WorldMakers

Courses

Resources

Newsletter

Welcome to Emerging Futures -- Volume 228! Experiments and Manifestos...

Good Morning experiments in their own becoming un-repeatable,

This week, Jason and I are back at the University. It is our first week back running the Innovation Lab and teaching a new cohort (Andrew is already deep into things with his students). In my upper-level class on innovation and design, I am beginning by getting them to make anything (following the logic “Begin Anywhere” from last week’s manifesto) – while stressing that what matters is that they are experimental.

I really want them to make more than they can imagine – and use everything they make experimentally. But what do I mean when I say “experiment”?

There is nothing magic, complex, or occult by what I mean by “make experimentally” – all it is, is to ask and answer repeatedly and in new contexts,

“What else can it do?”

This should not be an abstract question that can be answered via observation and discussion. Of course, we can have a hunch or speculate on what it might do – but the really interesting things only begin to happen after it is made – when we begin to use these things in new ways in new contexts.

The key to this experimental ethos of design is to make things and then get these things to do things that are not expected. Importantly, one cannot stop after one test – we need to keep pushing things – to follow a branching line of flight towards emergent thresholds (we wrote about this in detail in Volume 213 in our series on Blocking).

But the challenge with my design students is that this is a form of experimentation that they really do not understand whatsoever. But, it's not that they do not consider themselves to be good experimenters and makers. They do. When I ask them if they experiment, their answer is an unequivocal:

Yes! We appreciate and do experiments all the time. My whole practice is experimental.

And they are right about this – everything they do is experimental. The problem is that what they understand by the term experiment is completely different from what we mean. When asked: What is an experiment? – The common answer is that it is a “test”: “We are trying to figure out if it works”.

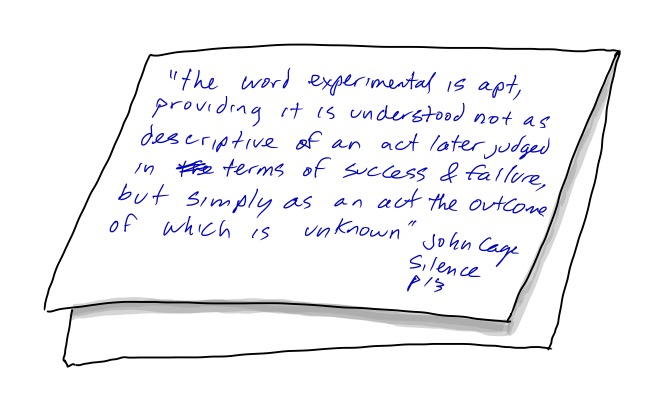

And this is something totally different. For us, experimentation has always meant something like how the experimental composer John Cage articulated it:

“The word experimental is apt, providing it is understood not as descriptive of an act later judged in terms of success and failure, but simply as an act the outcome of which is unknown.”

And this is exactly the opposite of my students – for them, an experiment is a test where they are looking to see what succeeds and what fails.

Why is it that we are approaching experimentation in a creative practice so differently?

One important insight came earlier this week after we published the newsletter. In the last newsletter, we included a “Manifesto for a New Creativity” – it was composed of thirteen points. In one of the points, “Leave Space for the Unexpected to Sweep you Elsewhere,” we quoted John Cage saying (in our paraphrase):

“It is only an experiment if we do not know the outcome”.

Now that the Newsletter shows up directly in our online community of creative practice (WorldMakers), we can have an embedded ongoing discussion. The very first comment that the newsletter received was from Florian Rustler, a German Creativity Consultant who is a long-time participant in World-Makers:

“A lot of inspiring content in this volume.

I want to focus on one for a start that resonated a lot with me as it relates to a recent experience with a customer. “John Cage famously said, “It is only an experiment if we do not know the outcome…” At the client organization my contacts were talking about how to ensure that the “experiment” - they use that word - leads to the desired outcome. I then had an interesting conversation with them about the whole point of the experiment being that we don’t push for a desired outcome. That way of thinking however is at odds with the culture of the organization. So we will have future conversations to make this easier for them”

I was thinking about this comment all week – especially in regards to our students who had a very similar approach to Florian’s clients. They are both hoping for a successful result or a desired outcome.

It had me wondering about where most of us are first exposed to experiments and the logic of experiments. And it seems that for many of us, it is in our elementary schooling where an exploration of experimentation shows up in the context of the sciences. While within the sciences themselves, there are many, many differing forms of experiments, and in the literature on how the sciences work, there is a very rich debate around the roles and logics of all these forms of experimentation – this does not seem to be the case in our schooling. In our public discourse of the sciences, there is really one overarching idea of what an experiment is and how it functions. The most common scientific use of the term experiment in popular culture and schooling comes from Karl Popper and his 1935 book The Logic of Scientific Discovery. In it, Popper made the claim that science advances primarily by the use of experiments to prove or disprove a hypothesis. Hypotheses are proposed and then tested via an experiment with the hope that it succeeds, but eventually most hypotheses are refuted.

While this vision of “how science works” was quickly proven wrong both pragmatically and theoretically, in popular culture (and especially in our education system), the concept stuck. Now our culture most broadly understands the purpose of a scientific experiment – and of experimentation more broadly as:

The goal of an experiment is to test a hypothesis in a controlled setting. And how do we “test” a hypothesis? By trying to disprove it.

[NOTE: If you are interested in these debates, here are a couple of useful starting points: Isabelle Stengers: The Invention of Modern Science, and Ian Hacking’s Representing and Intervening: Introductory topics in the philosophy of natural science].

This realization made me aware that for Florian’s clients and our students, of course, they would want an experiment to have a desired outcome – because experiments, when understood from Popper’s perspective, can only have one of two outcomes – true or false. And who wouldn’t want their experiment to result in a positive outcome?

Cage’s approach to experimentation is not the common one – rather, Popper’s is. Experimentation, it seems, lives quite successfully in two very different worlds…

The challenge for Popper’s vision of experimentation as hypothesis testing is that it is of limited use in both the sciences and especially in creative practices.

His view of experimentation in the sciences is a profoundly top-down image: it pictures scientists as theorists sitting around and rationally developing explanations which they then have their team test for validity. But little of what really happens in the sciences works in such a manner. A view of the sciences or creativity as operating primarily via falsifiability cannot account for all of the experiments that are fueled by exploring odd observations, strange occurrences, and practical acts of making. Ian Hacking, in one of our favorite books on scientific experiments, makes two critical points about the complexity and difficulty in experimenting in a section aptly titled: Experiments Don’t Work:

“Most experiments don’t work most of the time. To ignore this fact is to forget what experimentation is doing. To experiment is to create, produce, refine, and stabilize phenomena... But phenomena are hard to produce in any stable way. That is why I spoke of creating and not merely discovering phenomena. That is a long hard task. Or rather there are endless different tasks... Perhaps the real knack is getting to know when the experiment is working. That is one reason why observation, in the philosophy of science usage of the term, plays a relatively small role in experimental science. Noting and reporting readings of dials… is nothing.”

(Ian Hacking, Representing and Intervening)

This paragraph and Hacking’s whole discussion of the actual forms experiments take in the natural sciences is really insightful for creative experimental practices. Afterall he is talking about how the practices of scientific experimentation are creative practices. As he puts it so astonishingly: “an experiment creates, produces and refines and stabilizes phenomena…”

Here, it is important that we begin by properly understanding what Hacking means by “phenomena”. A phenomena, for Hacking (who is using the term as it is used in Physics, not Phenomenology), is something that has six qualities: it appears, is discernible, has a regularity, is relevant, noteworthy, and has effects. In our terms, it is a transjective (or an affordance). A difference that makes a difference.

To understand this logic of what it is to create phenomena, it is worth taking a brief detour into how we introduced the synonymous term “transjective”in Volume 221:

“What is relevant to an organism in its environment is never an entirely subjective or objective feature. Instead, it is transjective, arising through the interaction of the agent with the world. In other words, the organism enacts, and thereby brings forth, its own world of meaning and value.” (Jaeger et al)

And we continued with this example:

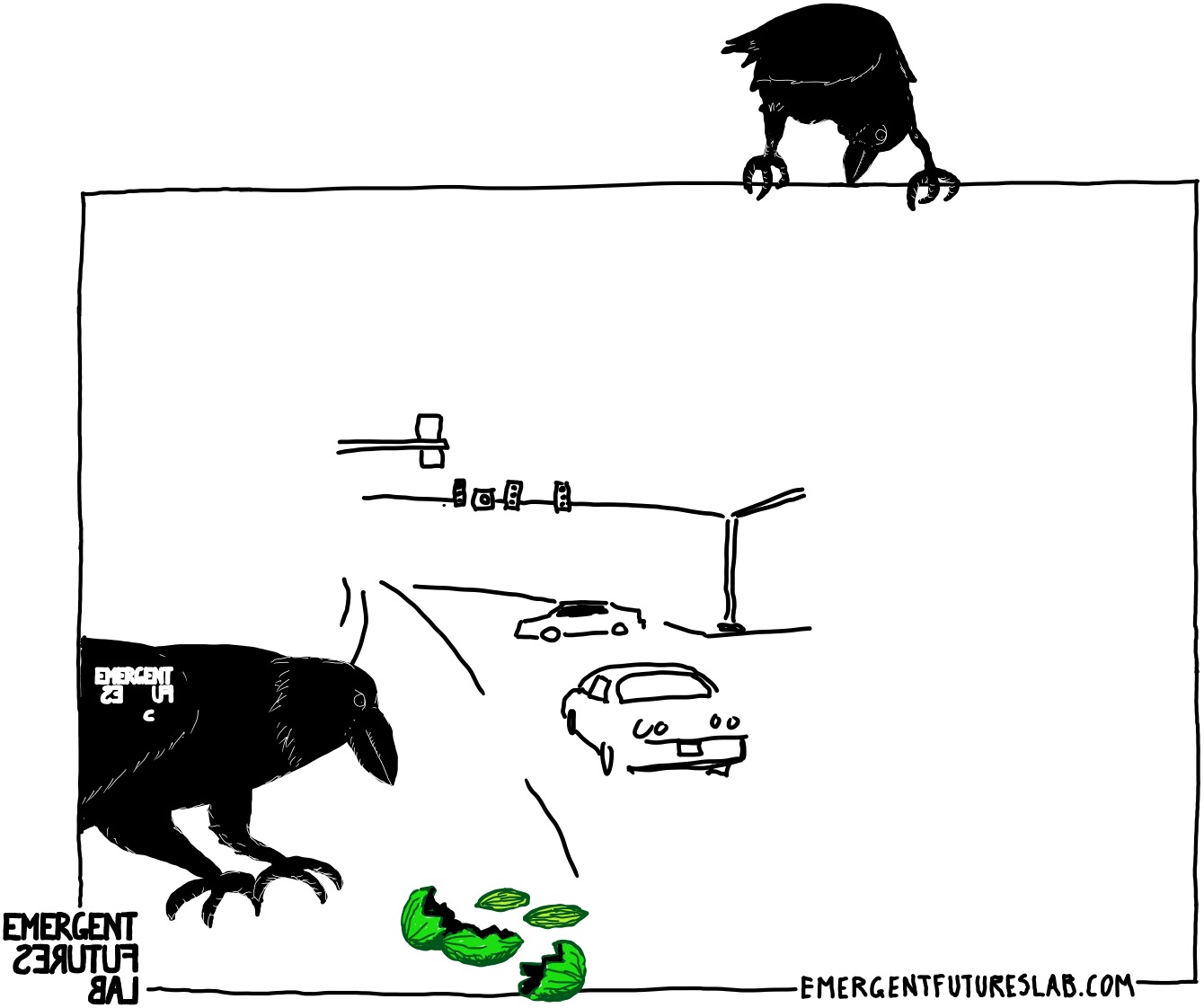

“If you think about the crow story – our favorite one – where they are using an intersection with a traffic light and cars to crack nuts. The reason that we humans do not see the intersection as affording nut-cracking possibilities is because, it’s not relevant to us.

“Active practices make things emerge for us as relevant – as “phenomena”. This happens because we are precarious, specifically embodied beings that always find ourselves in a concrete environment with some general active concern. For example, when we are biking down the street, now that crack, bump, or pothole shows up as relevant and significant in a new and very real manner (but when we were driving on the same street, they never came forth as phenomena).

“This is equally true for the crow. When they have a nut in their beaks, the world looks and feels different. Now the car shows up as relevant in a new way. Now the traffic lights show up in a new and relevant manner. The crows are experimentally creating and stabilizing things as things (phenomena).

“Relevance is created and realized by our exploratory actions in a context. Relevance is not something objective or subjective or pre-given. It comes into being via our embedded actions. Relevance – and from it, meaning – and from this, knowledge – is all a transjective creation of an engagement.

So a creative experiment involves not so much the proving or disproving of something, but the very creation of a new relevant stable phenomenon and effect (what can also be termed an affordance – a relational opportunity for action).

But what is fascinating is that all of this is not even Hacking’s main point. His main point is that the real key to carrying out a successful creative experiment first involves the very difficult skill of:

“getting to know when the experiment is working.”

What does it mean to “get to know when an experiment is working or not”?

How hard can this be?

Can’t we tell quite easily when something is working or not? We know, for example, if our car is working, it turns on. And this is pretty much true of most things… But – Clearly it can’t be that easy, or he would never have brought it up…

Have you ever watched “The Great British Bake Off”? (in the US and Canada, it is called “The Great British Baking Show”). It is an eccentric and humorous baking contest to find the best British amateur baker. This happens through a series of elimination contests over 12 weeks. Every week, one of the challenges the bakers face is the “technical challenge.” This is a type of mystery challenge that is just sprung on the bakers without any opportunity for them to prepare or practice:

“Paul and Prue would like you to make ten identical French cream horns…”

And it is only then that they first see a set of unmeasured ingredients and are given a very cursory recipe – that might start something like this:

“Make the French horns…”

There will be no further details or measurements – just “make the French horns… You have two hours…”

What is fascinating in watching the show is that every week, some of these accomplished bakers will not know how to make whatever is being asked of them (the French horns, for example). But they do try to experiment and make something as best they can. And at each critical moment of their bake, say when things have been baking in the oven for some time, they will, while looking intently at their bakes, and say something like:

“I just don’t know what I am looking for!”

They do not know if their experiment is working… That moment in the Technical Challenge is a great example of the painful apprenticeship in learning how to know if the experiment is working.

And the more experimental and open the experiment is, the less it is possible to know if it is working. This is the case in any creative experiment: we must begin it before we know what we are looking for… We don’t even know how to evaluate if the experiment is working or not – never mind if it is “successful” or not!

But this – the knowing of how to judge success or failure- is precisely what needs to be known in advance to carry out a “test” – we need to know before we begin how to evaluate success or failure.

Let’s consider another, more creative example: Parkour – the practice of “building running” (if you are unfamiliar with this wonderful activity, it is worth watching a few videos starting with the previous link). Say a group of Parkour participants is standing at the top of an odd stairway for the first time. What is relevant to their movements in a stairway would not be known. Why? They want to experimentally find a new way to move down the stairs, and so what will show up as the phenomena (affordances) of the stairway is going to need to be experimentally enacted – it is not already there (no part of the stair is its identity or normally proscribed purpose).

In normal life, the phenomena of the “hand rail” has been so well enacted that it shows up as something “objective” – we take it as reality. We simply grab with our hand to assist our balance in going up or down the stairs. In Parkour, the experiment is to actively ask: “What else can we bring into existence with this space – with this handrail?” The given is returned to zero… and we must co-create a new given – but because we are doing this, we cannot even know if any thing is, at first, “working”...

It will be a slow, hesitant, indirect, surprising, and iterative process by which the participants will come to co-create an experiment that is “working” as they become skilled at intervening in this world of the staircase so that new phenomena and effects come to actually matter.

In short, it is only when we come to see/sense things differently – when new phenomena show up as relevant, stabilize and participate in new effects – when things become sensed as the new “normal” – that an experiment works – and we can begin to take it on fully (this video provides a great Parkour example).

The question “Is it working?” is itself an experimental hands-on question. The early phases of a creative experiment involve an apprenticeship in forms of conjoined making and doing such that one becomes correctly sensitive and attuned in the embodied ways of know-how.

Seeing and sensing experimentally is a paradoxical art that requires, with every new experiment, a new apprenticeship. Paradoxical because it puts us in a chicken-and-egg situation – what comes first? Noticing? Speculating? Sensing? or Acting?

What cuts through the paradox is action – and an understanding that seeing and sensing are themselves skillful actions. Seeing and sensing are always already forms of doing. Noticing, observing, and sensing the odd, different, and unique as the odd, different, unique, and worth following happens because we begin an apprenticeship in learning to act differently.

But precisely because we need to first learn how to even sense if something is working, we rarely observe the odd as odd. And this is especially true if we are acting as smart, capable, effective, and efficient beings (e.g., good students or good business professionals). For them, the odd is most often irrelevant, stupid, and not useful – or simply – and this is perhaps the most common circumstance: fully visible – but as simply a flawed version of the known. It is ironically easily recognized – the odd is not something that leads towards the new, but is rather a clear sign that the experiment failed and we should move on.

Thus, what is critical for creativity is that we move away from the practices that have traditionally come to culturally define experimentation: The over reliance on the top-down logic of the hypothesis disproving experimentation. It is logical that we find everywhere ideas take the lead. In creative contexts, experimentation also imagines “theorists” – creatives, executives, and leaders of differing divisions gathering in a boardroom to develop the ideas that they will then delegate to others to “test”. And of course, as Florian noted, they will want these experiments to yield their desired positive outcome.

Now, there is nothing wrong with hypothesis testing – it is a useful practice in the right (but highly limited) contexts. The problem, in relation to creative practices, is that it is fundamentally anti-creative (it is about the known – all we do not know is if it will work).

A creative experiment is, as we said last week, only a creative experiment if “This is equally true for the crow. When they have a nut in their beaks, the world looks and feels different. Now the car shows up as relevant in a new way. Now the traffic lights show up in a new and relevant manner. The crows are experimentally creating and stabilizing things as things (phenomena).. But this, by itself, is as we now see – neither quite correct nor quite complete.

And here we need to rethink our manifesto from last week: It is not quite correct because it stressed “not knowing” – while the new will, in actuality, will be “non-existent". And it is not quite complete because it fails to consider the apprenticeship that begins before one even knows if the experiment works…

So our question for you, our dear readers, his how should we revise this statement:

“It is only an experiment if we do not know the outcome.”?

How should we account for the necessary wandering in the wilderness, not knowing what it might mean for the experiment to “work”?

Next week, we will share some of our experiments on this question.

Till then, experiment in ways to stay warm (we are expecting a huge snow storm), and keep difference differing!

Keep Your Difference Alive!

Jason, Andrew, and Iain

Emergent Futures Lab

+++

P.S.: Wish you could comment and engage directly with these ideas? A Newsletter + subscription brings you into the conversation—add your voice here.

P.P.S.: Want to go further? WorldMakers brings you weekly exercises, live events, our evolving bibliography, our live event archive, and a community exploring these ideas together. Join us here.