WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 226! Enacting a Creativity Manifesto...

Good Morning transient individuations of the pull of a waning moon.

This week we are writing from the edges of two conjoined oceans: the north-east edge of the Pacific and the north-west edge of the Atlantic. Words, winds, waves, and currents breathing in an out with the moon across differing shores.

As the Gregorian year begins we have been thinking a lot about beginnings.

But beginnings are complicated.

With creativity, there is never a beginning in the sense of a clear rupture. There is no electric a-ha visionary moment that can be said to decisively mark the beginning of the development of the new. Of course, there are many moments and flashes of insight in creative processes – but they are never the origin, cause, or independent from all of the other ongoing, widely distributed and deeply entangled practices, experiments, and collaborative actions.

While we might long for the neat, the clear, and the obvious – there is never a neat beginning – and everything that appears as the markers of a beginning – those happen much later. And most often, the purported beginning is recognized (invented) in hindsight to fit the appropriate tropes of telling heroic creativity narratives. In this regard, it is fascinating to contrast Brian Merchant’s complex, distributed account of the development of the iPhone with Walter Iscason’s heroic individualistic portrayal of the same story.

Change and creativity are everywhere and everywhere ongoing. And as we enter this stream, we have never left to deliberately “begin” a creative project, we become less like heroic originators and more the “helpmates” to creativity's own emergence (here we are paraphrasing Brian Massumi).

This is why we like to stress that everything – including beginnings – happen in the middle. Creative Middle-Beginnings.

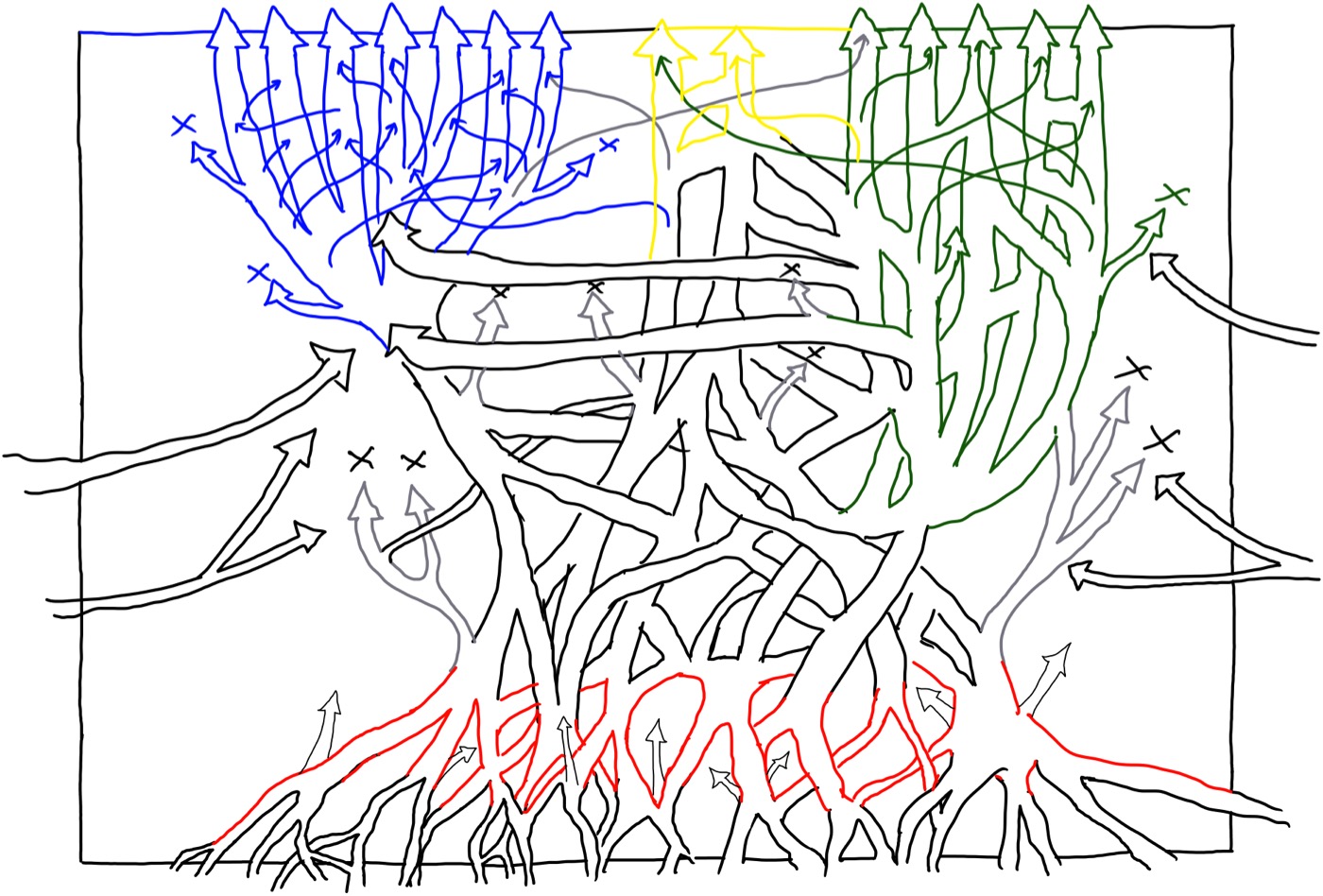

Differences that are new – novelty – emerge from the middle of a dense thicket of ongoing relational processes. They emerge where new practices lead to new transversal connections, new relevances/affordances, and new emergent propensities:

Over the fall and winter of 2025, we wrote about this question of creative beginnings that are of the middle with three series of newsletters:

So, with fifteen newsletters on the question of beginnings and what comes before beginnings – it is fair to say that we have been thinking a lot about beginnings as we come into the new year!

NOTE: If you are curious about going back into these series – a good place to start is Volume 222 where we developed a set of experimental definitions for a series of key concepts from this set of newsletters (transjective, transversal thicket, rhizome, collaborator, and temporary autonomous zones etc.).

Because engagements with creative processes have no beginning in the manner that has been imagined by the classical logics of a hyper-individualized brain-centered approach to creativity (those lightbulbs flashing deep in the brain of the would-be genius), there is a real need to carefully and appropriately mark these pre-beginnings and middle-beginnings – with their odd, vague phases and transitions.

From the perspective of creativity, we are always at all times both in the middle and at a potential beginning of the emergence of some novel qualitative difference. It is as Gottfried Leibniz noted, “I thought I had reached port, but I found myself thrown back into the ocean.”

The radical potentiality of such a situation can be enormously energizing, and the ambiguity of such a situation can equally be cripplingly paralyzing. This is where we find that rituals and artifacts can be very helpful.

Rituals are formal collective practices that participate in producing a meaningful transition of states. They are a deliberate form of caring for the activity of crossing a qualitative threshold (see Vol 137.). These qualitative thresholds have always been ritually marked by cultural practices: think of coming of age ceremonies, marriages, membership rituals, funerals, etc… Even yearly birthdays and New Year's celebrations are rituals of nebulous qualitative threshold crossing.

Why do we say nebulous? Obviously, you do not transition from child to adult all of a sudden, nor are you literally one year older overnight, and perhaps you have been living for decades with your significant other before you decide to get married, so it is never clear when one thing ends, and another begins. But the ritual is very constructive in both marking a moment and creatively facilitating the qualitative threshold crossing: you are no longer this… You are now that…

Creative processes are full of qualitative threshold crossings – and the issue is that these most often will pass unnoticed. This is one of the great challenges of a creative practice: we most often do not – and cannot realize that we have crossed a qualitative threshold and are doing something qualitatively different. Think of our example, from evolution, of the creative qualitative transition from dinosaur to bird. The event of the first dinosaur to fall out of a tree and not die was insignificant in the moment. It was only millions of years later that, as flight fully emerged as a qualitatively different mode of being alive, this early moment gained significance. How else could it be?

The realization (and actuality) of what is a meaningful difference emerges late in the process. The examples of this form of blindness are endless – Steve Jobs thought that he had invented a perfect minimalist mobile phone, and he hated the idea of an app store. That Apple (and many many others) had participated in the early phases of collectively inventing a qualitatively new mode of being alive was invisible to most at the time. The early philosopher of creativity, Alfred North Whitehead, famously said of the new, “We make it do the work of the old.”

Far too often, we frame the potentially qualitatively new in terms of the old – and, more specifically, in terms of the improvements of the old: “it's just a better, faster, easier version of …”.

This is why we love using the phrase “Keep Difference Alive” in a talismanic manner. This phrase, when understood from a creative perspective, can act like an artifact – a talisman to protect the new.

“Keep Difference Alive” is a reminder that, (1) the new must be made, (2) it involves the production of a “difference that makes a difference” (Gregory Bateson’s wonderful phrase), and that (3) we are forever turning it back into the known – the old (as Whitehead noted) – the given and in the process losing the new to the old (see Volume 181: The Yeah Yeah Yeahs).

In some of our workshops, we will mark critical moments of transition with various actions and artifacts. One artifact we will use is a sticker of the “Keep Your Difference Alive”:

And at other times, we will hand out this image as a larger poster. We are big believers in artifacts that can act as prompts, catalysts, reminders, and relays for further actions and practices. (If you didn’t already do this, you can download this poster and the Yeah, Yeah, Yeah’s manifesto).

We are all in need of talismans and rituals that protect, not us, but creativity, novelty, and difference itself!

Because of this, we have other tools and rituals to mark important transitions – perhaps you have developed some of your own? We would be curious to hear about these (please drop us an email if you wish to share your tools and rituals to protect the emergence of the qualitatively new).

When we are working with organizations on larger creative projects, one of the rituals we use to help keep emerging differences alive and thriving involves collectively developing phase-relevant manifestos:

Early on, we will develop a general “Orienting Manifesto.” And later in the project, as novel differences emerge, we will develop an“Internal Manifesto”. This kind of manifesto is not for a general audience – a public – rather it is a tool to help keep the focus on the new and different that is emerging.

The developing and writing of a manifesto is an important ritual and produces a critical artifact.

These days, manifestos get a bad name – and for the most part, rightly so. We are continuously confronted with either the preposterous and disingenuous ones that monopolistic organizations develop – think of the absurdities of Google's “do no harm” manifesto – or from the likes of the Unabomber…

Historically, manifestos have always been a mixed bag – there is perhaps an equal number of fascistic manifesto’s (the Futurist Manifesto or Project 2025) – as well as progressive writings (e.g., the writings of the Luddites, early feminists, anarchists, and many experimental artists).

For us, this prophetic, aspirational, and experimentally guiding form can be employed strategically to great effect in creative circumstances to push experiments towards novel horizons and keep difference alive.

And it is this aspect – how the collective writing and deployment of a manifesto can help keep a novel difference alive that interests us the most. One powerful aspect of the manifesto in regards to creativity is its ability to work as a form of experimental blocking – to say no – to refuse certain practices, paradigms, and logics. And this ability to ritually, collectively, and publicly articulate what will not be done is critical (see Vol 210 for more.).

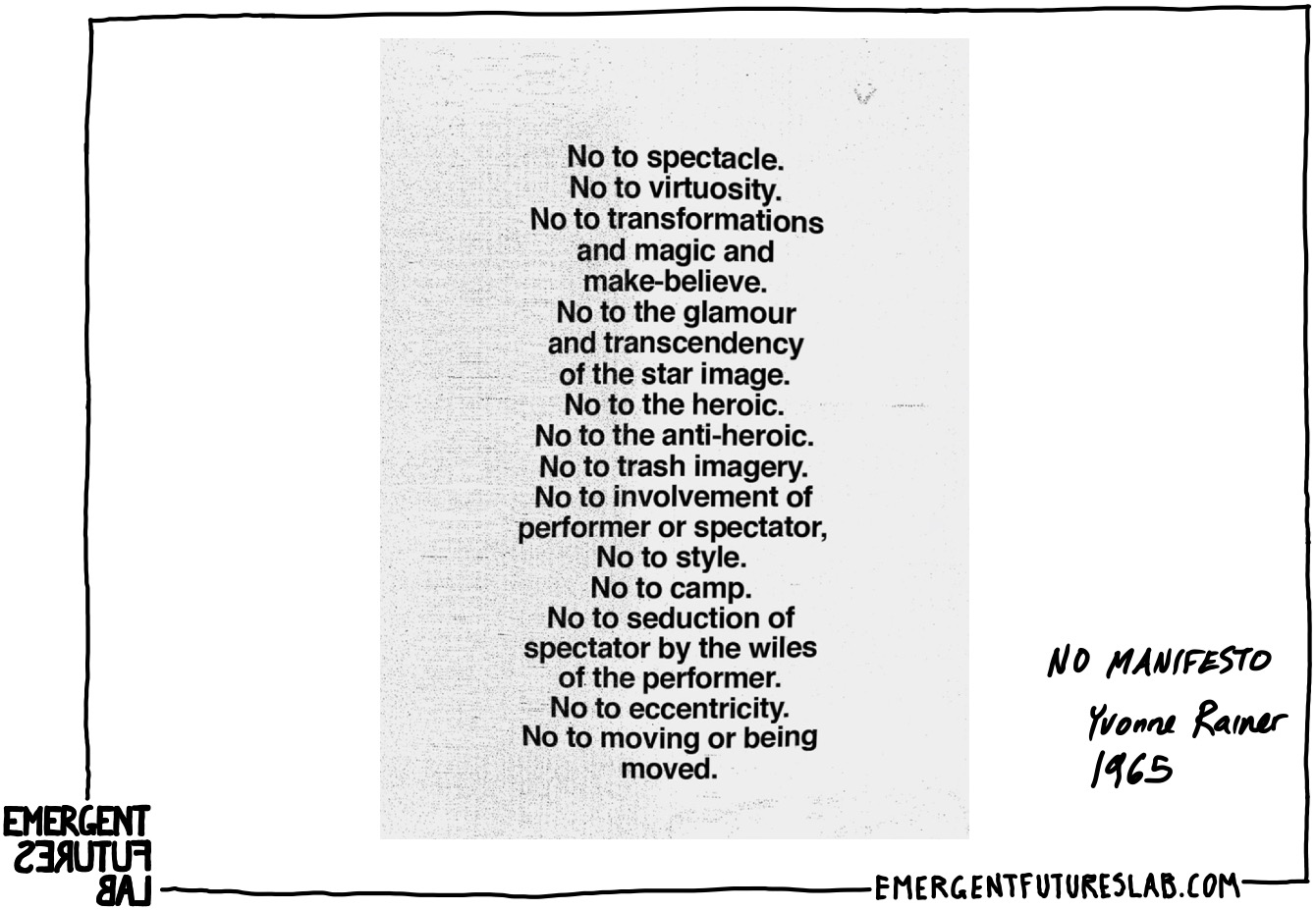

One of our favorite examples of this form of a manifesto is Yvonne Rainer's No Manifesto.

Yvonne Rainer (b 1934) is an important figure in the worlds of dance, cinema, and the arts more broadly. They began studying modern dance in 1957, eventually studying with Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham. By the early 1960’s, she was part of an experimental cohort of artists, musicians, philosophers, activists, and dancers challenging the contemporary paradigms of the arts. And it is in response to the ethos of classical dance and its ideas of performance, she wrote the No Manifesto as a powerful refusal to continue with the old:

It is what we would consider to be a paradigmatic example of an “Internal Manifesto” – it is there to orient her work, that of other choreographers, and dancers primarily, and audiences only secondarily. It is written to keep an emerging qualitative difference alive.

This was written in conjunction with her creating an astonishing series of dances that focused on the capacities of the body, everyday actions, and chance – and not plot, representation, expression, or communication, which was taken for granted by so much of the historical art traditions (The most famous of these works is the astonishing Trio A). And it was equally written to foster a movement and publicly mark a transition – serving as a polemic, a guide, a rallying point and a talisman all at once.

Even today, it makes for astonishing reading – take a moment to read this Manifesto aloud. The thirteen no’s are propulsive in their refusal and challenge to do something different. The equal strength of belief in novel possibilities and adamant refusal to fall back into the known is bracing, and euphoric in its openness – “I thought I had reached port, but I found myself thrown back into the ocean!”

Rainer went on to make an important body of dances, then turned away from dance for about twenty years – making an equally important body of films – and then, late in life, returned to dance (all of which is worth an extended deep dive into).

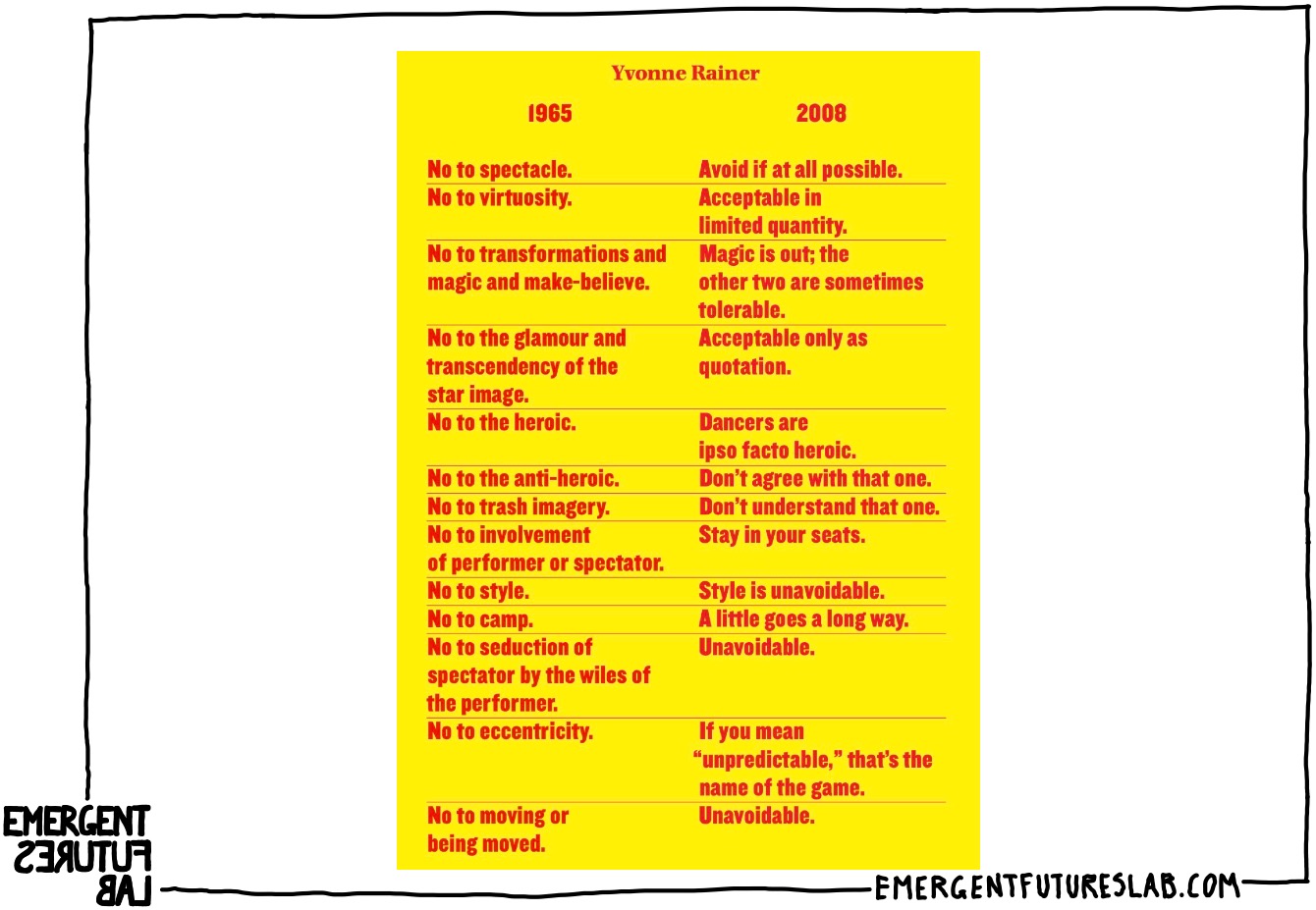

During her return to dance in the early 2000’s, she also returned to reflect on her 1965 No Manifesto. Their 2008 version is a very interesting mix, staying true to many of the general principles, but acknowledging the complex reality of trying to move in this alternative direction (“Avoid if at all possible”) – and realizing that she has changed her mind about others (“Don’t agree with that one”):

It is wonderful how she reflects on what she wrote and critically and creatively rethinks her practice for a new historical context. And that is the thing with Manifestos – they are not forever – they are context specific – they are tools to be used in a certain context – a certain process of creative threshold production and crossing. Like everything with creative experiments – we don’t have to agree with them or even continue them…

This gets at two critical aspects of creative manifestos: they involve rules, and they will change. Creativity and so-called “creatives” are so often positioned in an absolute opposition to rules – too often creativity is still defined as a practice that involves “breaking all the rules,” and living beyond all rules…

But this is a fundamental misunderstanding of the creative and generative logic of limits (what we prefer to call configurations or constraints). Limits are productive, and new limits (rules) produce new fields of possibility. One only needs to think of games such as chess. What makes the total space of possibilities in chess possible? It is the limits of a set of pieces, a limited field of play, and a limited set of actions possible by each piece. Rules act to both keep differences alive (block a return to the old), and are generative of a field of novel possibilities that far exceed the known – or even knowable.

This leads us towards another important type of creativity manifesto: the Orienting Manifesto. Often, when we begin a project, we will start by collectively developing a manifesto about the forms of creativity and practice that we aspire to orient ourselves towards as a direction or vector. While the Internal Manifesto marks a later emergent transition (when novel differences that can make a difference start to emerge), the Orienting Manifesto is part of ritual practices that mark the beginning of the preparations in advance of the “beginning” of a project.

Thus, Orienting Manifestos are usually very general and speak to the preconditions for a creative practice in general.

One of the most interesting examples from the same period as Yvonne Rainer's No Manifesto is The Immaculate Heart College Art Department Rules written by the artist, activist, and Sister Mary Corita (Corita Kent 1918-1986) and her students at the College in the early 1960’s:

Again, these are worth pausing to read aloud:

“RULE 1: FIND A PLACE TO TRUST AND THEN TRY TRUSTING IT FOR A WHILE”

“RULE 4: CONSIDER EVERYTHING AN EXPERIMENT”

“RULE 6: NOTHING IS A MISTAKE. THERE’S NO WIN AND NO FAIL. THERE’S ONLY MAKE”

“RULE 7: THE ONLY RULE IS WORK. IF YOU WORK IT WILL LEAD TO SOMETHING…”

Again, take some time to reflect on each in one's own way. We like to treat these as prompts for discussion or reflective writing. On the website dedicated to her work, there is a great page on this highly influential manifesto where former students and artists reflect on individual rules and what they meant to them:

This set of “Art Department Rules” were most famously adopted by John Cage for his class on experimental composition at the New School for Social Research (NYC) from 1956 to 1961 where he and his students went on to have an enormous impact on the contemporary arts and cultures of the era (Yvonne Rainer was a key member of this milieu, as was our dear friend Alison Knowles - see Vol 217). Cage importantly and interestingly makes two changes: first, he underlines “Nothing is a Mistake” and then in the rule that quotes him – rule number ten. When he changes “quantities” into “qualities”:

RULE TEN: WE ARE BREAKING ALL THE RULES. EVEN OUR OWN RULES. HOW DO WE DO THAT? LEAVE PLENTY OF ROOM FOR X QUALITIES.”

And this is something so critical to all practices – leaving space for the emergence of novel, unknowable, and non-existent qualities.

A look at important popular versions of Orienting Manifestos for joining creative processes would not be complete without Bruce Mau’s An Incomplete Manifesto for Growth. Again, here we find a series of pithy statements supported by short explanations. Mau begins with one of the most critical insights for a creative practice:

Allow Events to Change You…

Too often in the classical model of creativity, it's seen as something someone does. It is an outward act imposed upon passive matter by an almost god-like being, who most certainly does not change. Mau’s important first rule does away with this nonsense – things will change you – deliberately allow them to…

“We want…”

Another key critical form of manifesto that emerges from a creative practice is the public-facing manifesto. These are often what we most commonly recognize as “Manifestos.” The greatest of all classical manifestos, The Communist Manifesto, is a profound example of this. But for our purposes of using a manifesto as a collective project that can also act as a talisman to keep difference alive, The Communist Manifesto is a different creature – a long prophetic and polemic argument to move towards an already defined state.

That said, the powerful scope of the Public Manifesto is often best seen in the world-making challenges of political manifestos. In 1966, the Black Panther Party issued a powerful, precise, and succinct political ten-point manifesto. It is interesting to put the previous two manifestos of the 1960’s art world into dialogue with this 1966 manifesto of the astonishly far reaching ecological creativity.

Again, this manifesto is worth reading aloud, discussing, and meditating upon. Each of the ten begins with a direct demand: “We want… !”

In our online community of creative practice, WorldMakers, we have collective weekly creativity exercises. These range from the very simple to the elaborate. And at the end of the year, Andrew challenged the community with an exercise to Write Your Own Creativity Manifesto.

And now our hope is that reading these various examples gets you excited to develop your own collective manifesto and to use differing forms of manifestos – and a collective practice of their writing – as a ritualized aspect of your collective creative practice.

Here is our prompt to get you started:

Periodically, in an attempt to experimentally gather, coalesce, and push the emerging qualitative difference of a project across a threshold, a manifesto becomes an internal necessity.

Manifestos are powerful little tools for not only making a claim, but also as catalysts for action.

For doing. For making. For probing. For experimenting.

We invite you to consider the manifesto as a tool within the ongoing and everywhere task of creativity, not as a fixed statement of beliefs, but as a talismanic map to push possibility and potential while refusing the given. What would such a Manifesto of Creative Difference look like for you?

Try this either on your own, or if possible, work with others (you could start by contributing one or two lines to a co-shaped Manifesto of Difference that your community builds together). It does not need to be long – ten to fifteen points seems ideal. And remember – as Yvone Rainer demonstrates: it is an ongoing and changing document for the community to reference and shape – it is never a fixed stone tablet to be worshiped for all eternity.

Again, if you feel so compelled, we would love to read what you have developed – please share these with us.

Well, that is it from us for the week.

We are excited about next week. Next week, we will share An Orienting Manifesto for Creative Processes that we have been developing over the last couple of years – we are excited to see what you think!

So, as we begin the new Gregorian Year – let's experiment with rituals to mark the creative middle-beginnings of novel qualitative difference.

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Loving this content? Desiring more? Apply to become a member of our online community → WorldMakers.