On the Young Life of the Concept “Creativity”

When Jason and I mention to people that the word “creativity” is of very recent origin in the West — being first used in the 1850’s and only becoming part of our everyday English somewhere between the 1930’s and 60’s — we’re met with incredulity.

The most common first reaction is “that cannot be true.” And when assured that it is, the next reaction is, “well they must have had some other word for it”.

When we try to reassure them that they did not — then the incredulity really sets in — “How could this be? Every culture is creative so they must have had the concept!”

The Fine Print

Up-front we need to clarify a couple of things:

- What do we mean by “creativity”?

Contemporary definitions of creativity focus on the concept of “the human making of something genuinely new”. And if we take this as a basic definition, then — the very concept of creativity did not exist in the west until sometime in the 1700’s.

- Creativity and Creation are two different things.

Creativity involves the making of something new, and creation refers to the process of making in general.

- Weren’t the Greeks making new things? What do we mean by the claim that in the western tradition the concept: “humans can make new things by their own power and imagination” did not exist prior to the 1700’s?

We hear this rejoinder often: “This seems crazy, weren’t the Greeks and the Europeans making all sorts of new things, and concepts that were really new and different?”

That is certainly correct.

What matters for this discussion is how did they understand what they were doing?

Did they understand that they were being “creative”?” If the answer to this question is yes — then they had a concept of creativity, and if the answer is no — then they did not.

Historians tell us pretty clearly that they did not conceive of what they were doing as being creative. (We will get into what their self understanding was in a moment).

- All of which brings us to an important point: for us as a contemporary culture, creativity is something of great importance, it is a very positive attribute, and something we understand to be universal (we in general believe that it is in all people and all cultures). But, here we need some cultural humility — why are we ascribing our (current) values and concepts to all people everywhere and at all times? Can we just do this prior to rigorous research in good intellectual faith?

When we ascribe our values and concepts to others are we losing sight of the fact that there are other ways to be alive?

Other ways of being alive do not necessarily share any of our habits, practices, values and concepts. To think otherwise prior to research risks a dangerous cultural and historical imperialism and erasure of difference.

We live in a world where many worlds exist. And because of this we know that genuine differences exist:

- Qualitative differences

- Ontological differences

- Worldly differences.

Our most cherished concepts are not universal. Nor are they ahistorical. Other cultures and other eras live and have lived in very different ways. To believe otherwise leaves us assuming that everything and everyone is just a variation of the same. And that these variations all happen to be confirming our default starting values, concepts and assumptions…

…and nothing could be further from a creative position than this…

Let’s turn to the Greco-European history of making with a curiosity and humility that comes from knowing that qualitative differences exist.

What is Greek Making to Creativity?

It is best to go back to the classical Greeks to answer the question, “did creativity always exist in the west?” — because of the profound influence their concepts had and continue to have on Western Asian thought (or as it is often also called: European thought or Western thought — there is no ideal term but we like “West-Asian” because it connects the region to the continent, notes its cardinal location (west), and locates it in a larger set of theoretical debates that have flowed historically across Asia).

We know quite a bit about Classical Greek concepts on the topic of creating/making from the writings of philosophers and playwrights, politicians and poets.

Creation is a word of Latin derivation, the Greek word for making was poiein. Our word poetry comes from this word as does autopoiesis (self making). This word covered all forms of making from the making of written texts, to ceramics, to a house. All making was of the same sort — they had no concept or word that would translate our modern concept of “art” or “craft.”

For each area of making there was a need to learn a set of skills, and practices of making (techne— from which we derive technique and technology). Techne was always aimed at making the perfect or ideal version of whatever was being undertaken (arete).

The critical question that Greek makers asked of themselves was “how do we make (create) something perfect”? This is a very different question from “is there a better way to solve this problem?” Or “is there a totally new way to address this issue?”

For the Greeks the perfect was the true. Truth had to be something both essential (getting to a singular core answer) and unchanging. This meant that truth is an ideal immaterial essential form.

It is worth noting in passing how different this is from a contemporary “correspondence” model of truth, where a statement (for example) is true if it corresponds accurately to how things are.

All of Plato’s Socratic dialogs are stories about the collective search for the essential and immaterial truth: Socrates asks various people “what is X?” — with X being beauty, truth, love, justice etc. They answer, and he criticizes them for only offering examples but never getting to the true essence. For while Socrates claims he knows nothing, and this famously makes him according to the oracle at Delphi the smartest Greek, he does know the form any right answer must take. To be true it must be the pure immaterial unchanging essence that sits behind any actual worldly and changeable example.

The Two World Model

In this manner the Greeks bequeathed West Asia with a two world model of reality: one of pure immaterial ideas (ideal essential forms) and the other of changing inherently imperfect matter (the everyday world we live and make within).

This model continues in many of our most cherished assumptions and values about the immaterial nature of truth and ideas and their place in our actions.

With this model the perfect is always immaterial — an “idea” that does not change. And with this model we have the basic logic of Greek making: we need to see the ideal form and copy it. Making is aimed at perfection and perfection is found in an immaterial ideal that can be copied.

This is why historians can clearly say that the Greeks did not have a concept of “creativity,” because in their self-understanding of reality nothing new is ever made.

For the Greeks at the beginning of time there were already in existence the ideal unchanging immaterial forms — and everything that exists in our world is an instantiation or copy of these forms. This is ultimately a closed universe where all life “follows” from a pre-existing set of ideal forms.

The Greek Model of Creation

In this world, a good maker seeks to gain access to the ideal itself. This happens via a techne and the help of the muses (what is later called “inspiration”— but not in the modern sense of the term). Once a good maker has been granted access to the ideal, they can then copy it as best they can (here the whims of the gods play a role).

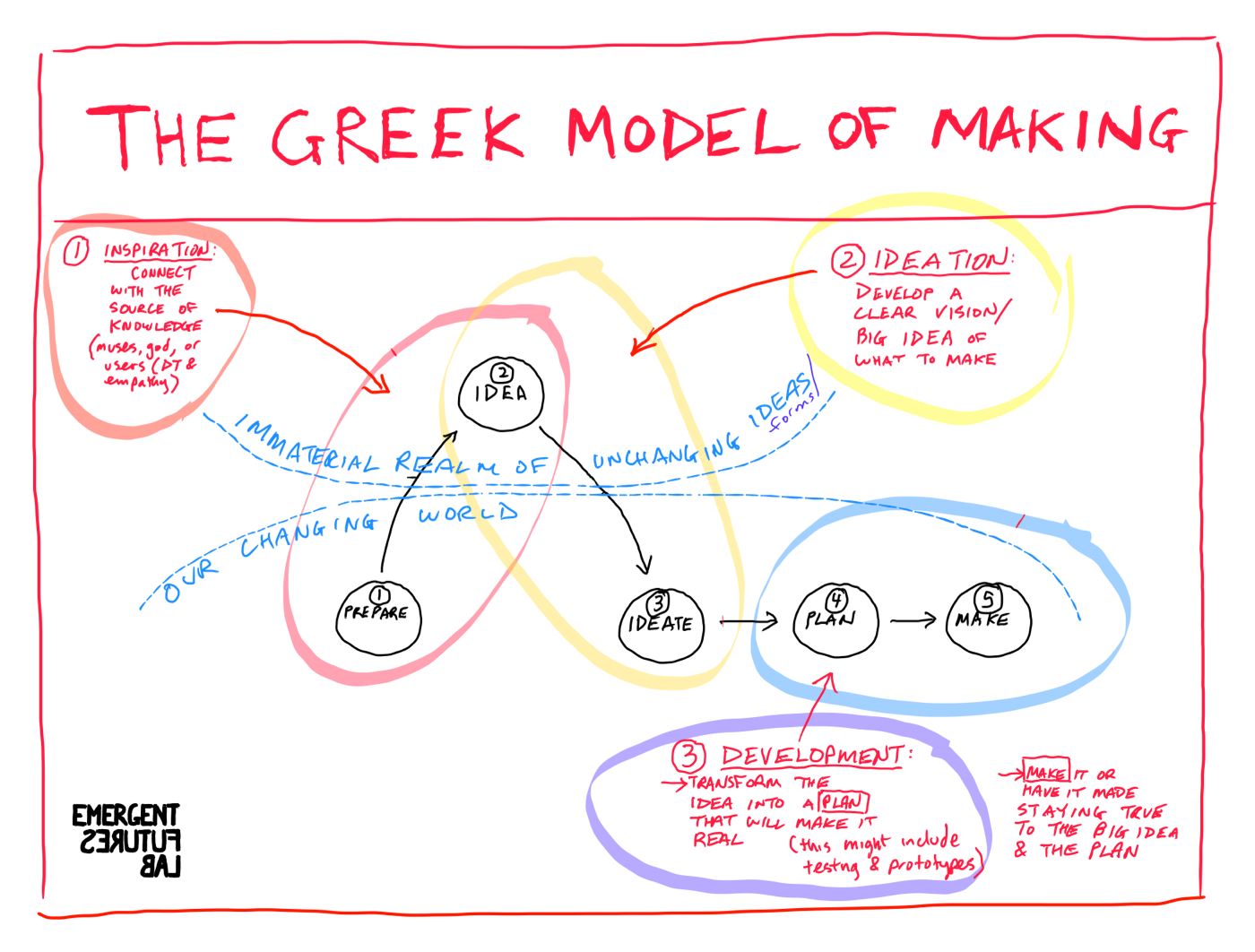

The model has three phases:

- Inspiration: preparing and being granted access to the ideals

- Ideation: transforming what is seen into an idea/vision in the individuals mind

- Development: undertaking the process of making it real via a plan, selection of appropriate materials and their forming

A poor maker is someone who looks at things in our mundane world (vs the ideal realm) and seeks to use these things as a model to copy. Plato was strongly critical of painting, poetry, and theater because they tended to focus on copying what was seen in our mundane world — and thus the practitioners of these forms of making were mere copiers of copies.

A great maker in Plato’s writing was someone who could contemplate the ideal forms directly — someone who did not make at all. This led to a divide that persists today between those that merely make and those that “think”. Thinking is still far more valued, and only lesser folks need to get their hands dirty. Board rooms ideate and then the task of making is delegated out to others. This logic also persists in “ideation first” models of creativity that put the engagement with concepts and ideas prior to forms of making. In many ways this is something that is today wholly implicit and thus quite hard to even understand as being something that has a history and could be problematic.

In Plato’s ideal we can already see hints of what the problem is for us today with this model of “creativity”: abstract thinking is of great value if your aim to to uncover fixed ideals — but if your goal is to do something new, then perhaps abstracted thinking (in whatever form it takes) will be far less helpful. A critical question for the creative process is “can the really new even be thought (ideated) whatsoever?” (But, here we are rushing ahead…)

In the Beginning…

“But, for the Greeks, how did they imagine that this world of ours came into being? Surely our reality could not have been created from nothing?”

Plato discusses how things originate and come into being in the Socratic Dialog Timeaus. Here it is posited that a good god formed our reality based upon the perfect immaterial forms found in the ideal realm (which resided in the mind of this god). The material world prior to this was a chaotic mix of the basic elements.

Aristotle later develops this god into the concept of the “unmoved mover” who then becomes the model for the christian god in the work of Aquinas and the Scholastic tradition. It is a god who sits outside of creation.

The god becomes the first creator/maker who imposes a plan drawn from the ideal forms he possesses in his head, and imposes them upon passive matter. But importantly — even this god was copying…

Imposing Form of Passive Matter

This concept of a god who creates from ideal forms gives rise to the “god model” of creation. The anthropologist Marshall Sallins describes this model well, “this is a heroic model of creation involving the imposition of form upon inert matter by an autonomous subject, whether god or mortal, who commands the process by a presetablished plan…”

Between the Timeaus and Aristotles later work the basic model of making, that in its most general form continues to this day, was laid out:

- Prepare: gain insight, inspiration — connect with the source of immaterial knowledge (via the muses, god, trends, users via empathy, etc…)

- Ideation: develop a clear abstract and immaterial vision/big idea of what to realize

- Development: Transform the idea into a plan (this might involve prototyping or future backwards planning, etc.)

- Make: impose the form on the best suited passive matter

And in following this model it’s fundamental assumptions still exist:

- Ideas, abstractions and the immaterial realm matter most

- Matter and the world around us is essentially passive

- Form is given to matter via an imposition from the outside

- You need to — and can know, in advance of doing

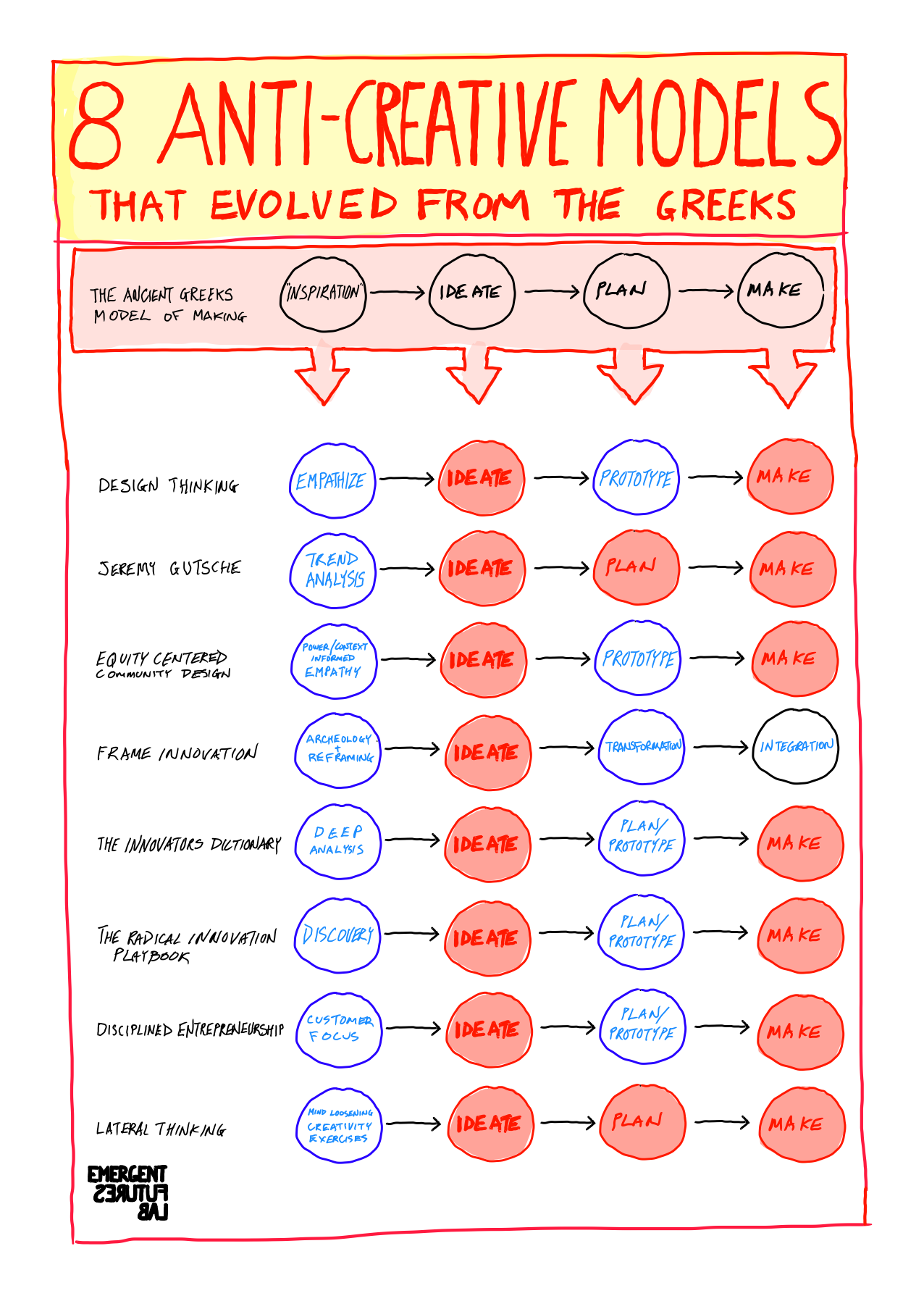

We see this very general model and these very general implicit assumptions in almost every aspect of the contemporary creativity and innovation landscape (there are some key exceptions, which we will discuss at the end).

Can we really say that the greek model of making is in nearly every contemporary model of creativity?

For us what is important is that it the model is there at a very general tacit level and that the basic assumptions of (1) the value of ideation, (2) a human mind centered focus, (3) that matter is neutral/passive, and (4) the process goes from being in general more involved with ideas to being more involved with making — are equally implicitly present. Obviously, when we get into the details of these and other methods they do differ. But the question remains, and it should concern us: why do most contemporary models of creativity follow in broad strokes a Greek model of making that was never intended to lead to creative outcomes — but to the very opposite?

Now there are other key aspects to the Greek model of creation:

[1] Nature (all living things) are active in striving to perfection or to realize their inner essence.

[2] Internal essences: Aristotle brings the immaterial ideal forms down from a separate realm and puts the essence in each and every existent thing (the onion model).

This becomes an essential method in the West Asian conceptual toolbox: reductionism. The process behind this model of inquiry is one of seeing through things (and ignoring them) to find what is behind them, of peeling off the superficial layers and digging down to uncover — all to find the hidden immaterial essence. We engage reality as something to see beyond and to strip away like the peeling of an onion. This model leads to a worldview of seeing discreet things with internal essences (vs for example, a relational model of reality).

[3] Progress: The Greeks organized reality into a hierarchical “Great Chain of Being” where everything could be organized along one vertical axis of ascending perfection. This bequeathed us models of reality without qualitative difference, with a single hierarchy and a striving towards a singular end.

We can roughly summarize this model coming from the Greeks:

- We live in an unchanging and closed universe

- This universe contains two forms: the immaterial unchanging ideals and the mundane changing world of stuff

- Life operates by carrying out fixed ideal plans

- What matters most happens in ideas

- Matter is essentially passive and is given form from the outside

- Thinking happens inside the head

- Creativity is anthropocentric rather a fundamental feature of all reality

From this it should be clear that the Greeks held a fundamentally anti-novelty model of creation. This cannot be seen as a critique of the Greeks — the Greeks lived in a closed universe and developed practices that worked astonishingly well for that world.

But, we live in an open universe full of change — would it not behoove us to develop tools and techniques best suited to this world? If we, today, where to start from scratch to develop techniques for the production of novelty (creativity) can we honestly say that we would come up with models that paralleled the Greeks so closely? Perhaps our models of creativity would look far more similar to models developed in South and East Asia where creativity was a fundamental ontological aspect of all reality?

The West After the Greeks

As Christian theology developed it turned to the Greeks for key inspiration. Many of the key Greek concepts are transformed into Christian ones:

- God becomes the only true creator (following the Greek model).

- Poiein becomes creato — creation.

- The rules for all making (techne) become ars or what we would now call “art”. But not in the sense of the disciple of art — that emerges much later. “Art” in the Middle Ages simply meant skill. We can still see traces of this meaning in the phrases like “the art of cooking.” Ars covered all forms of making equally from building boats to painting an altarpiece (our contemporary art vs craft distinction required the invention of these two conceptual categories and disciplines in the 1700’s).

Umberto Eco in his critical history of aesthetics and ars/art in the Middle Ages sums it up this way, “this argument [referring to Aquina’s argument] shows how far the Medievals were from any conception of art as a creative force…” Then he goes on to quote St. Bonaventure “the human soul can make new compositions but it cannot make new things… “

The historian Camilla Nelson sums up the role of ars and the arts in the post Greek era (up to the 1700’s) thus: “For art was concerned with an entirely different aim — to know. Classical art aimed to produce the true… Originality was understood only in the sense of typicality — of art’s proximity to the great original… Once again, in the light of such aims originality and innovation as we understand them, not to mention the feelings of the artist and his artistic self-expression were entirely irrelevant.”

Again, it is important to say — of course we would now recognize what was done during this period was highly creative and innovative — but their self-understanding of their actions did not in any way involve the concepts of creativity and innovation. Their self-understanding of both what they were doing and what they should strive to do was to gain access to the ideals and copy. Michelangelo’s religious object making is a great example of this (as is his neoplatonic poetry). The strong muscular human bodies represented in the Sistine Chapel are not copies of actual bodies but copies of the ideal body.

What starts to change that leads to a new self understanding?

Arrangements of practices, habits, tools, concepts, regulations and environments changes such that new ways of being alive emerged in the 17 and 1800s. This new assemblage led to a new form of self — and ultimately the invention of the modern creative subject.

The Mind is Everything

The Greek two world model which gave rise to the model of a creative god who has all of the immaterial forms in his head shaped a model of the human. And by the 1600’s the model of the mind of god having direct access to immaterial truths becomes codified as a human model of possessing a mind (immaterial) separate from the body. This is most famously developed by Rene Descartes who said it most succinctly “I think therefore I am”. With the development of this model of the self a new form of subjectivity emerges:

- We are our ideas

- We do not engage with reality directly but through our internal representations of reality

- We are separate and different from our bodies and external reality

- We create our internal reality in a personal and unique manner

This “matrix” model of reality further pushes the western self understanding into a mental and disembodied realm. With “I think therefore I am” the world and our bodies become problems. All that is certain is that “I think”. Ideation becomes not just what we do — but who we are.

And this leads to a series of radical internalizations and essentializations of things that are best understood as being relational (everything gets put into the mind/brain). Creativity is a good contemporary example of this: it has become defined as a “thing” that can be found inside the mind/brain of a type of person “the creative” that can be best accessed by techniques like “brainstorming” or “lateral thinking“.

But, as has become clear, thinking does not work this way — it is not a purely internal phenomenon. The Cartesian model does not hold true, and it would be more accurate to say “we make therefore I am.”

The brain researcher Micheal Anderson says it best when describing how new ideas and abilities emerge: “We are [embodied] social environment-altering tool users. Tools give us new abilities, leading us to perceive new affordances, which can generate new environmental (and social) structures, which can, in turn, lead to the development of new skills and new tools, that through a process… of scaffolding greatly increases the reach and variety of our cognitive and behavioral capacities.”

Again, we need to ask: If things don’t work this way — if thinking does not work this way — would it not behoove us to develop tools and techniques best suited to how things actually happen? If we, today, where to start from scratch to develop techniques for the production of novelty (creativity) can we honestly say that we would come up with models that paralleled the Cartesian model? Can we honestly say that we would define creativity as development of novel ideas? We think not — and the Enactive Approach to cognition is showing us powerful alternatives.

Romanticism and the Birth of Creativity

With this new “Cartesian” subjectivity creativity — the development of the new emerges as a concept and a value. To be human is to make an internal reality. To be really alive is to be internally creative in a highly subjective manner. This is first developed/expressed in the emergence of the modern idea of art.

We see creativity in the sense of the human development of something new first emerging in the work of the pre-romantics and the romantics (starting roughly in the 1750’s). Here the stress on individuality and originality.

What is important is that the form this model of creativity takes is one that follows the Greek two world model. We internalize the heroic dematerialized world-removed god model of creation. And art and design are taught as the carrying out of the “god model” of creation: the heroic (male) creator imposes his vision on passive matter to transform it into the externalization of his imagination/ideas.

A Worldly Creativity Emerges

The heroic model of creativity is not the only one that emerges during this period. Here are a few of the emerging alternatives:

- Darwin and the emerging field of evolutionary theory (Kropotkin is critical here) articulate a vision or reality as creative without a first mover.

- Henri Bergson and William James relational philosophies of creativity.

- A N Whitehead develops a process based view of all reality with creativity as the principle process. He also coined the English word “creativity” in the first decades of the 20th century.

These and many other alternatives multiply over the century but they do not play a critical role in major trends in the early development of the field of creativity studies.

The Rise of American Individualism Gives Rise to Individual Creativity

The systematic study of creativity began after the Second World War. It developed within a Cartesian framework — with creativity being assumed to be a human psychological quality. It begins in the United States and is heavily funded by the US military and even the CIA (primarily in the arts). American heroic individualism is seen as a necessary and critical counter to Soviet collectivism. American heroic creativity is seen as a necessary thing to identify and cultivate to win the Cold War.

There is a type of ideological blindness that shapes the early development of creativity studies. It assumes that creativity is best studied and taught as:

- An individual human capacity

- It is something mental — in and of the brain

- It is a “thing”

In doing so much of the work in the sciences of evolution, ecology, systems and complexity is largely ignored. As is the work in other fields looking at the agency of things, systems, and relational processes.

A second key early lineage in the development of creativity as a field of study and practice is from the world of American advertising: Alex Osborn, an advertising executive played a pivotal role in developing the study and systematization of many techniques of creativity during the immediate post-war period (he is most famous for the technique of brainstorming). The most important of which is the Creative Problem Solving Process (CPS). What is important is that his approach, coming out of advertising, has all the biases that one would expect… (this will be the topic of another article).

Most importantly for this discussion — the Greek model of making and its historical legacies with its implicit assumptions remains at work.

Legacies, Patterns and Alternatives to Individualized Human Creativity

The study of creativity, in how it has implicitly carried forward Greek models of making, and with its focus on creativity being a thing associated with individual humans and their minds is highly problematic. There are six key issues:

- Creativity is not a thing, but an emergent relational process. It is not “in” something. The new emerges from a relational process. The totality of this relational process is creativity.

- Creativity is not about ideas. An idea is inherently tied to what is known and can be conceptualized. The new by definition will exceed and even defy current conceptualization. We need engaged experimental worldly practices to perturbate the new into becoming. Ideation works fine to stabilize and support the known, but the more central it is to a creative practice the more it leaves behind the possibility of radical novelty emerging.

- The psychological model of creativity has the wrong model of thinking. We now know that thinking is embodied, embedded, extended, enactive and affective (the enactive approach to cognition). Thinking is not an immaterial activity focused on purely internal representations and ideas. Thinking is embodied, uses and is changed by tools and environments. Thinking is a form of situated action/making. If you want to change how you think you need to change what you do — what you use and the environment you are in.

- It is wholly wrong to focus on the human — even for human creativity — environments, tools, collectives etc all play agential roles in the production of novelty.

- Creativity — the production of the new is all around us — and this is something that we can join. Creativity is not a human trait, but a worldly process that can be found everywhere.

- Creativity is ontological — it is involved in the making of wholly new and novel ways of being alive. This exceeds any narrow focus on utility. Creativity is a worldmaking practice.

We are our History

Our habits, practices, tools, concepts and environments all have a history and all shape us toward certain ends. We need to carefully disclose what is implicit and evaluate it critically from the perspective — what does it do? Who does it make us? Can we be otherwise?

We can see the implicit patterns of this history play out in how we approach creativity today. Many of the patterns that served the Greeks well to live in a closed cosmology do not serve us to live in an open dynamic and highly creative world.

We believe that our engagement with the processes of creativity are better served by putting down the habits, practices and tools of the historical Greco-West Asian traditions.

Isn’t it time we strongly and creatively shifted from this tradition?

We are not the first to suggest any of this — nor are we by any means the first to do any of this.

There are many many alternative traditions to draw up and many new paths open to us that will bring us into a deeper engagement with the beauty of creative processes and possibilities: other habits and worlds are possible…

Further Reading:

We are drawing upon our own readings and research into the topic over the last twenty-five years. We can recommend two good articles to start with: The Invention of Creativity: The Emergence of a Discourse by Camila Nelson, and Paul Oskar Kristeller’s Creativity and Tradition. Below is a longer list of sources:

On the Greeks:

- Plato Collected Works

- Aristotle Collected Works

- P Hadot The Veil of Isis

- JP Vernant Myth and Thought among the Greeks

- JP Vernant Myth and Society in Ancient Greece

- Diels Ancilla to The Pre-Socratic Philosophers

- A O Lovejoy The Great Chain of Being

On Art and the Middle Ages:

- Augustine Collected Works

- Aquinas Collected Works

- U Eco Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages

- G Duby Art and Society in the Middle Ages

- H Belting Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art

On Creativity:

- A Reckwitz The Invention of Creativity

- P O Kristeller Creativity and Tradition

- C Nelson The Invention of Creativity: The Emergence of a Discourse

.jpg)