the condition where the biological (our bodies, brains, nervous systems) and the cultural (our languages, practices, technologies, values) are so deeply interwoven that they cannot be separated without distortion. This is not a layering of one atop the other, but a dynamic, recursive process: our bodies are shaped by cultural practices from birth, while those practices themselves emerge from and reshape the living bodies that enact them. We are “of things, not in them”—participants in a cosha (a biosocial something) that is always in the making as it makes us.

We could go on with concepts – there are so many in these last three series. We will pick these up in the new year.

But, we are coming to the winter holidays – in just over a week, we will be celebrating the Solstice! And shortly after that, the Gregorian New Year. And so it is worth slowing down, recognizing, and celebrating the intra-dependent arising of all things (Pratītyasamutpāda).

We can move away from individualism, reductionism, and essentialism in all things – especially in regards to creative processes – and instead celebrate our thick, wide, relational, entangled – trans – creative emergent becomings.

Till next week – keep entangling, going sideways in all directions to celebrate and welcome creativity in every moment of our excessive collective and highly surprising becomings.

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.